SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Fear of flying

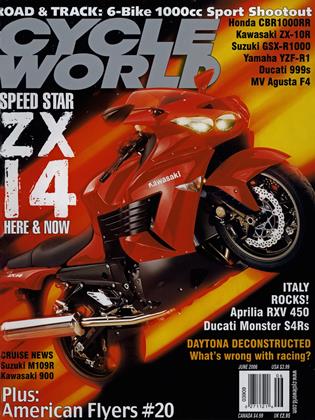

Q What’s the deal with the fly-by-wire throttle on Yamaha’s new YZF-R6? Is it an assist of some kind that works with the throttle cable or is there no cable at all and the throttle is worked electrically? If it’s only electric, that would scare the hell out of me. I may be old-fashioned, but I like having a solid mechanical connection between me and the thing that makes my motorcycle go. Randall A. Carpenter

Abilene, Texas

A Bad news, Randall: The new R6’s throttle butterflies indeed are controlled by electrical current. The throttle twistgrip is connected via a cable to a position sensor that tells the bike’s ECU (the Engine Control Unit, or main computer) how far the grip is turned, and the

ECU then sends signals to a servo motor that opens the butterflies. The ECU also controls the fuel-injection and ignition systems, so it is constantly receiving information about rpm, road speed and selected gear, among other things; it uses all that data to determine not only how far to open the butterflies but how quickly to open them for optimum airflow.

Not all is electronic, however; for safety reasons, the butterflies still are closed by a cable when you roll off the throttle.

If you are farther troubled by the idea of a computer deciding how fast and far the throttle is opened when you twist the grip, you shouldn’t be; that’s just an electronic means of accomplishing the same function performed by constant-velocity carbs, which motorcycles have used for decades. CV carbs have vacuum-controlled slides that only open as far and as quickly as dictated by intake-manifold

vacuum, regardless of how far or quickly the butterflies are snapped open by the rider. CV carbs were deemed necessary to help engines meet ever-tightening emissions requirements while also providing good streetbike rideability-functions that are gradually being taken over by electronic fuel-injection. When those functions no longer are a requirement-as is the case in various forms of racing-the stock CV carburetors usually are exchanged for slide-needle carbs on which throttle openings are determined strictly and directly by the rider’s right wrist.

I can understand your trepidation about electronic throttle operation, but this is far from new technology. Airbus commercial airliners began using fly-by-wire controls (where do you think the “fly” in that terminology came from?) back in the late 1980s, and more automobiles are being thus equipped every new-model year. The validity of this technology has been proven over and over.

Our Road Test Editor, Don Canet, is the only Cycle World staffer who has ridden the new R6, and he reports that the throttle “feels” no different than a conventional one. Yamaha evidently has done a good job of developing just the right amount of tension in the throttle return spring to give it the same resistance as one would experience with a traditional throttle. I’ve also driven numerous cars that have fly-by-wire throttles and wasn’t aware of that fact until someone later enlightened me. I suspect that if no one would ever inform R6 riders of that bike’s means of throttle operation, the vast majority of those people would never suspect that there was anything different involved in their control of the “thing that makes their motorcycle go.”

90 degrees, for instance

QI have a question about the vertical alignment of an engine’s cylinder bores with the center of the crankshaft. Am I correct in assuming that these two axes intersect? If so, what happens if we change it-i.e., move it forward; do we get a shorter power stroke and longer exhaust, or vice versa? I’m sure somebody has tried it. Will Green Nevada City, California

A Not only has a very similar idea been tried, it has been employed as a hot-rodding technique for years, and some engines are even built that way. But rather than moving the centerline of the cylinder bores forward (in the direction of crankshaft rotation), they’re moved backward by a millimeter or so. And if relocation of the cylinder bores is neither possible nor practical, the wristpin bores in the pistons can be moved rearward. In either case, the objective is to increase the engine’s torque by some small measure.

