Ride a Crroked Road

TheNEW Standaeds SPECIAL SECTION

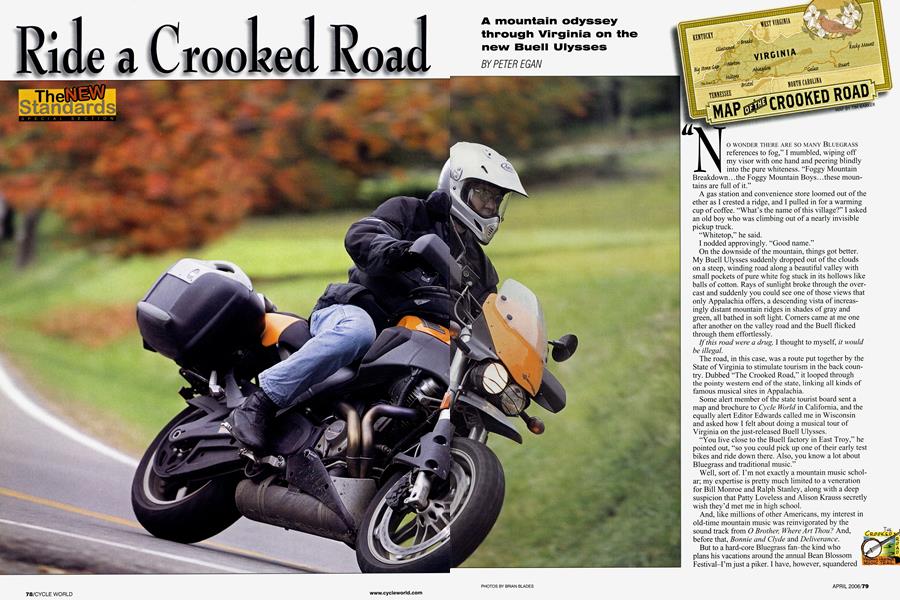

A mountain odyssey through Virginia on the new Buell Ulysses

PETER EGAN

"

N

0 WONDER THERE ARE SO MANY BLUEGRASS references to fog," I mumbled, wiping off my visor with one hand and peering blindly into the pure whiteness. "Foggy Mountain Breakdown. . .the Foggy Mountain Boys.. .these moun tains are full of it."

A gas station and convenience store loomed out of the ether as I crested a ridge, and I pulled in for a warming cup of coffee. “What’s the name of this village?” I asked an old boy who was climbing out of a nearly invisible pickup truck.

“Whitetop,” he said.

I nodded approvingly. “Good name.”

On the downside of the mountain, things got better.

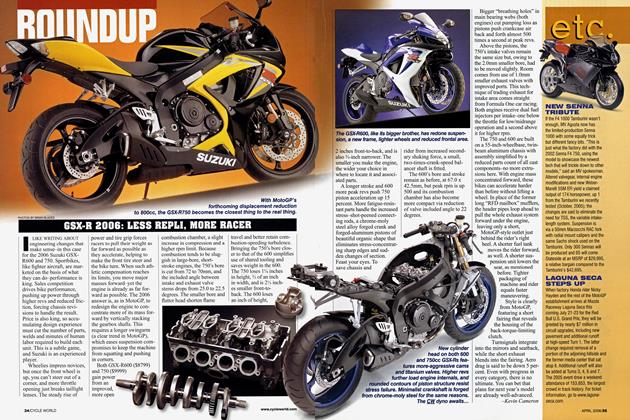

My Buell Ulysses suddenly dropped out of the clouds on a steep, winding road along a beautiful valley with small pockets of pure white fog stuck in its hollows like balls of cotton. Rays of sunlight broke through the overcast and suddenly you could see one of those views that only Appalachia offers, a descending vista of increasingly distant mountain ridges in shades of gray and green, all bathed in soft light. Comers came at me one after another on the valley road and the Buell flicked through them effortlessly.

If this road were a drug, I thought to myself, it would be illegal.

The road, in this case, was a route put together by the State of Virginia to stimulate tourism in the back country. Dubbed “The Crooked Road,” it looped through the pointy western end of the state, linking all kinds of famous musical sites in Appalachia.

