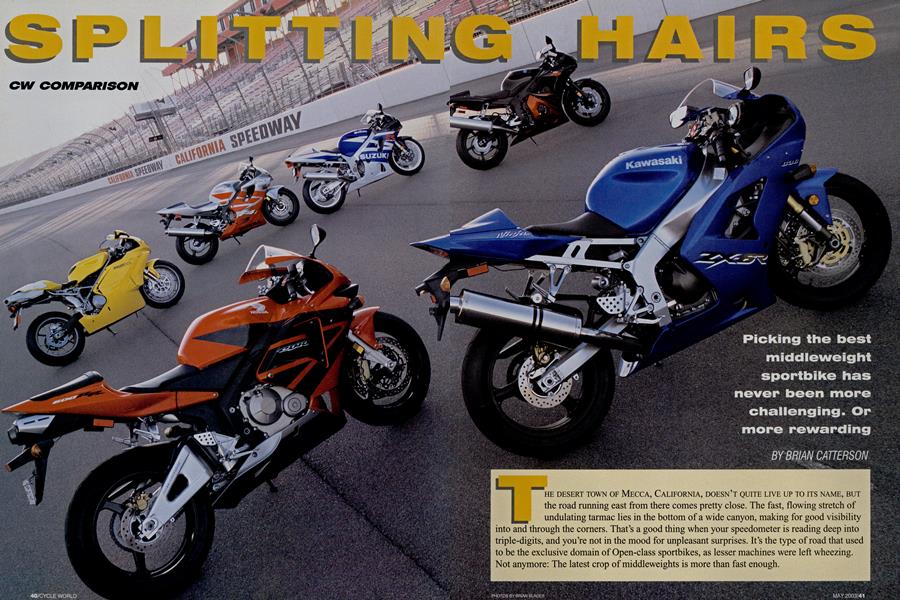

SPLITTIN G HAIRS

CW COMPARISON

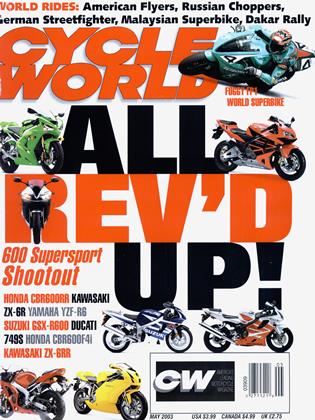

Picking the best middleweight sportbike has never been more challenging. Or more rewarding

BRIAN CATTERSON

THE DESERT TOWN OF MECCA, CALIFONIA, DOESN'T QUITE LIVE UP TO ITS NAME, BUT the road running east from there comes pretty close The fast, flowing stretch of undulating tarmac lies in the bottom of a wide canyon, making for good visibility into and through the corners. That's a good thing when your speedometer is reading deep into triple-digits, and you're not in the mood for unpleasant surprises. It's the type of road that used to be the exclusive domain of Open-class sportbikes, as lesser machines were left wheezing. Not anymore: The latest crop of middleweights is more than fast enough.

How fast? Try mid-10-second quarter-miles and top speeds approaching 160 mph. And on the roadrace track, showroom-stock save for race-compound tires, these street-legal motorcycles are capable of lapping within 5 percent of the best times set by professional racers on factory-prepped Supersport machines, and within 10 percent of full-blown, 180-horsepower Superbikes. Clearly, there has never been a better time to be in the market for a middleweight sportbike.