Elere’s how that works: A piston has the most leverage on the crankshaft when the angle between its connecting rod and mating crank throw is precisely 90 degrees; that event is called, logically enough, “the instance of 90 degrees.” You can liken this rod-and-throw relationship to pedaling a bicycle: Your leg has the most leverage on the pedal when it’s at a 90-degree angle to the pedal’s arm, not when the pedals are nearer the top or bottom of their rotation where that angularity is greater or lesser.

Tool Time

In the April Service department, I told you about a rugged spring hook from Motion Pro that worked about as effectively as any I had ever used. It was a well-designed tool that consisted of a strong piece of heavy-duty tempered steel wire with a hook on one end and a T-handle on the other. After the folks at CruzTOOLS read that item, they responded by sending me a spring tool of their own that adds a twist, literally, to the challenge of getting springs on or off a bike. Instead of being made of round wire, the CruzTOOLS hook is fabricated of rectangular-section, heat-treated carbon steel, which means it is very strong, and it has a CNC-machined notch at the operating end that is almost a complete circle, leaving just enough of an opening to permit a spring to enter. The shape of the notch allows you to install or remove a spring not only by pulling it, but also by pushing or twisting it. As I found during several difficult spring installations and removals, the spring tends to stay firmly hooked in fhe notch, so you can contort it in just about any way necessary to put it on or take it off. The rectangular shaft is sturdy enough to withstand any tugging or yanking you’re likely to inflict, and the PVC-coated T-handle gives your hand ample gription. The tool is called the MaxHook, its part number is SH2, and it retails for just $10 from CruzTOOLS (888/909-8665; www.cruztools.com).

Speaking of Motion Pro, one of the many motorcycle-specific tools that company sells is the Folding Sag Scale-which has nothing to do with the pay rates of unionized movie actors; it’s an elaborate ruler that helps riders set the spring sag on their bikes’ suspension systems more accurately and easily. The Scale is a ^-inchwide, 28-inch-long strip of Vs-inch-thick 6061-T6 aluminum with a spring-loaded hinge near the midpoint that allows the tool to fold to just 15Vie inches in length. At the upper end is a ruler marked in both inches and millimeters, and the lower end has a movable steel pin that can be adjusted over an 8-inch range. You use the tool much as you would a tape measure or yardstick to measure the distance from the axle to a point on the rear fender, first with the suspension fully extended, then with the rider sitting on the seat and both feet on the pegs; the difference between those two measurements is the sag. The advantages of the Motion Pro Scale over other measuring devices are two; 1) By inserting the Scale’s steel pin into the is hollow on most dirtbikes and many streetbikesyou ensure that you or whomis helping you (this still is a two-person job, even with the Sag Scale) always is measuring from the same point on the axle; and 2) it eliminates the need to do the subtraction between the measurements. When taking the fully extended measurement, you adjust the pin so the ruler is zeroed at the upper measurement point; then, when you take the compressed measurement, you get a direct sag reading on the ruler, so you don’t have to go to the trouble of subtracting fractional values (“Let’s see, 13/ie minus 147/s is, uh...”). Scale’s part number is 080336, and it retails for $31 from Motion Pro (650/594-9600; www.motionpro.com).

Because the fuel mixture expands as it burns, there is a greater level of combustion pressure up closer to Top Dead Center than there is later in the piston’s downward stroke. But when the instance of 90 degrees occurs in an engine, the piston is fairly far down in the bore. So, if the piston could be higher in the bore when the rod-crank relationship is at 90 degrees, it would be subject to greater combustion pressure and, therefore, exert more force on the crankshaft at its most advanta geous point. The result? More torque.

Homebrews

While changing my bike’s engine oil, I got some of the dirty oil on my carport’s bare, untreated concrete floor. I didn’t want my 3year-old grandson to get in the oil; you know how moms are! My daughter told me about the stain removers she uses on clothes and how well they work, so I tried one. After a few paper towels and some Shout stain remover, all of the oil was gone-and I mean gone. Most of the time, oil removers leave a thin film of oil residue in the concrete unless you use the really dangerous stuff that’s acid-based. But when I sprayed some water on that spot, there was no oil film. Best of all, the stain remover is biodegradable! The problem is, it cleans so well that I now have a very clean spot on the concrete! Ron Ware San Jose, California

That’s a new one on me, Ron. I’ll have to try some Shout on my driveway, since it looks like the crash site for a 747 tanker carrying 50,000 gallons of used motor oil.

Feedback Loop

Q lwanttothankyouandvarious Cycle World readers for your help with my numerous technical problems and questions over the years. In the March issue, for e~mple, reader Jordan Thurber offered a suggestion regarding a problem with my `94 Honda VFR75O that you had addressed in the December `05 issue ("~lking on a WA"). That kind of support has been invaluable and went a long way in my Identifying what indeed turned out to be a faulty rectifier, just as you suggested. The WA is running perfectly now. Better still, your advice encouraged me to investigate the matter myself rather than farming it out to a "professional." So, I learned how to use a multimeter for the first time arid checked the charging system from begin ning to end.

I recall Kevin Cameron writing a column about dernystifying the workings of his first computer when it stopped functioning. I'm an elementary-school teacher. so figu~ng

out the problem with my VFR was a terrific reminder for me that jumping into the unknown and learning something new can be a very positive experience. After all, it's what we encourage our students to do all the time. Why shouldn't we live by the same credo?

By the way, I've given up on Nicole Kidman and moved on. Long live Naomi Watts! I guess my wiring is still faulty! James Eng Trenton, New Jersey

A Yes, It is, but thank you for using the experience with your VFR's rectifier to encourage others to venture into the unknown. Even if their efforts do not result in a solution, they usually come away somehow smarter and wiser for having made the attempt. As a teacher, you already know that. So, thanks once again. And if you really want Naomi to give you a shot, try dressing up in a gorilla suit. Size )000000000(L.

Shifting the cylinder bores or wristpins to the rear means that when the piston is at Top Dead Center, the wristpin and its mating crank throw are not on the same centerline; the connecting rod is tilted slightly backward so that it already has begun its angularity to the crank throw by a degree or two. As a consequence, the instance of 90 de grees will be reached earlier in the pis ton's downward travel. The resultant torque increases usually are small, but when an engine designer or builder is looking to extract every last drop of performance, this is just one of many small-gain tuning techniques that can be very useful.

Hot times in Alabama

Q I've subscribed to Cycle World for years and based the purchase of my 2006 Suzuki SV650 on what I read in your magazine. I now have a question about the bike that I can't get anyone to answer. What is the normal operating temperature supposed to be? The SV currently has about 350 miles on it and usually runs consistently around 185-200 degrees, getting up to 220 every now and then before the fan kicks in. The owner's manual says that if the engine reaches 248 degrees, it should be shut down. Well, 220 to 248 degrees is not that large of a gap. Is this temperature range normal? Stacy Lewis Mobile, Alabama

A Actually, in these days of evertightening emissions regulations, the 28 degrees between 220 and 248 is a relatively large gap in engine operat ing temperatures. Ideally, the manufacturers like the engines to run right around 190200 degrees, a range that strikes a good bal ance between being hot enough to help reduce exhaust emissions (by burning those last remaining combustibles before they rush out the exhaust) and not so hot as to cause pre-ignition or other heat-related engine problems. Sometimes, like in slow traffic on a hot day or when lugging up a long hill, the temperature can rise to 210-220 degrees. The electric fan then engages to draw more cooling air through the radiator and drop the temps back into the desired range.

If, however, the temperatures climb too high, serious engine damage can result. The oil can lose enough viscosity to begin allowing metal-to-metal contact between interacting components, and the combustion event can be triggered prematurely by the surface heat of the valves, cylinder head and piston. That irregular combustion can burn valves, melt piston crowns and cause piston seizures. The engineers at Suzuki apparently have determined that 248 degrees is the critical temperature on the SV650, so they’ve recommended engine shut-down at that point. (If you’re wondering why they arrived at an “uneven” number like 248, remember that Japanese engineers use the metric system in which temperatures are expressed in Celsius, and 248 degrees Fahrenheit is an even 120 degrees Celsius.) In all likelihood, the SV engine can withstand even higher temperatures than that, but Suzuki, like all manufacturers, chooses to err on the safe side rather than recommend a temperature that is right on the edge of destructiveness. So, don’t worry; your SV’s engine temperatures are right where they should be.