Some alert member of the state tourist board sent a map and brochure to Cycle World in California, and the equally alert Editor Edwards called me in Wisconsin and asked how I felt about doing a musical tour of Virginia on the just-released Buell Ulysses.

“You live close to the Buell factory in East Troy,” he pointed out, “so you could pick up one of their early test bikes and ride down there. Also, you know a lot about Bluegrass and traditional music.”

Well, sort of. I’m not exactly a mountain music scholar; my expertise is pretty much limited to a veneration for Bill Monroe and Ralph Stanley, along with a deep suspicion that Patty Loveless and Alison Krauss secretly wish they’d met me in high school.

And, like millions of other Americans, my interest in old-time mountain music was reinvigorated by the sound track from O Brother, Where Art Thou? And, before that, Bonnie and Clyde and Deliverance.

But to a hard-core Bluegrass fan-the kind who plans his vacations around the annual Bean Blossom Festival-I’m just a piker. I have, however, squandered wmm TEAI

lots of money on books and exploratory CDs, so I guess .o you could say I'm a student of the art form. And what better thing for a student than a class trip like this one9 Also, I was keen to put some road miles on a Ulysses, as it's one of a small handful of new bikes on my ownership radar. Off to East Troy.

I picked up the Buell with my van, brought it back home, packed the voluminous saddlebags and a duffel bag with enough riding gear to theoretically survive all the variations of mountain weather in October, said goodbye to Barb and rode south at sunrise on a Tuesday morning. It took me two days of steady riding to reach Virginia. I left Wisconsin, blitzed down the Interstate to Bloomington, Illinois, and then headed diagonally across Indiana on twolane roads. I stopped for the night in Madison, Indiana, a beautiful old town on the Ohio River. After checking into a hillside hotel, I walked downtown for dinner and a movie. The theater was showing the highly acclaimed documen tary, March of the Penguins, in one auditorium and Dukes of Hazzard in the other. A recent review of the latter in our local paper had called it (and I quote here from memory), "A really bad movie made from one of the dumbest TV shows in history." I looked at the posters in front of the theater and noticed there were no `68 Dodge Chargers or girls wearing short shorts in March of the Penguins, so I naturally went to Dukes of Hazzard.

It wasn't as bad as I expected, and it had Waylon Jennings in the soundtrack. Some things you have to do for Art. On a foggy morning, I crossed the Ohio and climbed into the warm sunlit hills of Kentucky. Farm stands along the road were laden with Indian corn, yellow squash and pumpkins almost the same color as the airbox cover in front of me.

The Buell was booming along nicely, the 1203cc Twin cranking out tons of easy torque. The engine shows its Harley heritage at idle, shaking up and down in its rubber mounts, but transforms itself into a smooth runner when yo start rolling. It revs freely and easily to its 7500-rpm redlin but seldom needs to be revved past 5000, with all that mid range wallop. And the sound is deep and throaty. Gears are well-spaced, but you rarely have to shift and cai dial speed on and off with the throttle in fourth or fifth on a twisty road. When you do shift, clutch pull is light and the thing changes gears with quiet, well-oiled precision. Nice gearbox. Superb brakes, too.

1Jp1%~~aI `~)i ii1~J~ _)1J~%.,~3 IIalltlItIl5 I~ effortless and reassuring. Erik Buell makes much of his engi neering efforts at mass centralization (short exhaust canister under the engine), low unsprung weight (perimeter brake rotor on a very light wheel) and weight-saving cleverness (oil res ervoir in hollow swingarm), but it all pays off in agility, han dling and ride. This is a really fun bike that works with you on a backroad. The ride is compliant, well-damped and civilized. It ain't bad on the Interstate, either. The bike is a little windy at 70-80 mph with its short, snap-on-and-off windscreen (a larger optional one is on the way), but the roomy riding posi tion is just about perfect for all-day travel. So is the seat, which may be the best-designed, most comfortable perch available on any modern motorcycle. I spent seven days and 2200 miles in this saddle and never gave it a thought. Note to BMW, Ducati and KTM: Quit fool ing around and just copy this seat.

