Clipboard

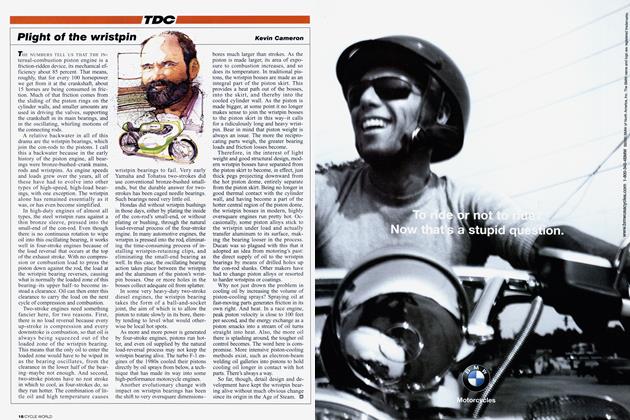

RACE WATCH

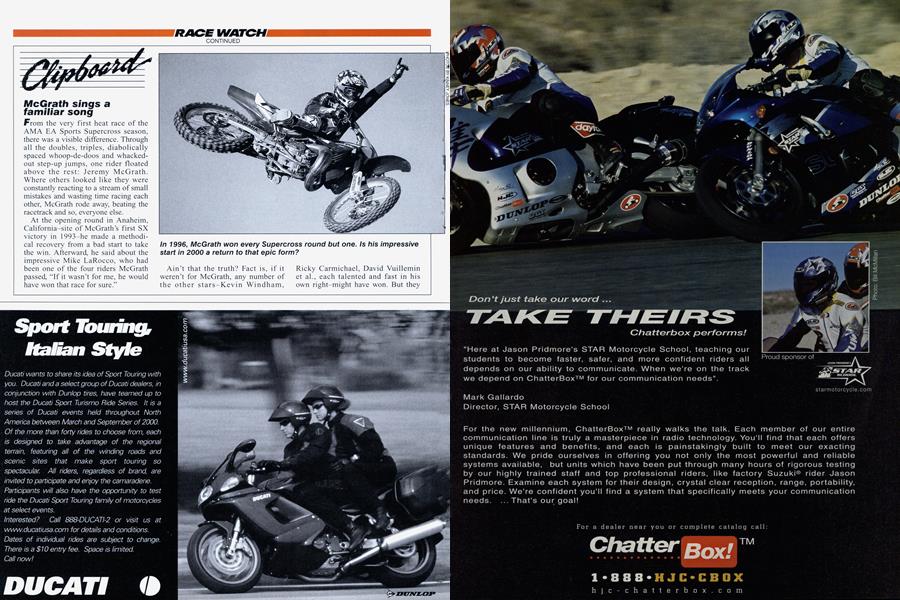

McGrath sings a familiar song

From the very first heat race of the AMA EA Sports Supercross season, there was a visible difference. Through all the doubles, triples, diabolically spaced whoop-de-doos and whacked-out step-up jumps, one rider floated above the rest: Jeremy McGrath. Where others looked like they were constantly reacting to a stream of small mistakes and wasting time racing each other, McGrath rode away, beating the racetrack and so, everyone else.

At the opening round in Anaheim, California-site of McGrath’s first SX victory in 1993-he made a methodical recovery from a bad start to take the win. Afterward, he said about the impressive Mike LaRocco, who had been one of the four riders McGrath passed, “If it wasn’t for me, he would have won that race for sure.”

Ain’t that the truth? Fact is, if it weren’t for McGrath, any number of the other stars-Kevin Windham,

Ricky Carmichael, David Vuillemin et al., each talented and fast in his own right-might have won. But they didn’t; couldn’t. And Honda’s Ezra Lusk, who won both Anaheim rounds in 1999 and was expected to be a title contender, didn’t make the main due to a separated shoulder that sidelined him for several rounds.

McGrath was equally dominant at the following event, Anaheim II, giving the trite, “Put my head down and rode my own race,” Auto-Pilot quote a new truth. McGrath is riding his own race.

