Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Quickest of the Quick

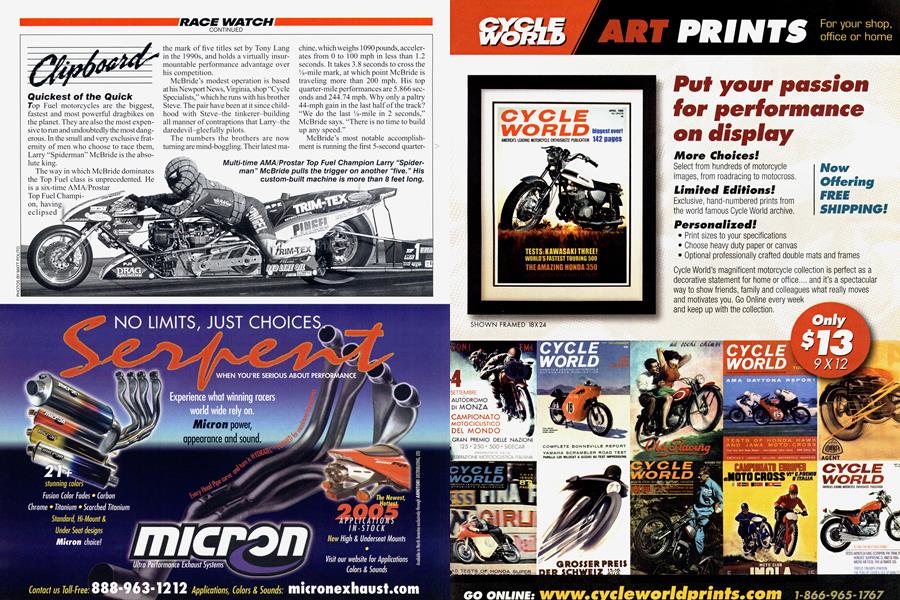

Top Fuel motorcycles are the biggest, fastest and most powerful dragbikes on the planet. They are also the most expensive to run and undoubtedly the most dangerous. In the small and very exclusive fraternity of men who choose to race them, Larry “Spiderman” McBride is the absolute king.

The way in which McBride dominates the Top Fuel class is unprecedented. He is a six-time AMA/Prostar Top Fuel Champion, having eclipsed the mark of five titles set by Tony Lang in the 1990s, and holds a virtually insurmountable performance advantage over his competition.

McBride’s modest operation is based at his Newport News, Virginia, shop “Cycle Specialists,” which he runs with his brother Steve. The pair have been at it since childhood with Steve-the tinkerer-building all manner of contraptions that Larry-the daredevil-gleefully pilots.

The numbers the brothers are now turning are mind-boggling. Their latest machine, which weighs 1090 pounds, accelerates from 0 to 100 mph in less than 1.2 seconds. It takes 3.8 seconds to cross the Vs-mile mark, at which point McBride is traveling more than 200 mph. His top quarter-mile perfonnances are 5.866 seconds and 244.74 mph. Why only a paltry 44-mph gain in the last half of the track? “We do the last Vs-mile in 2 seconds,” McBride says. “There is no time to build up any speed.”

McBride’s most notable accomplishment is running the first 5-second quartermile on a motorcycle, accomplished during an NHRA exhibition run in Houston, Texas, in October, 1999. In the nearly six years since, no other rider has been able to run a “five,” while McBride has done it more than 30 times. At the recent AMA/Prostar Lucas Oil Nationals at McBride’s home track of Virginia Motorsports Park, he set another standard, running five consecutive 5-second runs. His worst run far eclipsed the career best of the entire field. Behind McBride in alltime performances are Ron Webb (6.04), Holland’s Roel Koedam (6.04) and series #2 plate-holder Chris Hand (6.10).