The Buell carries its 4.4 gallons of pre mium unleaded in the perimeter frame/gas tank, and range can vary widely depend ing on how and where you ride. On the Interstate, I averaged about 41 mpg and the fuel light came on around 155 miles. Following coal trucks through mountainous West Virginia on the way home, I averaged 57 mpg.

Any downsides?

Riders with short inseams will find the bike tall and a bit clumsy at stop signs and in slow maneuvers. Also, a noisy electric fan that cools the rear cylinder stays on for about a minute after you shut off the ignition. When you stop to ask for directions, it roars away.

The engine probably needs it, though. On a hot day, the frame/gas tank gets quite hot to the touch, particularly on the right side, even with the fan running.

And the weather stayed warm and beautiful all the way into Kentucky on Highway 421, a zone of old cabins, deep valleys and tobacco barns. I turned onto Highway 460 and the state morphed into horse country, with huge estates and miles of white fences. Places where big pillars and gates say “Hey, look over here! I’m rich!”

That evening I crossed into Virginia to the official starting point of the Crooked Road. This was a mountaintop park that straddles the Kentucky/Virginia border, called Breaks Interstate Park. I stayed at the park lodge and took advantage of its deck looking out on a gorge with rock chimneys and a river far below. In the morning, I was supposed to meet Brian Blades, our photographer who had flown in from California and rented a car at the Bristol airport.

The steep mountains precluded cell phone service-which was lucky, because I don’t own a cell phone and Brian’s was broken-so we agreed to meet at the Breaks village post office at noon. Brian was a little late, so I got to talk to dozens of people who came to pick up their mail.

One older gent by the name of Tom Blankenship told me he’d been a coal miner for 24 years until the local seams played out, then built Cadillacs and Chevys in Detroit. Now he was picking ginseng in the forest for a living. He asked where I was heading and I said, “Down to Clintwood, which is Ralph Stanley’s home town.”

He nodded. “I know old Ralph. Everyone here knows him. He’s kin to my wife. Her mother was a Stanley. Ralph and the Clinch Mountain Boys are playing tomorrow night at the theater in Clintwood. You might want to see ’em.”

Good tip.

Brian hove into view with his rental car, and soon the Ulysses was descending into legendary Dickenson County on tight, winding Highway 83 in a light rain. I rumbled into the small town of Clintwood and stopped on Main Street at the Jettie Baker Center, which had “Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys” on the marquee. Friday night.

This was only Thursday, so I decided to continue south and somehow backtrack the next night for the show. I took a wrong turn leaving town and did an accidental 70-mile loop through Appalachia and ended up back in Clintwood two hours later. It’s hard to sense your direction in these mountains when the sun’s not shining. I’m surprised Daniel Boone didn’t end up in Newark.

I finally rode into Norton, the next star on Virginia's Crooked Road map. Outside of Norton was a famous old place called the Country Cabin, built in the 1930s as a corn munity recreation center for dances, music, cakewaiks, hoedowns, box suppers and other entertainments whose allure has been partly lost to youth since the inven tion of the Marshall 100-watt stack and the ;`~ reign of Sid Vicious

Across the street from the original site is Country Cabin II, a larger log hail that holds more people. Unfortunately, the place was closed until Saturday's Bluegrass night, so I looked in the darkened windows, hoping that bad timing would not turn this into the Closed Building Tour.

On the door were rules of behavior for music nights: no drinking, guns or other weapons, unruly behavior, harassment of others, vulgar language, etc.

This train don’t carry no gamblers, this train. Bluegrass is essentially a culture of modesty and good manners, the flip side to Rock’s experiments in sullen nihilism. You’d be just as likely to see a space launch at a Bluegrass festival as to hear the F-word spoken.

Near Norton I motored down a deep valley behind a coal truck and suddenly realized the road was covered in fine coal dust. Along the highway I saw my first big coal processing plant and stopped for a look. Glancing in the mirror, I saw a face with a raccoon mask of carbon looking back at me. You could get black lung here just reading the fine print on someone’s bumper stickers.

As I headed through the valley, a small drive-in movie theater appeared (Bad News Bears), tucked into a small parcel of flat land. On both sides of the road, old houses and mobile homes clustered in deeply shaded hollows and ravines, and it occurred to me that opportunity here is pretty much proscribed by valleys, channeled by ridges. That isolation is a good part of what made-and preserved-the old music.