Winning the cold war

QI have a 2001 Triumph Bonneville that is just about impossible to get started when the temperature is 40 degrees or less. No one in the Triumph organization seems to want to talk to me about this, so what do you think is the problem and its solution?

Richard Coleman Bay City, Michigan

Ain all likelihood, the hard starting in low temperatures is somehow related to the engine not getting sufficient fuel when it is cold. To begin with, the Bonnevilles have very lean pilot-system jetting that causes their idle to be a bit iffy even when warm. Plus, the rubber intake-manifold boots sometimes develop cracks that allow air to enter the intake stream and further lean out the mixture. And if the linkage on the carburetors’ cold-start enricheners has gotten out of adjustment, the enricheners will not deliver an adequately rich mixture to allow easy cold starting. Any one or all of these conditions could be the cause of your Bonnie’s reluctance to start when the temperature drops.

In any event, you should consider replacing the stock pilot jets in both carbs with #42 jets, then turn the idle-mixture screws all the way in and back them out two full turns. That will get you in the ballpark as far as idle mixture is concerned; you can fine-tune the mixture and speed adjustments for your region’s air density after the engine is started and fully warmed. Next, with the engine idling, spray some WD-40 all around the rubber boots on the intake manifolds; if the boots are leaking, either the engine will stall or the exhaust will emit white smoke. If either happens, you’ll know that the boots are leaking and need to be replaced. Then check the linkage that opens the enrichener circuits when the “choke” knob is pulled to make sure the enrichener plungers on both carbs are being lifted to their fully open position; if they are not, adjust the linkage accordingly.

Candid Cameron

Ql and always usually read find your it very TDC informative. column first So, could you please explain the advantages of the 270-degree crankshaft Triumph is now using on some of its vertical-Twin models? I don’t get it. Are there horsepower or torque advantages to this design? Reg Collins Noblesville, Indiana

A There are a couple of reasons to do a 270 engine. If you have two pistons going up and down together, as with a 360degree setup, both stop at TDC and BDC together. This means the crank must slow down and speed up twice per revolution as the pistons accelerate and decelerate.

This crank-speed variation adds problems because the cams are likewise varying in speed, so loads in the gearbox become “lumpy” rather than smooth. If you put one piston 90 degrees ahead of the other, then

when one piston is stopped, the other is near its position of maximum velocity (it’s actually at about 76 degrees ATDC, but nothing’s perfect). This means the pistons trade kinetic energy back-and-forth with each other, not back-and-forth with the crank. As a result, the rotation of the crank becomes a bit smoother. This isn’t a big deal, but it is a real effect, though it makes the engine harder to balance.

The other reason to do this kind of engine has to do with sound. A lot of people like the sound of a V-Twin more than they do the more monotonous “drone” of a classic parallel-Twin. The difference is that the parallel-Twin fires every 360 degrees-it is an “even-fire” engine. But a parallel-Twin engine with one piston advanced 90 degrees over the other sounds very much like a Ducati, since it fires at 270/450 degrees, just like a 90-degree V-Twin-Kevin Cameron

And finally, make sure you are using the enricheners properly. For these devices to function as intended, the throttle should remain closed while the engine is cranking. The cold-start circuits rely on a high level of intake-manifold vacuum to draw fuel up from the float bowls; but if you open the throttle at cranking speeds, the vacuum drops so dramatically that it can’t suck sufficient fuel up into the intake stream to support cold-engine combustion. If you carefully follow this procedure, you should be able to get your Bonneville to fire up any time, even when the outside temperatures are well below 40 degrees.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue