GPS vs. The Classic Map

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

IT WAS 5 BELOW ZERO HERE IN WISCONSIN this morning, so I cleverly decided to drink coffee and read the paper instead of tak inga ride.

After the mandatory scan of motorcy cle want ads (slim pickin's in winter), I found myself reading a column called "Tech Smart" (quite beneficial to those of us who are "Tech Stupid") and ran across a product review of a new portable GPS unit.

It said this small, hand-held device con tained not only a satellite navigation sys tem, "but also a built-in music player, photo viewer, U.S. travel guide, audio book reader, language translator, curren cy converter and more."

Iset the paper down on my lap and stared into space. Who would build such a thing and not include an electronic gui tar tuner?

I mean, if you're going to replace cv cry appliance in your house, why not go all the way and help the customer tune his Rickenbacker 12-string? Just kidding, of course.

As one who can barely program the ra dio/alarm clock in a Motel 6, I'm always leery of these multi-tasking devices. Af ter all, the word processor on which I am writing this column is the least reliable thing I've ever owned, including my first Norton. It shuts down, changes its mind, reformats, crashes and suddenly asks in comprehensible questions ("Would you like to destroy all existing files or just set your keyboard on fire?") seemingly at ran dom. If my old Olivetti portable typewriter had given me this much trouble, I would have thrown it off a bridge.

In other words, I don't trust computer chips to do even one thing correctly, let alone six or seven. Nevertheless, I have to admit that the GPS unit in the newspa per story caught my eye. Why? Well, I consider the Global Positioning System to be an outright miracle of human in~enuitv.

Like manned flight, it's something our ancestors dreamt about, through all those centuries of astrolabes, sextants, reading ocean cunents, struggling to compute lon gitude, watching the stars and leaving trails of bread crumbs. Right after "Why can't I fly?" the second most common question in history has probably been, "Where the hell am I?"

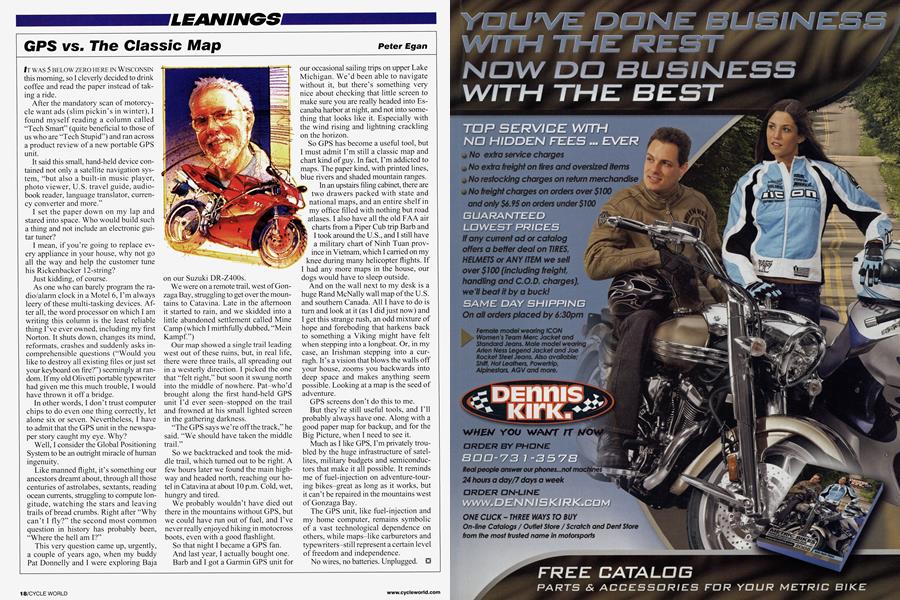

This very question came up, urgently, a couple of years ago, when my buddy Pat Donnelly and I were exploring Baja on our Suzuki DR-Z400s.

We were on a remote trail, west of Gon zaga Bay, struggling to get over the moun tains to Catavina. Late in the afternoon it started to rain, and we skidded into a little abandoned settlement called Mine Camp (which I mirthfully dubbed, "Mein Kampf.")

Our map showed a single trail leading west out of these ruins, but, in real life, there were three trails, all spreading out in a westerly direction. I picked the one that "felt right," but soon it swung north into the middle of nowhere. Pat-who'd brought along the first hand-held GPS unit I'd ever seen-stopped on the trail and frowned at his small lighted screen in the gathering darkness.

"The UPS says we're off the track," he said. "We should have taken the middle trail."

So we backtracked and took the middie trail, which turned out to be right. A few hours later we found the main high way and headed north, reaching our ho tel in Catavina at about 10 p.m. Cold, wet, hungry and tired.

We probably wouldn't have died out there in the mountains without GPS, but we could have run out of fuel, and I've never really enjoyed hiking in motocross boots, even with a good flashlight.

So that night I became a GPS fan. And last year, I actually bought one. Barb and I got a Garmin GPS unit for our occasional sailing trips on upper Lake Michigan. We'd been able to navigate without it, but there's something very nice about checking that little screen to make sure you are really headed into Es canaba harbor at night, and not into some thing that looks like it. Especially with the wind rising and lightning crackling on the horizon.

So GPS has become a useful tool, but I must admit I'm still a classic map and chart kind of guy. In fact, I'm addicted to maps. The paper kind, with printed lines, blue rivers and shaded mountain ranges. In an upstairs filing cabinet, there are two drawers packed with state and national maps, and an entire shelf in my office filled with nothing but road `atlases. I also have all the old FAA air charts from a Piper Cub trip Barb and I took around the U.S., and I still have a military chart of Ninh Tuan prov ince in Vietnam, which I carried on my knee during many helicopter flights. If I had any more maps in the house, our dogs would have to sleep outside.

And on the wall next to my desk is a huge Rand McNally wall map of the U.S. and southern Canada. All I have to do is turn and look at it (as I did just now) and I get this strange rush, an odd mixture of hope and foreboding that harkens back to something a Viking might have felt when stepping into a longboat. Or, in my case, an Irishman stepping into a cur ragh. It's a vision that blows the walls off your house, zooms you backwards into deep space and makes anything seem possible. Looking at a map is the seed of adventure.

GPS screens don't do this to me. But they're still useful tools, and I'll probably always have one. Along with a good paper map for backup, and for the Big Picture, when I need to see it.

Much as I like GPS, I'm privately trou bled by the huge infrastructure of satel lites, military budgets and semiconduc tors that make it all possible. It reminds me of fuel-injection on adventure-tour ing bikes-great as long as it works, but it can't be repaired in the mountains west of Gonzaga Bay.

The GPS unit, like fuel-injection and my home computer, remains symbolic of a vast tecimological dependence on others, while maps-like carburetors and typewriters-still represent a certain level of freedom and independence. No wires, no batteries. Unplugged.