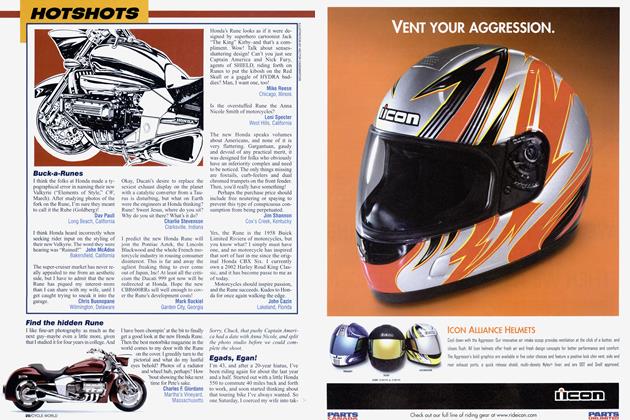

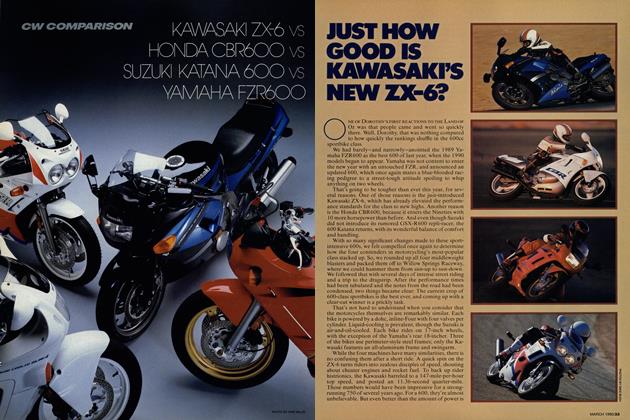

To determine which one of these highly honed haulers is best, we gathered together five 600cc Fours-the new Honda CBR600RR, holdover Honda CBR600F4Í, Kawasaki ZX6R, Suzuki GSX-R600 and Yamaha YZF-R6-plus the V-Twin Ducati 749S, by rule, legal for both AMA and World Supersport racing. We also requested a limited-production Kawasaki ZX-6RR, but were only allowed to test it at the racetrack; without any street miles, it was thus relegated to sidebar status (see page 54).

Testing began with an overnight street ride to our familiar stomping grounds of Borrego Springs in the desert northeast of San Diego. From there we headed to our top-secret top-speed testing site, and then, some 600 miles later, to California Speedway in Fontana for a day’s dragstrip testing followed by a day on the AMA National roadrace course. The latter came on the heels of a two-day factory-team test, so the track was in as good shape as it could possibly be, with lots of rubber laid down and haybales in all the right places. In order to make the most of our track time, we shod each of the bikes with Pirelli Supercorsa radiais in SC 1 soft front and SC2 medium rear compounds, and also outfit each with onboard data acquisition from Kinetic Analysis (www.kineticanalysis.com).

The first thing you need to know about these bikes is that even the longest-in-tooth is still incredibly capable. Right from the start, the Honda CBR600F4Íintroduced in carbureted form way back in 1999 before being upgraded with fuel-injection in 2001-was praised for its comfortable riding position and easy handling. Though its 86horsepower engine gives away 18 ponies to the hottest new 600s, it never feels slow on the street, and only felt a little anemic accelerating onto the California Speedway banking.

For most of our testers, riding the “old” Honda was like coming home again. More than any other motorcycle, the F4i has come to represent the sportbike yardstick-or maybe, considering that it’s “just” a 600, the sportbike ruler. If it were a canine, it would be a big, friendly, floppy-eared Labrador Retriever, anxious to fetch balls until its tongue was in full pant. Or yours, whichever came first.

The F4i’s only shortcomings on the racetrack are a side-effect of the very things that make it so good on the street. Its relatively low footpegs drag early and often, along with the rightside muffler canister when things really heat up. And its high handlebars, while affording significantly more leverage than the other bikes’ lower clip-ons, can sometimes let you feed in a bit too much input, which gets things waggling. But at real-world speeds, in the hands of real-world riders, it’s a model 600cc citizen, and for most buyers would still be the most rational purchase. It’d just be a hard sell convincing folks of that fact in the face of the racier, sexier competition.

The latest evolution of Suzuki’s GSXR600 was introduced in 2001, and has remained largely unchanged since. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, as Aaron Yates’ 2002 AMA Supersport Championship on the works Yoshimura Suzuki attests.

Like the F4i, the GSX-R feels immediately familiar, a sensation strengthened by the familial resemblance to its bigger brothers, the GSX-R750 and 1000. Compared to the other bikes in this test, the Suzuki feels large, with a wide gas tank and relatively spread-out riding position. How so? Because everything else has shrunk. With its extreme riding position, it’s the least comfortable on the street, albeit by a narrow margin. What it does have is the most protective fairing of the bunch. In fact, on a blustery day in the desert, the GSX-R posted the highest average top speed, its slightly slower radar-gun reading with a tailwind assist more than offset by its higher reading fighting a headwind in the opposite direction.

On the racetrack, the GSX-R displayed a number of strengths, paramount among them stability. Along with the Ducati (which not coincidentally is the only other bike that comes stock with a steering damper), it didn’t show a hint of uneasiness while negotiating the bump in California Speedway’s 100-mph infield chicane (Turns 10/11 on the accompanying map). That composed feeling let it rail through the two high-speed sweepers at either end of the infield as fast as anything else, yet it still got through the chicanes plenty quick, even if changing direction took more effort than on the other bikes.

The Suzuki’s engine sounds the most menacing of the Fours, with a meaty growl at low revs that transforms into a banshee wail at high rpm. It also has the most noticeable step in its powerband, coming “on-song” like an old two-stroke as it nears redline. Yet even so, it drives nicely off of corners, its rear tire never threatening a sudden break in traction. Or maybe the relatively thickly padded seat just prevented us from feeling the tire breaking loose. The GSX-R possesses more engine braking than the other Fours, though, which means you have to be careful while downshifting or risk inducing rear-wheel hop.

A couple of testers noted missed shifts, one mentioned that his boot heels hung up on the tailsection, and another commented that his feet kept slipping off the footpegs. But because these weren’t widespread complaints, chalk them up to individual preference.

The GSX-R’s biggest problem, however, has nothing to do with its performance: Compared to the more stylized, rakish competition, it just looks dated.

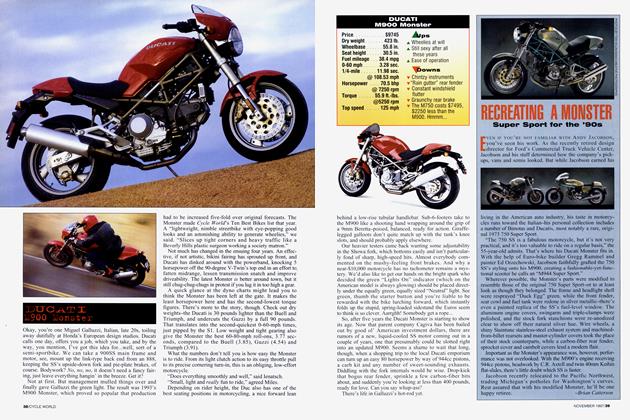

Can’t say that about the new Ducati 749S, whose controversial lines (shared with its bigger bro, the 999) somehow look even better in yellow. There’s more to the two bikes than a similar appearance, however, as the 749S essentially is a 999 with a smaller-displacement engine, which means it weighs 50-60 pounds more than the 600cc Fours.

Fortunately, that weight isn’t noticeable anywhere except in the garage. You’d expect to feel the difference under braking, but the 749S’s superb four-pad Brembos let it stop with the best of them.

The 749’s “S” suffix means that it has been upgraded compared to the base model, wearing among other things a lightweight aluminum subframe. Sorry to say, then, that said subframe flexed disturbingly on bumpy backroads, even under our lighter testers.

Everyone was anxious to ride the Ducati on the street, and as we found with the 999, the 749 is indeed more comfortable than the 748 it replaces. Or make that less uncomfortable, because it’s still a bit of a rack, even if the flatter, more spacious seat means you now carry less weight on your wrists. The suspension is also noticeably more supple on the street than before, without any tradeoff on the racetrack. It ranks near the top overall.

The 96-horse V-Twin gives away a few ponies to the strongest-running Fours, and in spite of having a nice, wide powerband, its rev ceiling-thousands of rpm lower than that of the 600s-means you need to shift more often. And you have to be careful not to get into the rev-limiter, because the ignition cuts out so abruptly that you could conceivably lose the front end if you were leaned over at the time.