Riding a Top Fuel bike can be a dangerous endeavor. One of the pioneers of the sport, Elmer Trett, lost his life in a 1996 racing accident. Closing in on the 5-second barrier, Trett ran a 6.06 at a Prostar event in Indianapolis. It was the first-ever 6.0second run. Two weeks later during an exhibition at the NHRA U.S. Nationals, Trett inexplicably lost his grip on the bike and came off at the finish line at 232 mph. Since then, McBride always dons an Elmer Trett T-shirt under his leathers in tribute to his mentor. “Elmer always rides with me,” he says.

In another tribute, McBride holds all the performance records except the V%mile speed record, which he has surpassed but refuses to claim, allowing Trett to remain in the record books.

McBride himself suffered a top-end spill, coming off his bike at 205 mph in Gainesville in 1992. He emerged relatively unscathed but it took him and Steve two years to field another bike. “You don’t want to make any mistakes,” says McBride. “I know what can happen.”

The difficulty and expense in building and running a Top Fuel bike keeps their numbers low. There are less than a dozen such machines in the U.S. and maybe 30 worldwide. Currently only the AMA/Prostar series runs competition for Top Fuel motorcycles in the U.S.

Each bike is unique. McBride’s is fashioned around a one-off, 100-inch RaceVisions chassis. The purpose-built engine is a supercharged 15 lOcc inline-Four running on 94 percent nitromethane and produces more than 1500 horsepower with a powerband between 8500 and 10,800 rpm. It has a Vance & Hines-built, Kawasaki-style, two-valve cylinder head developed from a Pro Stock casting. An Autorotor supercharger spins to 16,000 rpm and produces up to 44 pounds of boost. The bottom end is an aftermarket aluminum case that houses the custom crank built by Puma in the U.K. Power is delivered through a 4-inch-wide belt to a two-speed planetary transmission mated to a multi-stage progressive lock-up clutch. A #630 chain turns the 14-inch-wide Mickey Thompson slick.

Steve McBride is responsible for fabricating all the supporting hardware (most notably the exotic progressive clutch), fuel system and tuning. Much of the run is pre-determined in the pits. Application of full throttle (about a quarter-turn) initiates a series of pneumatic timers that control fuel delivery and clutch engagement. The fuel curve varies with track position and the 10 stages of clutch engage progressively until lockup occurs at 4 seconds into the run.

Nitromethane is a load-dependent fuel, meaning more fuel will bum (and more power will be produced) when a load is applied. Tuning-part art, part scienceinvolves getting the right balance of fuel delivery and clutch engagement for the track and atmospheric conditions. Deviate too far from the sweet spot and you will either smoke the tire or lean out and the engine will start to consume itself.

Steve McBride explains, “You keep the horsepower at the right level with the clutch. As the clutch comes to the motor, you add fuel. As you approach terminal speed and the clutch is one-to-one, you take fuel away.”

After reacting to the Christmas tree, McBride has to make one shift and keep the bike straight, which is done by aggressive “crawling” (a technique that earned him the nickname “Spiderman”). Stopping, particularly at shorter tracks, is sometimes the most harrowing part. Dragbikes do not have parachutes like their fourwheeled brethren.

Top Fuel bikes are a visceral experience. They can be seen, heard and unmistakably felt. The visual of the exotic machine carrying the front tire combined with its ear-splitting and unique exhaust note is unforgettable. One of the most thrilling moments in motorcycle racing is watching Spiderman capture a “five.”

Matt Polito

Stoked on Strokers

It’s a sorry state of affairs for old-school motocrossers, but two-strokes have been all but relegated to the history books. At this year’s AMA outdoor season opener at Hangtown in Prairie City, California, not one 125 left the starting gate, all competitors mounted on 250cc four-strokes. And things were hardly any better in the 250CC ranks, as all but the Kawasaki factory team and a small handful of privateers were mounted on 450cc four-strokesand Team Green would assuredly have been on "diesels," too, if the KX45OF were ready.