L.Y KNOWN AS It being too dark and late to search out rustic charm, Brian and I got generic hotel rooms on the highway outside Norton and ate at a generic steak house. Other than that, I remember nothing. Another case of amnesia through modern comfort. The next day the Ulysses threaded its way through old coal towns around Big Stone Gap, then headed for the next big star on our route, the little village of Hiltons, Virginia. Home of The Carter Family Fold. You might call this spot the cradle of modern Country music.

A tall, thin man named A.P. Carter lived here with his wife Sara, and they sang songs with Sara's guitar-playing sister, Maybelle In 1927 they got into their car and drove down to Bristol for a trial record ing session in an old warehouse with a talent scout named Ralph Peer. He discovered, to his amazement, that this "hillbilly" music was immensely popular with record buyers all over the country. Their songs, "Wildwood Flower" and "Will the Circle be Unbroken," are the dual anthems of Country music.

Country

Maybelle’s daughter June married Johnny Cash, and A.P and Sara’s daughter, Janette, still emcees music nights at the family home. The Carters are the Royal Family of Country Music, only without the tweeds, Wellingtons and big ears.

Peer also recorded a guy with a bluesy yodeling style named Jimmy Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” and he too became a star. I still listen to his records myself. These sessions are called “The Big Bang of Country Music.”

Anyway, the old Carter family home and grocery store is still there on a quiet rural road in Poor Valley near Hiltons, at the foot of the Clinch Mountains, and there’s an open-sided music theater built next door. I got there on a drizzly afternoon, and there were workmen renovating part of the theater.

One of them was a CW reader and avid motorcyclist. He said Janette Carter usually performed with Bluegrass groups on Saturday nights, but she’d been in the hospital and probably wouldn’t be there that weekend. Once again, I’d have to backtrack the next night to make the show. I’d see.

Motoring into the big town of Bristol, Brian and Igot motel rooms for the night. We then jumped in his rental car to retrace our route back to Clintwood to see Ralph Stanley. It was a dark and rainy night, and I didn't feel like riding over the mountains again on the Buell. I like to pay my dues, but only once.

When we got to C1intwood~ Stanley's tour bus was in front of the theater. As we stood under the marquee to keep out of the rain, Dr. Ralph Stanley himself climbed down from the bus, and I got to talk to him for a while. A nice man, alert and quick for his 78 years. Now that Bill Monroe is gone, he is really the last performing legend of mountain music, one of the greats.

Before the show, I wandered across the street to the Ralph Stanley Museum. I got there 10 minutes before they closed, but that didn’t keep me from loading up on rare Bluegrass CDs and DVDs. I got a feeling the Buell’s luggage was going to get heavier on this trip, perhaps approaching black hole density.

The show that night was terrific. Stanley has a high, lonely ache in his voice that Dwight Yoakam once called, “Ancient, in the most flattering sense of that word, and timeless.” It really is the sound of the mountains. He sang “O Death” in his haunting a cappella, a performance that brought him national fame in the soundtrack of O Brother, Where Art Thou?

I should mention, too, that the opening act, The Reeltime Travelers, was one of the best bands I’ve ever heard, and they all looked to be under 30. They had a stunning woman fiddle player who blew everyone away, as did the woman who played guitar. I think there were also some guys in the group.

Brian and I careened back down the mountain to Bristol in the fog and rain. In the morning we headed to the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, which is located on the basement level of the huge and modern Bristol Shopping Mall.

As we crossed the parking lot, I said to Brian, “This is where the Carter family did all their shopping during the Depression. They’d come in here and pick up calico and biscuit flour and then get a latte at Starbuck’s.”

The museum, however, turned out to be well worth the risky mall exposure, and the woman running it told me the mall had been kind enough to donate space until they could move into a larger and more appropriate site. Also, the place was full of music fans, even at 10 in the morning.

I unholstered my Visa card and spent a small fortune on more CDs and DVDs. The Buell saddlebags quaked in the parking lot; flocks of birds took flight in alarm; Alan Greenspan tossed in his sleep.