The torquey 749 does drive off low-speed corners really well, though, its close-ratio transmission giving it a gear for every occasion, and letting it accelerate where most of the 600s are waiting to get into the meat of their powerbands. But the tranny’s tall first and short sixth gears hindered both dragstrip performance and top speed numbers, both slowest in this test.

Worse, our 749’s engine started to glisten with oil during our street ride, which we initially attributed to blow-by through the crankcase breather (our 999 did the same thing).

But when on the morning of our racetrack test lubricant began to visibly seep past the vertical cylinder’s valve-cover gasket onto the shock absorber and rear tire, we were forced to park the bike and make a frantic phone call to Ducati North America-ironically, the only company that had declined our invitation to have a technician present at our test. To his credit, new PR maven Joey Madrigal got busy on the phone, and by early afternoon had arranged for the folks from Spectrum Honda/Ducati in Irvine to deliver a replacement 749S. Downside was that the replacement bike, besides needing Pirellis mounted, had zero miles on the odometer, so we lost time performing a gentle “break-in” on it before ace Road Test Editor Don Canet climbed aboard for one brief session late in the afternoon. So the Ducati’s status as the slowest bike around the racetrack may not be entirely deserved. But even with more time on the bike, no way it’s a threat to the top three at Fontana.

A bigger issue, though, is whether buyers are willing to pay a premium-a whopping $6000 more than the 600s-for this bike, never mind the questionable reliability, which (hopefully) was an isolated case.

The other “cheater” bike in this largely 599cc grouping is the new Kawasaki ZX-6R, bored and stroked to 636cc. Those extra 37cc make for a > way bigger difference than you’d expect, as the engine produces noticeably more midrange torque than the other 600s and, with 104 bhp at the rear wheel, the most peak power of this group. The former translated into harder lunges out of California Speedway’s slower infield comers, and let us skip a downshift or mn a gear taller in places. Clearly, the bike has motor; more than one tester got off jabbering about 750-class performance. It still revs like a 600, however, its 15,500-rpm redline and soft rev-limiter encouraging frequent trips to the mechanical stratosphere. Can’t say we appreciate the LCD rev-counter, though; like the one on Honda’s RC51, it’s too hard to discern at a quick glance. Good thing there’s a shift light.

The Kawi’s understated (yet attractive) solid-blue paint made us think it would be a middle-of-the-road streetbike, like its forebears or the Honda F4i. The joke was on us: This thing’s as hard-edged as anything else in its class. It’s still fairly comfortable, however, ranking near the top of this group.

In terms of high-tech, Kawasaki one-upped everyone else this year by outfitting the 6R with a stout inverted Kayaba 41mm fork equipped with radially mounted quad-pad Tokico calipers. The new brakes offer superb stopping power, but unfortunately don’t offer much in the way of feel; maybe a change in brake pad material would help?

Like many Kawasakis we’ve tested over the years, our ZX-6R came with its steering-head nut torqued down so tightly that the bike felt like it was wearing a steering damper. Of course, it wasn’t, and this sticki> ness simply inhibited the front wheel’s ability to “find center,” the very function trail is meant to perform. With its stem too tight, the 6R’s chassis displayed worrisome weave and wobble. And when we had a Kawasaki tech loosen things up at the racetrack, we experienced the opposite effect, the front end breaking into big tankslappers through the fast infield chicane. A proper steering damper would work wonders.

A bigger issue is the 6R’s suspension, which suffers from excessive compression damping at both ends. This hinders ride quality over small ripples and squareedged bumps-just the type of obstacles you encounter on the street. And it was bothersome at the racetrack, too, making for a flighty front-end feel in the two highspeed sweepers and a tendency to buck fore-and-aft over the bumps leading across the speedway apron onto the trioval. Softening up compression helped but didn’t entirely alleviate the problem. Too bad, because if the ZX-6R had a chassis to match its engine, the conclusion to this test might be different.