Seeing as how the words "two-stroke" and "vintage" are becoming ever more c1oseIy associated, Vintage Iron propri etor Rick Doughty did the logical thing and expanded his annual vintage race eekend to become the Vintage & TwoStroke World Championships. Held at Southem California's Glen Helen Race ray this past May, the eighth-annual event Included the traditional vintage classes on Saturday plus vintage and modern `two-stroke classes on Sunday.

Asked why he added the two-strokes to the program. Doughty replied, “It’s an era that we don’t want to see completely disappear. The bikes are cool, and they make cool noises. When you hear a race go off with all two-strokes this weekend, that’s just something you don’t hear at a modem motocross anymore. We just want to keep that alive.

“They’ve had the Four-Stroke World Championships for almost 30 years now, and they started it just as four-strokes were going into obsolescence,” Doughty continued. “Two-strokes are becoming obsolete as we speak, and I thought it may not be a big event now, but we’ll at least get it going and give guys a chance to come out and mix gas and oil and have fun.”

White Bros, founder Tom White obviously wasn’t threatened by this upstart event rivaling his longstanding FourStroke World Championships, as he not only served as track announcer over the weekend but also competed, topping the 250 Intermediate class. Promoter Doughty also threw a leg over a bike “for the first time in six or seven years at one of my events” and topped the Decade Expert class for bikes over 10 years old. Not bad for a couple of old guys.

Offering a slightly longer view of the current scenario was Father Paul "Baz" Boudreau, former editor of Motocross Action and an enthusiastic spectator at Glen Helen. "It's all going back to fourstrokes because the technology is just awesome," says the man who started rac ing on a four-stroke BSA 500 in the 1960s. "You've got all this stuff going on inside the engine which is giving it all kinds of rpm, all kinds of horsepower. The two stroke doesn't have that dynamic." lD~4+l-..~. `+ A~~A

But the two-stroke isn’t dead yet, insists Boudreau’s one-time colleague Brad Zimmerman, former editorial staffer at the late Popular Cycling and Motorcy clist when the latter used to include dirtbikes. "I think if you look at the R&D departments at each of the Japanese man ufacturers, you'd see that their budgets haven't gotten any smaller on the twostroke side," he declares. "I know those guys run seven to 10 years ahead, so I'd say from right now, we'll probably see three, maybe four more generations be fore they stop making two-strokes. Right now it still makes sense to make them because people are still buying them."

Hopefully, word will spread and the 2006 running of the Two-Stroke World Championships will garner the support that it deserves. Old ring-dings never die, they just come out of mothballs to race once a year at Glen Helen.

Whatever the case, rider turnout was light at this year's event, potential com petitors either failing to comprehend that this wasn't just a vintage race or content to spend their Memorial Day weekend elsewhere. Racing celebrities consisted solely of former factory riders Bruce Mc Dougal and Mike Runyard, and the high ly anticipated Pro race attracted just two combatants: former 125cc supercross frontrunner David Pingree and red-headed 17year-old Adam Chatfield, a new arrival from across the pond who intends to con test the AMA outdoor nationals. Ping won the first moto but experienced a mechani cal setback in the second, so handed the win to Chatfield. Actually, there was a third entrant, but Robert Beaupre was mounted on a 1983 Honda CR480, so never stood a chance. He still got a share in the $1000 purse, though! -

Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHauiin'

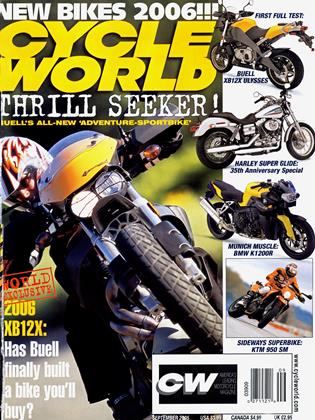

September 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsIn Praise of Cop Bikes

September 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMarket Value

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupFuture Road-Burner Revealed?

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVictory's Jackpot

September 2005 By Calvin Kim