Winding roads, all day long. Beautiful roads with endless corners along Highway 58. We stopped first at Abingdon, a rather upscale town full of beautiful old homes and architecture, to look at the famous Barter Theater, then swung on to Galax, Virgina (pronounced “Gay-Lax,” like an over-thecounter medication). This is a pretty town in a broad valley, famous for its Old Fiddler’s Convention, held each August since 1935, and the Rex Theater, home to a nationally popular Friday night radio show called “Blue Ridge Back Roads.” There was no Bluegrass at the Rex that night, but something completely different: a Gospel celebration to raise money for Hurricane Katrina victims, organized by the local fire department. Performers and audience were mostly black, from nearby churches, and it was one of the best nights of music I’ve ever heard. Everybody sang and clapped and swayed. The local talent was amazing; Aretha Franklin meets Percy Sledge.

With volunteer work and personal donations, these smalltown citizens raised hundreds of dollars and presented the money to a young white family from New Orleans who'd lost their home. Meanwhile, American oil companies raked in billions of dollars in profits from high fuel prices after Katrina and got an enormous tax break from our government. Nice to know part of this country is still great.

From Galax, Highway 58 just got better and better. The music may hold this route together, but it needs no such justification to the motorcyclist. It’s all curves, scenery, mountains, ridges and subtly changing landscapes, down to Stuart and all the way up to the hilltop town of Floyd, where a famous record shop and the Floyd Country Store (home of the Friday Night Jamboree) were both closed, as you might expect on a Sunday afternoon.

And that’s the main problem with this tour. You need at least two weekends to do it right, rather than just one, and most things happen on Friday and Saturday nights. You have to be too many places at once. Regardless, you still hear a lot of good music, as we did, and to a motorcyclist the music is just a sidelight anyway. The Crooked Road is exactly that, and you’d have a great ride if you didn’t know Bluegrass from Shinola.

Brian and I motored up to the end of the Crooked Road at Rocky Mount, had lunch at a good Italian restaurant and split our separate ways for home. He was driving back to the Bristol airport, and I was 1100 miles from home, mostly by winding two-lane roads through Appalachia. The return trip took me two and a half days.

I rode through the stunningly beautiful and rugged moun tains of West Virginia, more raw and wild than Virginias and studded with gritty coal towns. While passing a coal truck on a mountain road, my Check Engine light came on. The engine was running fine, but I pulled over and checked the oil, which was okay. I noticed the rear cylinder cooling fan hadn't come on, as it usually did. Maybe it was running hot, and this fan was the Achilles heel of the Buell (Achilles heel on a Ulysses from East Troy? Isn t this too much Greek literature in one paragraph7) But the engine didn't feel hot, and the Buell continued to run well all the way home. Still, the engine light came on intermittently, giving me one of those dull headaches of doubt. Erik Buell later told me the first 40 bikes left the factory with defective threading on a screw that opens the exhaust system’s powervalve, and this tripped the light. Didn’t hurt anything; just reduced horsepower slightly above 5000 rpm. Now I know.

Except for that, the bike never gave me a moment of trouble. It was a good partner on this trip; quick, agile and comfortable with an engine that pulls like a truck-but much better than the trucks you pass in the mountains. Every morning, I looked forward to getting on it. Which is the big test of an adventure-touring bike.

Is it a dirtbike as well?

Not really. I ran up some rutted dirt-and-gravel roads (to look at a cabin for sale) and found the 17-inch front tire too easily deflected for serious off-road work. You can make it through, but it’s not all that much fun. What we have here, really, is a roomy, comfortable and charismatic sportbike that lets you travel long distances and carry luggage while you sit up and enjoy the scenery.

And there was plenty of that on the Crooked Road.

If you showed the public some good color photos of rural Virginia and said they were NASA pictures from a distant planet, people would sell everything they owned and pay a million dollars for a one-way ticket on a space ship. Their hearts would ache with a desire to move there. It’s that beautiful.

But it's not on a distant planet. It's right here on Earth, in a quiet corner of Virginia, haunted with old cabins, half-forgotten villages, brooding forests and the echoes of ancient Celtic music with a high and lonesome sound. And the occasional motorbike on some kind of odyssey. You can ride there from your home