THE NEW TWIN

BMW does a 360

As motorcycle power units go, the parallel-Twin makes great sense. It is narrow and compact, complicated enough to be sonically and mechanically interesting while being simple enough to be easy and inexpensive to build. BMW evoked classic role models such as Norton and BSA when discussing its new liquid-cooled 798cc parallelTwin, designed in conjunction with Bombardier-Rotax.

As in those classic English designs, the crankshaft is a 360-degree piece, meaning pistons rise and fall together with combustion events timed one full crank rotation apart. If you’ve ever had your vision blurred by a Norton Atlas 750, then you understand the importance of BMW’s “mass-balance” system that smoothes this dohc engine. Between the two inner main bearings lies another crank journal offset 180 degrees from those of the pistons. On this center journal is a third connecting rod, its “small end” pointing down and attached to a balance arm that runs under the engine, all of a mass to counteract that of the pistons. So as the piston and rod masses rise, so the balance arm and con-rod masses fall (and vice versa), canceling out nearly all engine vibration. The 360-degree layout gives the bike the even spark timing BMW likes for “well-balanced charge timing.” It also lends the engine note an intentional similarity to that of the classic flat-Twin.

Oil control in this semi-dry-sump design was given great attention, to the point that oil from the main bearing journals is collected in a shaft sealed off from the sump, keeping heatbuilding, power-robbing windage (it should actually be called “oilage,” according to Kevin Cameron) to a minimum. The oil tank from which the engine draws its supply is carried in a sepa-

rate chamber under the crankcase. Intake tracts for the fuel-injected 82.0 x 75.6mm cylinders are nearly vertical, and because the fuel is carried under the seat with the filler at the rear, the space under the bodywork between the aluminum frame spars is reserved for a very large, 9-liter airbox. The volume is important for supplying a large reservoir of air in a Twin that takes big “gulps” on intake, as well as for deadening intake roar. The big airbox also allows use of very long, straight intake tracts (with 46mm throttle bodies) that help produce the torque engineers were after, some 63

foot-pounds, delivered in a very linear manner. Peak output is 85 horsepower.

The four-valve cylinder head is characterized as a slice of the big K inline-Four, with similar finger followers and a 12,000-mile adjustment interval. Also like the K bike, the water pump is located on the head, minimizing hose lengths and coolant volume for lighter weight.

Fuel delivery is also of note. Most EFI systems pump to a set maximum pressure and use a

control valve to regulate that pressure, with unused fuel bled off and returned to the low-pressure side of the pump. In the F800’s case, fuel pressure varies according to demand, with no return therefore necessary. Accurate mixture control (by the usual mapped/throttle position/air pressure/temperature sensors) is aided by the oxygen sensor in the catalyst-equipped exhaust system.

Behold, the classic parallel-Twin made modern. MarkHoyer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

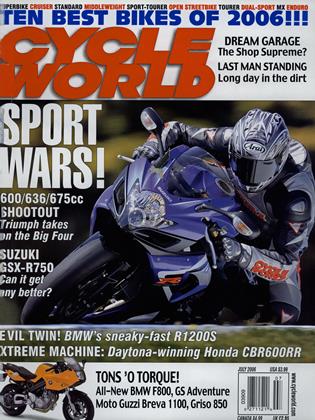

Up FrontBest of the Rest

July 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Fine Art of Riding Your Own Bike

July 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRossi's Woe

July 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2006 -

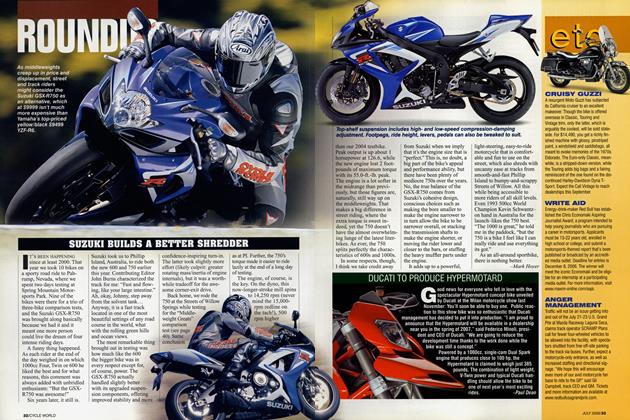

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Builds A Better Shredder

July 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupDucati To Produce Hypermotard

July 2006 By Paul Dean