Wise cracks

TDC

Kevin Cameron

I DON'T KNOW ABOUT YOU, BUT ALL MY life I've had it drummed into me that forged parts are the coolest-strong and most durable-while cast parts are weak and full of defects. Parts machined from plate or billet, the story goes, lie somewhere in between.

For example, high-duty crankshafts, such as used in racing or aircraft en gines, are invariably forged, while hum. drum production stuff is cast. Racing chassis are made from extruded or fabbed-from-sheet sidebeams, with ma chined-from-solid steering heads and uprights, while production chassis have (ugh, patooie) cast heads and uprights.

It used to be true, but times have changed. Get ready for high-strength, high-durability cast chassis. Here's why the old story was true-when it was true:

Many years ago, an Englishman named A.A. Griffith got to wondering why real materials are as weak as they are. Even in the 1920s, it was possible to calculate, from basic physics, what the strength of glass ought to be. Griffith wanted to know why the actual strength is only one percent or less of the theoret ical strength. He began to consider how this could be. He concluded that real materials must be in some sense discon tinuous; that is, they contain defects that weaken them-cracks or voids.

The gist of Griffith's discovery was that defects below a certain size will remain passive under stress, while those above this size will enlarge and grow into actual cracks. Under contin ued stress, these propagating cracks would lead to failure, causing the part to fail at a very low stress level. In the case of the glass rods that Griffith used to test his ideas, the defects were sub microscopic surface scratches. When great care was taken in drawing ultra fine glass filaments with zero surface defects, the result was enormous strength-closely approaching the cal culated theoretical strength. Today, fine, defect-free crystalline filaments such as carbon or boron fibers are the basis of super-strength composites.

Griffith defects are part of the reason why castings have been associated with inferior strength, while forged material behaves better. Molten metal readily absorbs gases and, if steps are not taken to de-gas the melt before pouring a casting, this gas comes back out of solution as the part cools, forming bub bles or voids in the metal. When these voids exceed the "Griffith crack dimen sion," they will propagate under stress to form cracks that result in low strength. Today, in some cases the metal is degassed chemically, by adding material that combines with the gas to form an insoluble slag. The slag can be removed before pouring the metal. In other processes, vacuum may be ap plied to extract the dissolved gases. -

Conversely, part of the value of forg ing is that the act of subjecting the part to the pressure between the forging dies is purely mechanical-it physically closes up voids, making them smaller than the Griffith crack dimension. A similar idea, now being applied to cast ings to improve their fatigue strength, is called Hot Isostatic Pressing, or HIP ing. Fresh castings, rife with defects, are placed in a pressure chamber at a high but non-melting temperature. A pressure of 15,000 psi or more is then applied, which closes up internal voids much as if the part were forged.

The strength of metals can be im proved by alloying-adding percentages of other materials. In some cases, atoms of different sizes can act as keys to pre vent one crystal plane from sliding eas ily over another. In others, local regions of different properties are created, also acting like raisins in the cake. But as molten metal, containing both alloying and impurity atoms, begins to cool, some segregation takes place. The atoms of the parent metal like to solidi fy as pure crystals, excluding unlike atoms. The result is that the material tends to cool as a messy aggregate of pure metal crystals, jumbled in all di rections, with impurities and alloying atoms pushed out to the crystal bound aries. Heat treatment after casting can change this situation quite a bit, but zones of potential weakness still exist at the crystal boundaries.

The same happens in welding. As the weld cools, the impurities and any ox ides formed when atmospheric oxygen gets at the hot weld metal are excluded from the solidifying weld. They are pushed toward the center of the weld, where they create an impurity zone, full of unwanted stuff. Anything above the Griffith crack dimension is ready to go to work promoting failure. Post weld heat treating tries to redissolve some of this mess or, in an analog to vacuum casting, the hot weld metal may be protected either by a slag or by inert gas shielding (Heliarc welding).

Currently, many new techniques are being brought to bear on the problem of making defect-free castings. Every part that is forged requires super-expensive forging dies. Machining parts from solid billet, less expensive than it once was because of Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines, is still quite expensive for all but modest production runs. Cast ing, which offers the greatest freedom of shape, is now getting the attention it de serves. When a de-gassed metal is poured into a mold in which it can cool in the desired way (temperature-con trolled, for example), the result can be a part whose properties are very close to those of forged or billet parts.

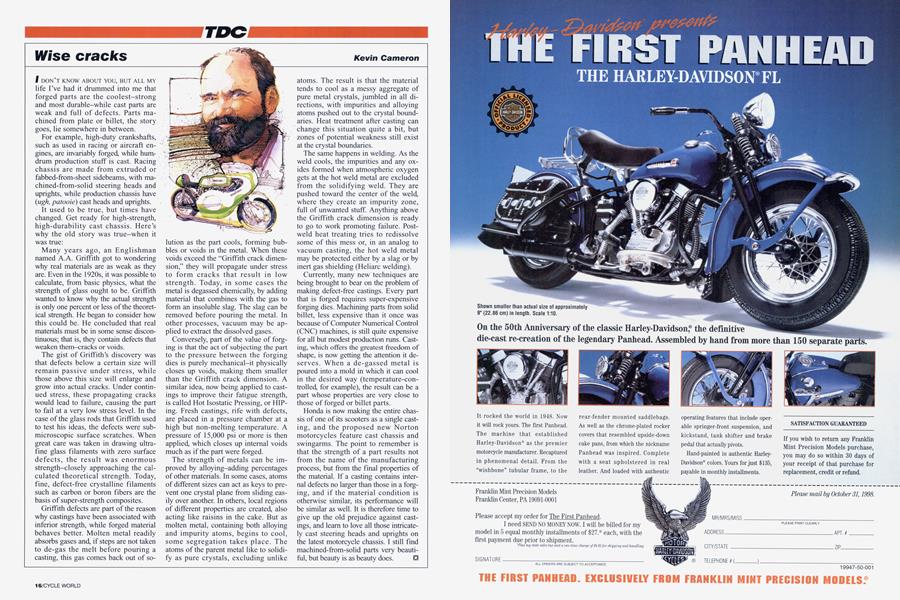

Honda is now making the entire chas sis of one of its scooters as a single cast ing, and the proposed new Norton motorcycles feature cast chassis and swingarms. The point to remember is that the strength of a part results not from the name of the manufacturing process, but from the final properties of the material. If a casting contains inter nal defects no larger than those in a forg ing, and if the material condition is otherwise similar, its performance will be similar as well. It is therefore time to give up the old prejudice against cast ings, and learn to love all those intricate ly cast steering heads and uprights on the latest motorcycle chassis. I still find machined-from-solid parts very beauti ful, but beauty is as beauty does.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue