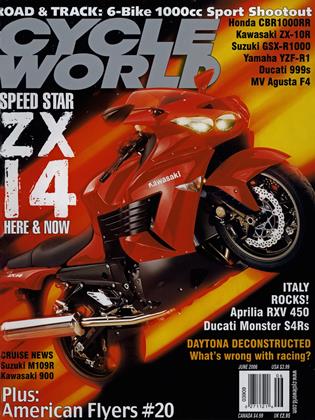

CW FIRST RIDE

KAWASAKI ZX-14

Tempered Madness

DON CANET

THE IDEA OF RIDING A MOTORcycle that produces a claimed 187 horsepower (197 with ram air in effect) is in itself enough to make your knuckles lose their color. Now imagine slinging such a machine around a NASCAR oval lined with an unprotected concrete wall! Heck, even the thought of launching such a rocket down an arrow-straight strip made my neck hair stand on end considering the prospect of a sudden wheelstand or loose ’n’ wooly wheelspin through the lower gears...

I was shocked to discover that the most powerful production motorcycle ever offered to the public made easy work of both these venues. Kawasaki’s highly anticipated ’Busa-bustin’ Ninja ZX-14 has not only raised the power bar, but its incredibly rider-friendly nature and smooth delivery has set a new standard among powerhouse machines.

As with all Open-class roadburners built since the turn of the century, the ZX-14 is electronically limited to a top speed of 186 mph, a figure that meters out to a nice round 300 kph. While the new Ninja doesn’t violate the industry’s voluntary top-speed treaty, it serves notice that the contest of who can get there quickest is still on. You can bet Suzuki, which sold 10,000 Hayabusas in the U.S. last year, is paying attention (and maybe Honda-see Roundup this issue). A new Hyper-Busa is heavily rumored to be far along in development and could surface in 2007.

Kawasaki invited the motorcycle press to flog its new flagship machine in a controlled racetrack environment at Las Vegas Motor Speedway. With medical staff standing by and traffic cops nowhere in sight, we were cut loose aboard the big Ninja on the speedway’s 1.5-mile banked tri-oval and neighboring quarter-mile dragstrip. Once our speed fix had been indulged, the plan called for a mellow, “law-abiding” street ride on local mountain roads the following day.

One rider at a time, we put in five-lap stints on the oval, working the rotation three times through before moving over to the dragstrip. Along with hammering out complete laps at speed, I used this opportunity to conduct roll-ons down the back straight from various rpm in each gear. I was surprised by how sedate the engine felt below 5000 rpm, as it lacked the kind of low-end grunt that I recalled having experienced aboard a Hayabusa or ZX-12R. Kawasaki has tamed the 14’s low-rev delivery intentionally and, in the process, has completely eliminated the on-throttle abruptness that hampered the 12R. Snapping the 14’s throttle open quickly at low revs actuates electronic intervention-the ECU is programmed with a rate-of-acceleration map that controls ignition timing and the speed at which the secondary throttle valves open. My seat-o’-the-pants accelerometer suggests that all of the bottom four gears of the six-speed box are affected, evidenced by a sensation that fifth seems to pull as hard, if not harder, than fourth between 3000 and 5000 rpm.

Even with the electronic countermeasures, there's more than enough torque on tap to satisfy any real-world riding situation. I wouldn't be too quick to trade the controlla bility and minimal drivetrain lash for a harder hit. Besides, once the tacho needle sweeps past 6000 rpm, it's unadulter ated fast times all the way to the 11K redline.

Serious business, these 200 ponies, as evidenced by streaks of tire rubber mea suring a couple hundred yards in length that the ZXs painted through the tn-oval bend adjacent to pit lane. Even more aston ishing, we topped fifth gear through that section with the throttle pinned and the speedometer registering over 180 mph. I'd estimate actual speed closer to 160 due to speedometer error while leaned over on the sides of the Bridgestone radials. Equally impressive was the big Ninja's high level of stability and line-holding ability when carrying fifth gear through the banking at both ends of the oval, a relaxed hold on the bars allowing the chassis to settle in with minimal movement.

The afternoon was spent at the dragstrip, where we received tips and advice from Kawasaki factory drag racers Rickey Gadson and Ryan Scbnitz, who have 10 national titles between `em. Here again, the ZX amazed at not only its ability to sprint on record pace, but also the ease at which it achieves this. The ZX utilizes a radial-pump master cylinder for clutch actua tion. Kawasaki claims this setup offers more direct feel than traditional hydraulic arrangements, and I'd have to agree. Most of the riders taking part were able to control clutch slip throughout first gear and post sub-10.5-second runs. Equally astonishing was the durability of the clutch pack itself, as the bikes were flogged over two days with no failures to report.