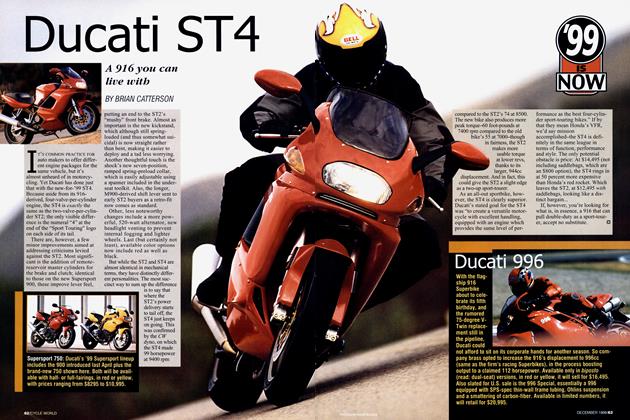

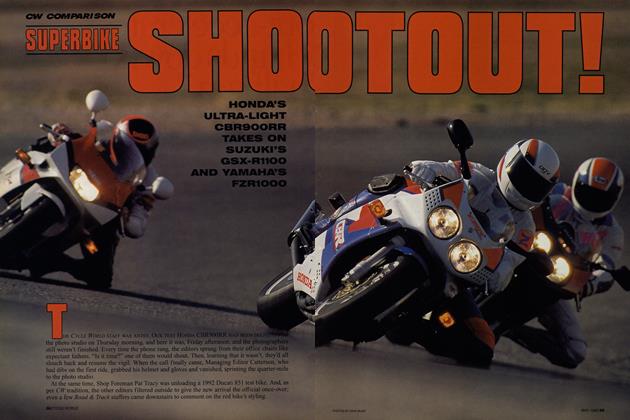

Like Kawasaki, Honda has for years produced nice, rounded street-biased 600s that inexplicably managed to win AMA Supersport Championships-something to do with that Miguel Duhamel fellow. This year, however, Big Red finally got really serious, tapping into the RC21IV MotoGP bike’s bag of tricks to produce a bonafide CBR600RR. Stunning in red and black, the RR was the most anticipated ride in this comparison, and for the most part lived up to its hype.

Like virtually every other Honda, the RR’s fit and finish are first-rate, and its controls possess that “justright” feel. The engine is extremely smooth running-far less coarse than the F4i or ZX-6R, for example-and brake, clutch and gearbox action are excellent.

Oddly, the RR’s stature invoked conflicting comments. Taller riders remarked how compact the bike > was, saying that they felt cramped by the tight bar/seat/peg relationship. Shorter riders, on the other hand, remarked that the fuel tank felt wide, which gave the RR a big-bike feel.

Go figure.

What we do know is that the Honda has steam. Despite giving away 37cc to the Kawasaki, its engine produces nearly identical peak power. Ditto top speed, where it equaled the Kawi and fell just 1 mph shy of the leading Suzuki. The RR did turn the quickest quarter-mile time, however, setting a new CW middleweight record in the process. It was fastest at the end of Fontana’s long straightaways, too, as the accompanying chart (see page 44) attests.

With its muffler tucked up under the tailsection a la Ducati, the Honda has virtually limitless cornering clearance; the only things that touched down were our toe sliders. Stability, too, is at the top of the class, right up there with the >

GSX-R and 749S. The RR was the only bike without a steering damper that could be fully trusted through the highspeed infield chicane, and was the least upset by the bumps leading onto the tri-oval.

While not the quickest bike around the racetrack, the RR came a very close second, and likely could have gone quicker if it hadn’t been hindered by its stock gearing; it felt like it was out of its powerband exiting the numerous second-gear infield comers.

But the complaint most often voiced by our testers concerned the RR’s tendencies to resist turning on the brakes and to mn wide exiting comers. This may have been caused by the Pirelli tires we fit for the racetrack portion of our test, but considering that none of the other bikes suffered the same consequence, probably not.

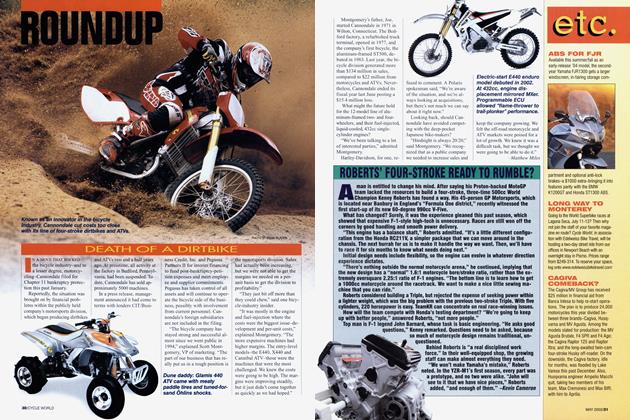

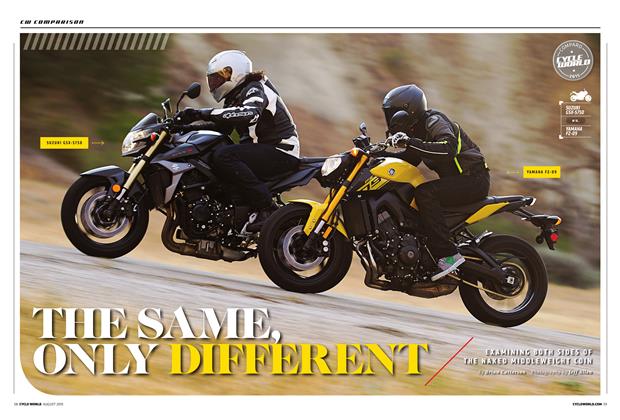

Which leaves the Yamaha YZF-R6. Upgraded this year with fuel-injection and an all-new chassis, the smooth-running R6 was easy to overlook, especially in our testbike’s black-with-red-flames “special edition” (for which buyers will pay a $100 premium). But when one tester after another climbed off the bike singing its praises, everyone began to pay closer attention.

The R6 has always been fast, but this year it’s even more so, cranking out 101 rear-wheel horsepower, storming through the quarter-mile just .16-second slower than the CBR600RR and falling just 1 mph shy of the GSX-R in top speed. Which is a polite way of saying that while it Ó didn’t set any records, it was right there in every category. The fuel-injection on all of these bikes works wonderfully, but the Yamaha’s R1-derived “sensual” system is best of all-absolutely transparent, like a set of perfectly jetted carburetors, without any of the “digital” feel that plagues some other injected bikes. This throttle precision let our testers get the power on sooner exiting comers, which paid dividends down the following straights-particularly when they were able to take advantage of the engine’s 15,500-rpm overrev capability and carry one gear in places where other bikes had to be shifted up and then back down.

It’s going into comers, however, where the Yamaha really shines. More than any other bike here, the R6 encourages deep braking, its superb front-end and lever feel letting the rider trail-brake right up to the point where his knee touches down. The fun continues through the comer, as well, as the sure-footed chassis and superbly sorted suspension let him carry more speed through the apex than on any other bike here. Yet despite its racy nature, the R6 ranks second to the F4i in street comfort.

Previous-generation R6s were pretty on-edge, chassiswise, their steep rake and minimal trail making for a lively ride. But with the changes to the 2003 model’s Deltabox III chassis, the Yamaha is now much more composed. Moreover, its narrow mid-section made easy work of Fontana’s many flip/flop transitions, and while the minimalist windscreen doesn’t offer much protection, it also doesn’t intrude upon your field of vision; with the bike barely noticeable beneath you, you get the feeling you’re flying.

DUCATI

749S

$14.795

HONDA

CBR600F4i

$8199

HONDA

CBR600RR

$8599

KAWASAKI

ZX-6R

$7999

Probably because you are: When all was said and done at California Speedway, the data revealed that six of our seven testers had posted their quickest lap times aboard the Yamaha, making it the undisputed racetrack champion. But more impressively, perusing their notes revealed not a single negative comment; take that to mean the R6 is as perfect as a middleweight sportbike can get. In a class where performance is separated by mere decimal points, that’s what it takes to be a winner. □

SUZUKI

GSX-R600

$7999

YAMAHA

YZF-R6

$8099

View Full Issue

View Full Issue