As the PACE Motor Sports-promoted events get ever more slick with their tight, bang-bang schedule infused with fireworks, laser-light shows, smoke machines, spotlights and big-screen video-game promotions, don’t let it distract you from the ease with which McGrath plies his trade. Or should that be practices his art? In the same way that a layman could watch Michael Jordan soar above the rest and plainly see His Airness was better, so is it with McGrath.

Amid the slick, circus-like din of the stadium’s Big Show, the curtain only really goes up when “Showtime” hits the track. You owe it to yourself to go watch him play, because only the best make it look that way.

Mark Hoyer

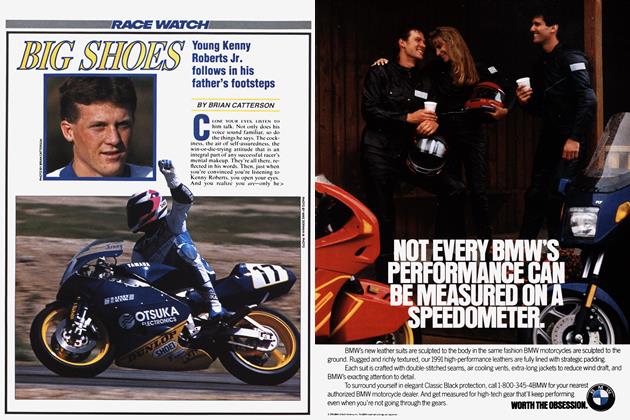

Tiny Italjet takes on the big boys

If you had glimpsed behind the curtain at a 1999 Grand Prix roadrace, beyond the spotlit battle for the 500cc crown between Alex Criville and Kenny Roberts, away from the glare of flamboyant 250cc champ Valentino Rossi, you’d have seen, lurking in the shadows, the 125s. The class is largely unheralded in the U.S., but nonetheless produces great racing, and serves as an important stepping stone to the larger divisions. Remember that Rossi was 125cc champ just three seasons ago, yet this year signed a contract with Honda that effectively will see him replace the retired Mick Doohan in the 500cc GPs.

It’s an important class, in other words, with spare-no-expense competition between major manufacturers. So there were more than a few snickers heard when lowly Italian scootermaker Italjet showed up at the Czech Republic GP.

What the snickerers didn’t know, or didn’t remember, is that Italjet is a serious player, with a proven track record. No newcomer to motorcycles, the company in the 1960s produced a Triumphpowered streetbike called the Grifón (and recently resurrected the name to adorn a Y2K equivalent), as well as a limited-production 50cc roadracer called the Vampire. Later, Italjet campaigned a 125, and won the Italian national championship in 1973 and ’74.

Last year, after an absence of a quarter-century, Italjet returned to roadracing with an all-new 125. Although the bike’s reed-valve-inducted single-cylinder two-stroke engine is based on that of a Honda RS (producing a claimed 50 horsepower at 13,000 rpm), its chassis is an original design, with a single-sided swingarm and rakish bodywork.

The team had a remarkable debut season. Riders Jaroslav “Jarda” Hules and Fabrizio Lai each scored podium finishes in the Italian national championship, and Hules wound up fourth overall in the European series. Additionally, Hules was granted a wildcard entry for his home GP at Brno in the Czech Republic, and qualified a respectable 18th before retiring from the race with a holed piston just four laps from the finish.

Now, having proven its motorcycle in competition, Team Italjet is planning to take on the world and contest the 125cc World Championship. Watch out, Aprilia. —Brian Catterson

Vintage motocross goes modern

At what point should a motocross bike be considered “vintage?” According to prevailing American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) rules, the magic year is 1974. It’s an appropriate date because it marks the turning point when short-travel suspension succumbed to the longtravel revolution, which gave us forward-mounted shocks, laid-down shocks, monoshocks and, ultimately, today’s rising-rate-linkage singleshock systems.

But for many would-be vintage motocrossers, that cut-off date is too, well, dated. The bikes they would like to race-i.e., the bikes they raced, or wanted to race, as youths-are newer than that. Barring a nationwide campaign to brainwash youngsters into wanting to race old BSAs and Matchlesses, the current crop of vintage MXers will grow old and die and there won’t be any new riders to replace them.

I’ll use myself as a convenient example. I was born in 1961, which means I’ll turn 39 this year-a prime age for an aspiring codger-crosser. I started racing MX in my teens, but because I did so on a 1975 Honda CR125 Elsinore-a bike that would be one year too new for AHRMA’s rules-I’m prohibited from reliving my youth. Much as I’d like to campaign the pre-’74 bike of my dreams, I just don’t think I'll fit on an XR75.

Fortunately, there is a move to more modern vintage motocross afoot. For the past couple of years, Rick Doughty of Vintage Iron has been promoting what he calls “Evolution” racing, which eschews a cut-off date in favor of a more technically oriented formula. Originally, there was just one set of rules, which in a nutshell said that any bike could compete as long as it had an air-cooled engine, linkageless rear suspension and drum brakes.

Doughty promoted a season-ending Evolution MX at Southern California’s Glen Helen Raceway in 1998, and was so overwhelmed by the response that he added another two classes for the 1999 iteration. The original formula now goes by the name Evolution II, while Evolution I is for pre-1978 machines and Evolution III allows liquid-cooling and linkage rear suspensions. So in essence, any motocrosser with drum brakes now qualifies as “vintage.”

Doughty was further encouraged by the turnout at the second Evolution event, to the point that he is planning three races at Glen Helen this year. Meanwhile, a new sanctioning body called the Southwest Vintage Racing Group (SVRG) has sprung up, and is now entering its second season of Vintage and Evolution MX in California and Arizona.

To its credit, stodgy old AHRMA has taken note of this emerging trend, and has added three new “Historic Motocross” classes that are only slightly more conservative than the Evolution formulae. (The timing is ironic in that Jack Turner recently replaced Jeff Smith, living icon of 1950s-60s motocross, as the organization’s Executive Director.) The first, simply called Historic, caters to the machines that started the longtravel revolution. The second, called Gran Prix, allows bikes with nonlinkage, long-travel suspension but doesn’t allow liquid-cooling. The third, called Ultima (whatever that means), allows linkage suspension and liquid-cooling but not disc brakes or exhaust powervalves.

What about bikes with disc brakes? Doughty has got a plan for those, too. While many MX sanctioning bodies already run a “Bomber” class for 10-year-and-older bikes, Doughty prefers the term “Decade.” That way, a new crop of bikes becomes eligible for vintage racing each year without sounding like they’ve been saved from the dumpster. Then again...

Me, I can’t wait for 2025, and the inevitable debate over whether to allow four-stroke Yamaha YZ400s in vintage Supercross racing and risk destroying the parity between the ubiquitous 250cc two-strokes. I think I’ll put one in mothballs, just in case.

Brian Catterson

Stefy steps up

Don’t know the name Stefy Bau? You will. The Italian motocross star is taking her place among the men this year in the AMA Supercross and Outdoor National series.

Sound ambitious? She is. Since her first race in Italy at the age of 6, Bau has attacked motocross with a passion. At age 9, she won the under-14 Italian national championship with victories in 18 of 20 races. Allowed to race 125s by age 14, she won six of seven women’s class titles. By 17, she was the Italian “men’s” amateur champ.

In 1998, Bau won the European Women’s Cup. She also traveled to Binghamton, New York, for the Women’s Motocross League final, held in conjunction with the AMA motocross national. After taking second on Friday, she flew back to Italy to win the Italian Women’s Championship on Sunday. That same weekend, she secured support from Crossroad Powersports for a full season stateside.

It paid off. Bau won all of the U.S. Women’s races. She also topped the field in both 125 and 250cc classes at the Women’s World Cup in Colorado. At Loretta Lynn’s, she had to settle for second after dislocating her wrist. But at Budd’s Creek, after winning both motos in the women’s class, she finished second behind Travis Pastrana in both A-class motos. Then, following another double at Binghamton, she entered the Pro qualifier. Unfortunately, the race was red flagged-on the last lap. Had the moto not been re-run, Bau would have qualified for the “men’s” Pro event.

This year, Bau is focusing on the AMA Supercross and Outdoor Nationals. As for Supercross, she says it may take her a few races to qualify, but that doesn’t bother her. With other options like jumping contests, videos, schools and roadracing, Bau is up for anything. “I want to be the first,” she says. “I want to be a pioneer. I can do many other things, but first I want to take motocross to its limit.”

John Light