Another unique feature of the ZX with respect to drag racing is a programmable shift light that also serves as a launch light. This feature can be set to illuminate at the rpm you want to hold at the line. I didn't find the light very useful, however, as it’s located low in the dash, well outside the rider’s peripheral vision when attention is focused ahead on the start tree. Perhaps Kawasaki could implement a two-step launch rev-limiter that holds rpm at a programmable level when the clutch is disengaged? In certain circles, that would be a huge sales feature.

Gadson advised that 4000 rpm was a good launch point for the conditions, with the goal being to feed in throttle and clutch throughout much of low gear. Grabbing upshifts at 11,000 rpm was a matter of hitting the shift light’s cue. The bike’s linkage-less shifter offers precise feel and light action; I didn’t hear a single rider miss a shift or have a bike jump out of gear all afternoon. Even facing a stiff sidewind, the bike tracked straight throughout each run. I also used the run out beyond the speed trap to test the power of the radialmount front brakes, which proved to be as strong and consistent as the stellar stoppers on the new ZX-1 OR.

While my personal bests on the ZX were a pair of 10.08second/ 142-mph runs (corrected to sea level, 9.90/145), quickest on the day was a corrected 9.73-second pass by wxvw.motorcycle-usa.corn's Kevin Duke, a skinny scribe with excellent clutch feel.

Weather put a damper on Day Two, with reports of snow in the mountains. We took an alternate street route that included a freeway stint, the final destination being a painfully slow drone through a scenic state park with a 25-mph posted speed limit. Definitely not Ninja Territory.

Arrggh! What a tease this turned out to be as we followed our prudent ride guide along a curvaceous ribbon of tarmac without a chance to put the bike’s power and handling to good use. Sort of like entering a Vegas strip club with a $100 bill that no one will break.

The irony is, I passed up the option of remaining at the speedway for additional dragstrip time. Obtaining a street impression was a priority, but it was a difficult choice as the wind had shifted, and flags flying above the strip pointed in a direction indicating the possibility of hero numbers being posted.

Nonetheless, I set sail on the 1-15, noting 45 mpg displayed on the LCD dash as I maintained an indicated 75 mph at 3500 rpm during our downwind leg. Bucking a headwind on the return trip set things straight with a 30mpg reading. The dash consists of large analog tachometer and speedometer dials flanking a multi-function LCD panel. The LCD features a clock, gear-selection indicator and bar graphs showing coolant temperature and fuel level. Along with an odometer and dual tripmeters, there’s a trip computer that can be toggled to show fuel range and average or instantaneous fuel mileage. All very useful features, especially considering that the bike offers a high degree of comfort seemingly well-suited for longer hauls.

The saddle is well-padded and nicely shaped, narrow at the front to allow a firm footing at stops and broad rearward to provide plenty of comfort and support. Pegs are set low for ample legroom, while the handlebar position strikes a fine balance between comfort and sport. The fairing and windscreen provide good coverage and minimal buffeting around the helmet. The engine features a pair of gear-driven balancers, one of which resides in front of the crank-like that of the 12R-and a secondary balancer located aft of the cylinder bank. Engine vibration is very mild at a steady cruise and remains remarkably low even when power is applied. This is impressive considering that the ZX-14 employs solid engine mounts, making the engine a stressed frame member, which in turn has resulted in a lighter structure yielding more chassis rigidity than that of the 12R.

Despite its increase in capacity, the engine is no larger physically than its predecessor. The all-new alloy monocoque frame wraps over the top of the cylinders rather than to the sides-tf la the ZX-12R-making the Ninja much narrower than a Hayabusa. The airbox is incorporated into the frame, as is the battery holder. Although fuel capacity has been increased to 5.8 gallons, the tank extends down and under the seat for more centralized mass while reducing the width of the tank where it meets the rider’s knees.

The tidy riding position combined with solid-mounted pegs and bars deliver direct feel and good steering response. From parking-lot maneuvers to high-speed cornering, the chassis steers with an ease unlike that of any large capacity road-burner I’ve ridden.

Upon our return to the speedway, activity was winding down at the dragstrip but the air was charged with energy. Several riders, some with no prior drag-race experience, had dipped into the high 9s. Duke, damn him, ducked under 9.50 seconds corrected to sea level. Impressive stuff!

And a little problematic. Sanctioned dragstrips across the country require anyone turning sub-10-second runs to hold an NHRA license. It seems a membership drive is imminent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue