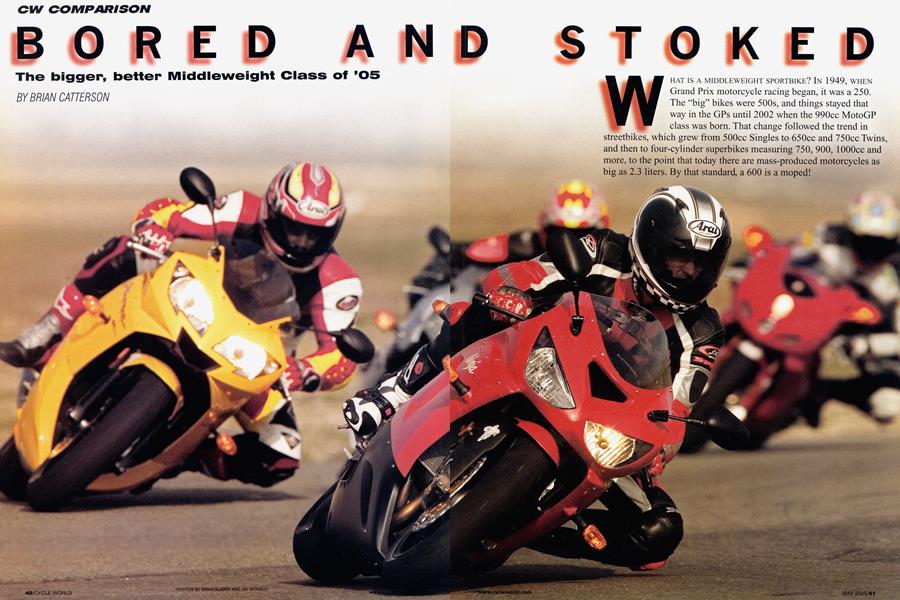

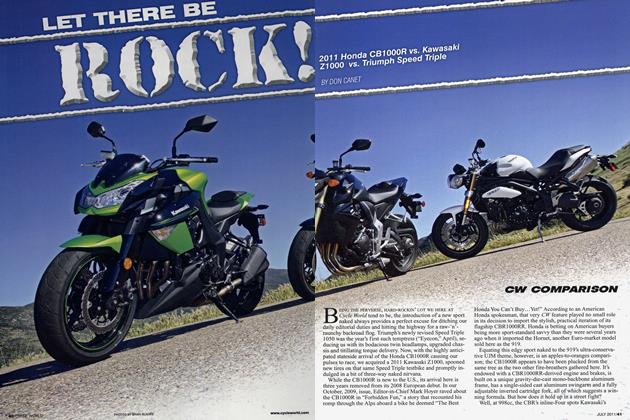

BORED AND STOKED

CW COMPARISON

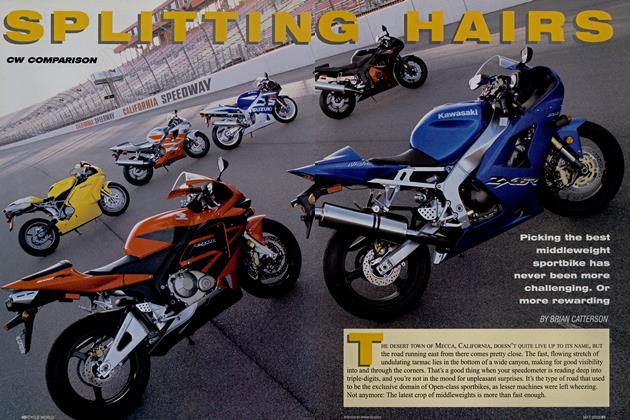

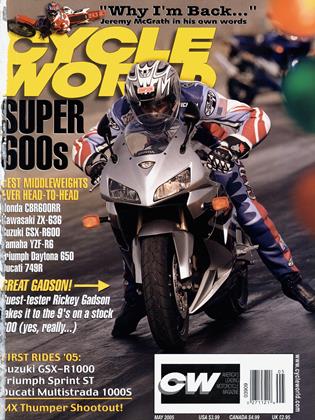

The bigger, better Middleweight Class of ’05

BRIAN CATTERSON

WHAT IS A MIDDLEWEIGHT SPORTBIKE? IN 1949, WHEN Grand Prix motorcycle racing began, it was a 250. The "big" bikes were 500s, and things stayed that way in the GPs until 2002 when the 990cc MotoGP class was born. That change followed the trend in streetbikes, which grew from 500cc Singles to 650cc and 750cc Twins, and then to four-cylinder superbikes measuring 750, 900, 1000cc and more, to the point that today there are mass-produced motorcycles as big as 2.3 liters. By that standard, a 600 is a moped!

There was a lot of talk about displacement during this year’s middleweight sportbike comparison, and even some accusations of cheating, though none of the contenders were illegally altered from stock. Most fingers were pointed at the Kawasaki ZX-6R, which displaces 636cc and is thus ineligible for 600cc Supersport racing. Ditto the Triumph Daytona 650 and Ducati 749R, though the latter, being a V-Twin rather than an inlineFour, was criticized more for the size of its price tag.

We defended our choices by pointing out that this isn’t supposed to be a 600cc Supersport shootout; it’s a comparison of the various middleweight sportbikes available on the market, most of which will be ridden primarily on the street.

That said, could the 600cc sportbike category be moving toward a new, larger displacement limit? It’s possible; back in the 1980s, the Japanese offered sporting 650cc Fours-remember the Nighthawk, KZ, Katana and Seca? Will we eventually see a 650cc sportbike class? Or a return to 750s? Should the Suzuki GSX-R750 have been included in this comparison?

Enough bench racing already. For the racetrack portion of this year’s shootout, we returned to Willow Springs, located an hour north of Los Angeles near the high-desert town of Rosamond. We spent two days there, the first on the tight-and-twisty Streets of Willow and the second at the breathtakingly fast Willow Springs International Raceway. To ensure that the bikes were on even footing, Michelin brought out a tractor-trailerload of tires, fitting Pilot Power “track-day” radiais on the first day and the new Power Race radiais on the second (see sidebar, page 44). To make things even more interesting, we allowed the manufacturers to upgrade their bikes to Supersport spec for the big track, fitting alternate exhausts, ECUs and 1-tooth-smaller-than-stock countershaft sprockets; no suspension mods, though, and no internal tweaks. We then ran them all in stock and modified form on the L&L Motorsports mobile dyno.

After our road course testing was complete, we ventured to Los Angeles County Raceway east of Palmdale for a day of dragstrip testing, with former AMA/Prostar 600cc Supersport dragracing champ Rickey Gadson doing the riding (see sidebar, page 48). That explains the E.T.s being a half-second-quicker than we’re accustomed to seeing-the man is that good. And of course we weighed and measured, poked and prodded all of the bikes, rode them on the street and put them through our usual performance tests. All in the interest of determining which is the class of the Class of ’05.

DUCATI 749R

Twenty-two thousand. That’s the most significant number on the Ducati’s specs sheet, and it unfortunately denotes its price. Yes, folks, you read that right, the 749R costs nearly three times as much as the competition.

Why did we include the thoroughbred 749R instead of one of its less-expensive stablemates? Two reasons:

1 ) Because it was there; why should Ducati be penalized for offering a World Supersport homologation special equipped with racing-quality components? And 2) because the last time we included the more pedestrian 749S in a middleweight sportbike shootout in 2003, it got smoked.

The second most significant number on the Ducati’s specs sheet is its displacement: 749cc, as opposed to the 748cc of the other 749 models. That’s because the 749R has a bigger bore and a shorter stroke, which combined with titanium rods and valves lets it rev higher, quicker. It also boasts a slipper clutch and a deep, V-shaped oil sump, the better to prevent the pump from sucking air under high g-loads. Last year’s 749R had a carbon-fiber fairing, but this year’s is plastic, which cuts down on costs but eliminates one of our favorite details: the black weave showing through the unpainted logos.

Not surprisingly, given its 150cc displacement advantage, the Ducati made the most horsepower in this group, nearly 113 in stock trim and 3 more with a Ducati Performance ECU and Termignoni pipe. As well as the most torque, 10 more than the second-best Kawasaki, which helped it clock the quickest top-gear roll-on times. It also posted the highest top speed: 165 mph.

That added grunt proved advantageous on the street, where combined with exceptional throttle response it gave the rider a choice of gears, much like an Open-classer. And it should have been an advantage on Willow’s Streets, but unfortunately the 749’s stock final gearing is so tall, and thus the gap between its ratios so wide, that it often felt “between gears.” Our only other motor-related gripe concerns the tooabrupt rev-limiter, which shuts the party down nanoseconds after the shift light illuminates-a trait that bothered Gadson at the dragstrip, too.

Fortunately, the 749R handles fabulously, with a luxurious ride from its Swedish Öhlins suspension and unparal-

leled front-end feedback. Though the Italian bike weighs some 30 pounds more than its Japanese peers, it doesn’t feel that much heavier, and its superb Brembo radial brakes let you stop on a dime-or trail-brake around the edge of one. Steering is neutral but fairly heavy, which we could have lightened up by steepening the adjustable steering head, but that would have compromised stability, which is one of the Ducati’s greatest strengths. Most of our testers also praised the bike’s “limitless” cornering clearance until ace Road Test Editor Don Canet brought the bike back to the pits with the fairing scraped on the right and the shift lever bent around backward on the left! (His photo should adorn a Wheaties box soon.) Having crashed a 749R when that happened in

last summer’s MasterBike competition (CW, September), Canet wisely parked the Ducati, which largely explains its lackluster lap times.

For most of us, though, riding the 749R was sheer joy.

But all of its plusses must be weighed against its one major minus-that price tag. Said Feature Editor Mark Hoyer,

“Unless I were to seriously go racing, I can’t see investing $22,000 in a track-day bike. The riding pleasure is high, but the crashing pain that could possibly be inflicted upon my wallet means I would reluctantly choose another bike.

Or three...”

HONDA CBR600RR

Ah, Old Faithful, the benchmark for modern middleweights. For years, we’ve rambled on about how friendly the CBR is, once going so far as to christen it the “Labrador Retriever of Sportbikes.” Our last testbike was even the right color.

Well, our latest one is silver, not black. But is it good enough for gold?

While not as comfy as the F4i that preceded it (still available for $8499, incidentally), the RR is nonetheless among the plushest street rides of this group, second only to the couch-like Triumph. Control feel is excellent; it’s as though Honda’s R&D engineers examined every man/machine interface and fine-tuned them for maximum ergonomic efficiency. Probably because they did. The fuel tank is a bit fat by current standards, spreading the rider’s legs farther apart than on the waifish Ducati or Yamaha; and the seat is high, the bars and windscreen low. But aside from those nitpicks, life is good on the CBR on the street.

It also does quite well on the racetrack, thank you very much. Benefiting from a recent Slim-Fast diet, the Honda’s weight is now on par with the Kawasaki and Suzuki, though still a few pounds heavier than the class flyweight, Yamaha’s R6. And thanks in part to a new Showa inverted fork and Tokico radial front brakes, the CBR now handles much like the Ducati: solid and stable (in spite of having the shortest wheelbase), with neutral but slightly heavy steering. It definitely turns-in quicker than before. You sit closer to the bars on the CBR than on the 749, though, and more on top of the bike rather than down inside. It’s a tidy package that traces its layout to the RC21IV MotoGP racer.

Even at the bumpy Streets, the Honda proved unflappable, a trait that helped it post the second-quickest lap time there in spite of having the least-powerful engine. Its engine performance improved considerably on day two with the addition of an Erion Racing titanium pipe and HRC ECU, leapfrogging ahead of the Suzuki and Triumph. So equipped, it tied the Kawasaki for the biggest increase with a gain of 4.1 hp (yes, the days of double-digit power gains are long gone) and turned the second-quickest time at the big track, too.

Stock or modified, the Honda’s engine is a screamer, making peak power at higher revs (13,500 rpm) than any other bike in this test. Power then tails off to the 15K redline, which begs the question: Why does the shift light illuminate at 15K? It really ought to come on closer to the power peak.

While it obviously isn’t as exotic as the Ducati, the Honda exudes the same quality, and that quality comes at a price: $8999, making it the second most expensive bike of this lot. But according to a company spokesman, Honda was just the first to raise its prices in response to an unfavorable dollaryen exchange rate; he suspects the others will follow suit. In more ways than one, if they’re smart.

KAWASAKI ZX-6R

The 636cc ZX-6R almost won this shootout when it was introduced two years ago, thanks in large part to That Motor; remember, Tommy Hayden won 750cc Supersport nationals on a factory-backed 636. What held it back in stock trim was its handling, the main problem being poor small-bump absorption that made the bike nervous when leaned over on rippled pavement. So when we heard that the 2005 version had Showa suspenders instead of the previous Kayaba units, we were ready to send the trophy to the engraver even before the bike had arrived.

Good thing we didn’t, then. Not that the Kawi isn’t in the running, because it most assuredly is. Particularly at the dragstrip, where it stomped the others with a scorching 10.3-second pass at 132 mph. “Let me just say that I do not work for Kawasaki anymore,” gushed dragracer Gadson,

“but Kawasaki has done it again.” Rickey clearly appreciated the extra cubes as he noted that the “cheater” 636 and the Triumph Daytona 650 were the only bikes that power-wheelied at the top of first gear.

The ZX-6R was thoroughly revised for 2005 in an effort to improve its previous shortcomings. Its seating position was improved through higher bars, a flatter seat and less-rearset foopegs, making for a more comfortable riding experience, particularly for taller riders. And mechanically, the bike gained the aforementioned Showa suspenders, “petal-style” brake discs (what everyone else calls “wave” rotors), a more aerodynamic fairing and underseat muffler. It also got the slipper clutch from the Supersport-legal 600cc ZX-6RR, and motor upgrades that helped boost hp to 112 in stock trim, and 116 with a Kawasaki Racing ECU and Akrapovic exhaust-the best of the Fours.

The 63 6’s motor held it in good stead not just at the dragstrip, but on the roadrace track, too-we’re talking 750 levels of acceleration here. You’d think with its extra 37cc of displacement the ZX-6R would be a torquer, and it is, grunting out a greater number of foot-pounds than all but the Ducati. And you’d think that torque would give it the grunt to squirt from corner to corner at the Streets, and you’d be partly right; all that power arriving abruptly at low revs tended to unsettle the chassis, the front end going light and heading toward the outside of the corner.

While we’re on our soapbox, we’ll point out that the engine is still pretty buzzy, and we’ve never cared for the hard-to-read digital tachometer.

Having said that, Canet managed to turn the third-quickest lap at the big track on the Kawasaki-then filed for hazardous-duty pay! The problem was instability, the bike threatening to break into a tankslapper while accelerating up the hill from Turn 3 to 4, while cresting Turn 6 and while running over the bumps in 145-mph Turn 8. We tried reducing preload and softening up the damping, but the twitchiness never went away.

Hoyer echoed Canet’s findings, saying, “I liked the amount of information from the chassis, just not what the front end was telling me.”

Like its bigger brother the ZX-10R, the ZX-6R would benefit from a steering damper. With one, this bike could be a winner. Without one, it’s a wild ride-and not necessarily in a good way.

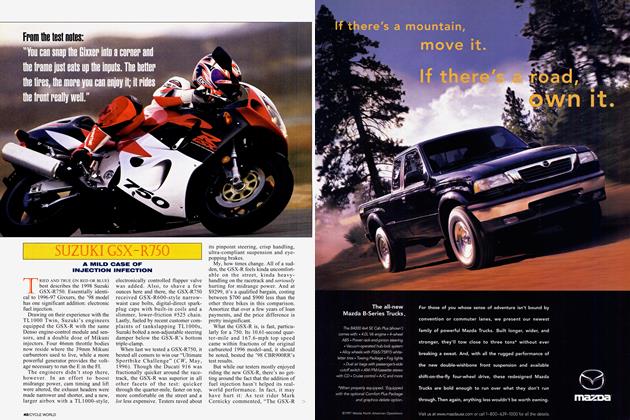

SUZUKI GSX-R600

After reading a rough draft of my Honda CBR600RR test a couple of issues ago, Canet burst into my office and said, “Suzuki isn’t the defending champion, Yamaha is.” Which would have been true if I’d been referring to AMA Supersport racing, but I was talking about our 2004 middleweight sportbike comparison.

Seeing as how some readers might have drawn the same conclusion, I re-wrote the sentence. But it just goes to show how closely these bikes are associated with racing.

The GSX-R did win last year’s shootout, not to mention Best Middleweight Streetbike honors in our annual Ten Best Bikes competition. It returns to defend its title largely unchanged-though there is a special GSX-R 20th Anniversary Edition model that sells for $400 more.

Where the Honda sets the standard on the street, the Suzuki does so on the racetrack. Ride any year GSX-R600 and then ride the 2005 model, and the family resemblance apparent. It just feels familiar.

The GSX-R has a nicely padded seat, but that’s where its creature comforts end-and Canet said he’d gladly give that up to gain additional feedback through the all-important seat-seat juncture. Beyond that, its racing intent is obvious, with purposeful ergonomics that position the rider’s torso low and forward, his helmet behind the bubble. You definitely sit “in” this one.

The GSX-R’s engine is as invigorating as ever, cranking out an even 103 hp in stock trim, and 104 and change with a Yoshimura EMS and Tri-Oval titanium-and-carbon pipe. It’s a willing performer, eager to rev, and it shifts nicely, too.

“I think the Suzuki has the best motor,” opined Online Editor Calvin Kim. “It’s so smooth and easy that even when it’s strung-out, it doesn’t seem like it is.”

Handling is typical GSX-R, composed, stable and impervious to bumps, thanks in part to the standard steering damper-the only bike aside from the 749 to be so equipped. Feel from the Tokico radial brakes rivals that of the Ducati, encouraging trail-braking all the way to the apex. The suspension, though, garnered mixed reviews, particularly the fork and particularly at the big track. Polar opposite of the Kawasaki, the Suzuki’s stock fork settings were way too soft, and even after we cranked up the compression and rebound damping, the springs still felt flaccid. Where the Honda would suck up bumps in one quick gulp, the GSX-R seemed to take two or more swallows to regain itself.

“Lots of guys base their purchases on dragstrip numbers. If you tell them Don Canet went 1:27 at Willow Springs, they won’t have a clue what you’re talking about. They have no reference point. Only the West Coast loves the turns. The East Coast is all about drag racing. I have five tracks—NHRAquality facilities—within an hour of my house. We race every night but Monday.” —Rickey Gadson

Yet even with this slight issue, the GSX-R set fast time at the big track and edged the ZX-6R for third place at the Streets-by just .04 of a second. Further proof of how close these two bikes are can be seen in their identical top speeds (163 mph) and dry weights (401 pounds).

Oh well, if the past is any indication, next year the GSX-R600 will be all-new again, with a better chance of recapturing its title. Such is the pace of 600-class development.

TRIUMPH DAYTONA 650

Triumph seems to have trouble hitting a moving target. When the TT600 debuted in 2000, it was on pace right up until that year’s new Japanese models came out. Ditto the Daytona 600 in 2003 Now that the British company has acknowledged that the D6 isn’t going to win any Supersport races, it’s free to seek the missing power in the time-honored fashion: through displacement, the new 650 receiving a 3.1mm longer stroke to arrive at its 646cc.

While not a large bike by any stretch of the imagination, the Daytona nonetheless feels more substantial than its peers. This showed on the scales, where it was the heftiest of the Fours, 14 pounds heavier than the Honda with an empty fuel tank, though still 16 pounds lighter than the Ducati.

The Triumph feels different from the moment you turn on the ignition key-and wonder why nothing happens. It’s only when you toggle the killswitch to Run that the dash comes to life, and it’s a few more moments before the starter motor starts to spin.

Once under way, the Triumph impresses with its tractable engine. We had great fun riding the wave of torque, which let it post respectable top-gear roll-on numbers. Engine noise is a growly combination of intake honk and gear whine, and the bike power-wheelies in first gear like an Open-classer. Nice! With no full exhaust system in its accessory line, Triumph went with a slip-on muffler and remapped ECU at the big track and gained just 1.8 hp.

While we loved the Daytona’s engine, its transmission isn’t as praiseworthy. You feel neutral as you shift from first to second-though that doesn’t make it any easier to find at a standstill-and all changes are fairly notchy.

On a positive note, the riding position is the nicest of this lot on the street, more upright than the others even if the fat

fuel tank splays the rider’s legs. The seat is nice and soft, though, and the tachometer is nice and legible.

While the Triumph shined on the street, it came up short on the racetrack, where most testers found it too soft and cumbersome to go fast on. The only bike with a “right-sideup” fork, its handling is a half-step behind the competition. Ditto its non-radial brakes, which had less feel and stopping power, too. Combined, these made riders reluctant to carry as much corner speed, so in addition to braking earlier, they also wanted to brake more.

Even so, the majority of our testers enjoyed their time on the Triumph, their notes peppered with variations on “nice at eight-tenths.” Said Kim, “It’s a fantastic streetbike, in fact the most street-friendly machine here. I can see people wanting to own one now. But in this company of guillotine deathinspired race machines, it’s a little lacking.”

That still didn’t hold back Canet, who managed to turn laps on the Triumph that were roughly 1.5 seconds off fast time at both venues. But then, he used to race a Suzuki Katana...

Kudos to the Brits for staying in the game, offering the most distinctive (and distinguished?) four-cylinder machine in this class, at the lowest price: $7999. If you want to stand out in a crowd, look no farther.

YAMAHA YZF-R6

Which brings us to our final contestant, the R6. Like the Honda and Kawasaki, the Yamaha was thoroughly upgraded this year, gaining an R1-style inverted fork with radial brakes, a taller 70-series front tire (in place of the low-profile 65-series it had before) and revised rear suspension linkage, plus various changes to the induction system aimed at boosting power and improving throttle response.

The engine upgrades obviously work, as the R6 made an even 108 horsepower stock, and 109-plus with a Dynojet Power Commander and the GYT-R exhaust from Jamie Hacking’s racebike-the most of the Supersport-legal 600s. Said Gadson after a 132-mph pass, “Look at the mile per hour-this bike is making horsepower. The only thing holding it back is its light front end.”

Though the R6 feels weak down low, it still drives off of comers, building progressively more power as the revs climb through the midrange toward the 13,100-rpm power peak. And it’s fast: 164 mph on top, 1 mph better than the other three Japanese machines and just 1 mph shy of the leading Ducati.

While the transmission feels a little clunky, we never missed a shift, and reveled in the bike’s tendency to loft its front wheel after high-rpm gear changes in the first three gears. While there’s little need to rev the motor to its 15,500rpm redline, we often found ourselves doing it just to hear it scream. The howl is intoxicating, the perfect racetrack soundtrack.

As nice as the R6’s engine is, however, it’s the chassis that really shines. Handling is edgy and nervous, and borderline twitchy-but only borderline. A steering damper wouldn’t hurt, but you could live without one. Turn-in is quick, and the bike is surefooted in corners. Braking is higher-effort than on most of the other middleweights, but feel from the front tire rivals that of the Ducati. It’s become a cliché, but you feel like you’re holding the front axle in your fingertips.

Given the R6’s light handling and small stature, riding it reminds us of a 250cc GP bike. Said Assistant Editor Mark Cernicky, who used to race a TZ250, “I love the way this bike goes-effortlessly. It disappears beneath you, like the bumps into its chassis.”

Those characteristics helped the Yamaha post the best lap time at the Streets, fully a half-second quicker than the second-placed Honda. And while it was fourth-quickest at the big track, it came within a tenth of the second-place Honda and third-place Kawasaki, just four-tenths off the winning Suzuki. But more telling was the fact that of our six testers, no fewer than five set their best time at the Streets on the Yamaha.

If it’s beginning to sound like we’ve got a winner, well, yes we do. As it did two years ago at California Speedway, the Yamaha stealthily went about its business, earning accolades in virtually every category and nary a complaint. It may be “just” a 600, but it’s the best 600. And the best middleweight sportbike of 2005.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue