SLIP-SLIDIN' AWAY

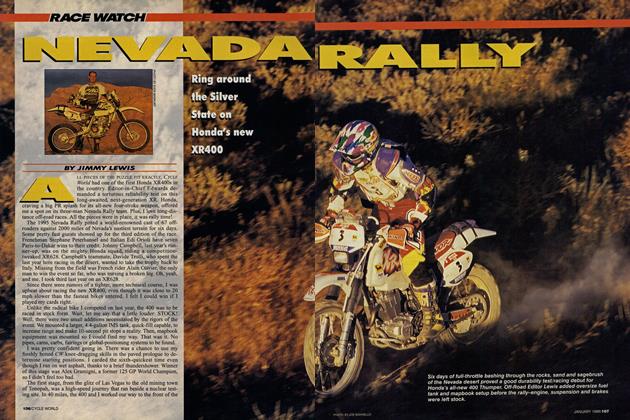

RACE WATCH

Speedway star for a day

SILLY ME. I ALWAYS THOUGHT speedway races were four laps long because spectators have short attention spans. But now, after having spent a day going in circles on an old two-valve Jawa, I know better: It's because that's as long as it's possible to hold your breath.

1 remember going to the California Superbike School for the first time in 1984 and hearing Keith Code extol the virtues of replenishing your respiratory system. “Don’t forget to breathe," Code said, “that’s what the straightaways are for."

Speedway tracks, unlike road courses, don't have any straightaways. At least not the ones in Southern California, and certainly not the diminutive, eighth-mile oval at Ken Maely’s ranch, where fellow Cycle World editors Don Canet and Matthew Miles joined me in an effort to discover The Truth about speedway motorcycles.

Conventional wisdom holds that riding a speedway bike is backwards from anything you’ve ever done on an “ordinary” motorcycle. On a speedway bike, you accelerate going into the corners to get the bike sideways, and back off the throttle coming out in order to hook up. If you’re heading for the crash wall, you're supposed to gas it. Easier said than done, as we would see.

With no provision for electric or kick starting, speedway bikes rely on the tried-and-true method of bumpstarting. The procedure goes like this: Climb aboard, fasten the deadman’s switch around your right wrist, open the two petcocks beneath the small fuel tank, roll the bike backwards until the piston hits top dead center on the compression stroke, then pull in the clutch and have a willing assistant push you off. With luck, they fire on the first attempt.

A speedway motorcycle feels oddly bicycle-like, not only because of its slim width and small solo seat, but because its footpegs are positioned fore and aft like a bicycle’s pedals. There's effectively only one footpeg. a long metal projection positioned aft of the engine on the starboard side. A tiny, rubber-covered footpeg is located on the left frame downtube, and is nigh impossible to find in the time allotted between turns; you just kind of hold your left leg up on the “straights."

Controls consist only of a throttle and a clutch; there's no gearshift and no brakes. Thus you control the bike with a combination of throttle and body English. Approaching a turn, you step forward with your left foot, transferring your weight onto your steel shoe. You then lift your butt off the seat slightly, slide forward toward the oil filler cap on the frame backbone and twist the throttle. As the corner exit approaches, you sit down, modulating the throttle to control traction. With practice, it's possible to get so sideways that the fork turns past 90 degrees, so that the rear wheel is ahead of the front. Not a good time to chop the throttle. The extent to which you're able to “back it in" depends on variables such as track conditions and rider experience.

With no experience, we looked like squids. At first, I teetered around, sliding in short spurts, with Maely yelling at me for doing little more than wearing out one of “his” steel shoes. (The shoe is mine, l paid for it, but Maely takes exceptional pride in his work.)

Speedway engines have a total-loss oiling system, so a bike can only run for a dozen or so laps before it needs its supply of Castrol R replenished. The smaíl supply of methanol in the fuel tank lasts a bit longer. At first, we were dismayed at the prospect of being able to turn only that many laps at a stint. But in reality, none of us could go that long without becoming winded or. more likely, crashing. We lost the front end. the back end. w'e lowsided, we highsided. Associate Editor Miles nearly put himself in orbit during his seventh and final getoff. perhaps taking the term “pilot” a tad too literally.

Regardless, by the end of the day, we all got it down pretty good. I said that morning that I wasn’t going home until I put together a “perfect” lap, so I was delighted when I managed to turn three pretty good circuits during my last riding stint before my attention waned—likely due to oxygen depravation—and I clouted the crashwall, albeit lightly.

The verdict: If speedway racing appeals to you, go for it. The bikes are different, true, but not so different that ordinary riding techniques don't work. As with any form of motorcycling. practice makes perfect.

Well, maybe not perfect.

—Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Norton Girl And Other Tragedies

November 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeNone Dare Call It Progress

November 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsReplacements

November 1991 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUpheavals

November 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1991 -

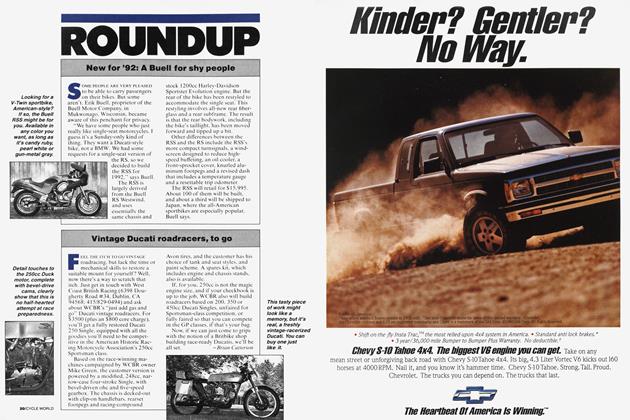

Roundup

RoundupNew For '92: A Buell For Shy People

November 1991