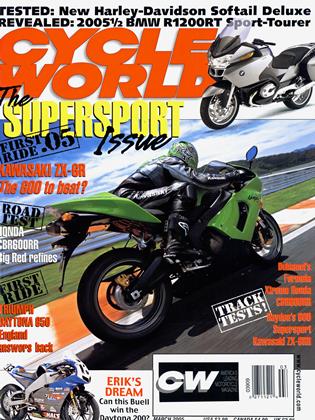

GOING TO THE XTREME

RACE WATCH

Buell is racing for more than wins

STEVE ANDERSON

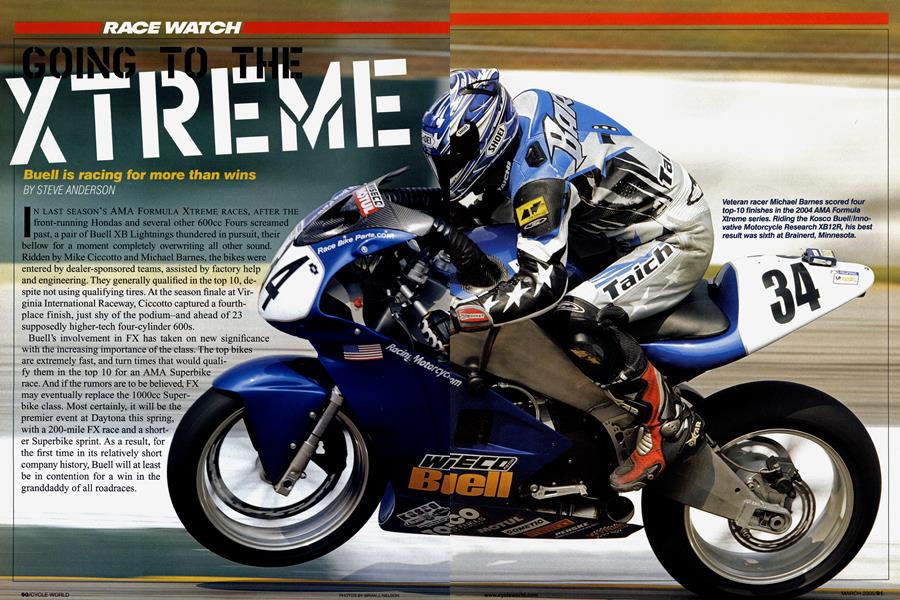

IN LAST SEASON'S AMA FORMULA XTREME RACES, AFTER THE front-running Hondas and several other 600cc Fours screamed past, a pair of Buell XB Lightnings thundered in pursuit, their bellow for a moment completely overwriting all other sound. Ridden by Mike Ciccotto and Michael Barnes, the bikes were entered by dealer-sponsored teams, assisted by factory help and engineering. They generally qualified in the top 10, despite not using qualifying tires. At the season finale at Virginia International Raceway, Ciccotto captured a fourthplace finish, just shy of the podium-and ahead of 23 supposedly higher-tech four-cylinder 600s.

Buell’s involvement in FX has taken on new significance with the increasing importance of the class. The top bikes are extremely fast, and turn times that would qualify them in the top 10 for an AMA Superbike race. And if the rumors are to be believed, FX may eventually replace the lOOOcc Superbike class. Most certainly, it will be the premier event at Daytona this spring, with a 200-mile FX race and a short er Superbike sprint. As a result, for the first time in its relatively short company history, Buell will at least be in contention for a win in the granddaddy of all roadraces.

That’s possible because FX rules try to balance performance across very different motorcycle engine designs. Fours are limited to 600cc, while liquid-cooled Twins are given 750cc, and air-cooled Twins (Buell and Moto Guzzi) can go all the way out to 1350cc and are allowed more extensive modifications. The formula is somewhat arbitrary, but has been tweaked to produce essentially equivalent engine performance.

According to company founder Erik Buell, his namesake’s involvement in the class isn’t just because he likes to go racing.

“We’re doing it because developing a bike for racing is the best way to achieve bulletproof reliability in production bikes,” he says. “Racing is the ultimate test.”

Buell goes on to explain that it’s hard to test real-world reliability to the “six sigma” level (six standard deviations, or 3.4 failures per million products) with even the accelerated and rigorous test schedule Buell currently uses, which throws in wheelies and full-throttle acceleration runs galore. “You run into that 0.01 percent rider-usually European-who just hammers the bike,” he explains. “The only duty cycle that exceeds what he does is racing.”

That was the logic that Buell took to Harley engineering. He requested Harley help develop race engines with the understanding that Buell would apply what it learned in racing to production. Buell also wanted to be able to supply dealersponsored teams with a baseline engine that made competitive power without hand-grenading itself-an all-too frequent occurrence with the early Sportster-based engines in Pro Thunder racing. Fortunately, much of what had been learned in the early days of Pro Thunder had been applied to the XB engine design-it was already a generation ahead of the old Buell powerplants. Now, the idea was to take it to the next stage.

Jon Bunne and Gary Stippich are the engineers responsible for the XB racing development program and building race engines, respectively. According to Stippich, who’s been developing engines for Buell as long as Buell has been associated with Harley, they’ve come a long way.

“When we started running Pro Thunder, we were happy with 115 horsepower,” he says. “Don Tilley and I were in competition, and we kept pushing the power up. It was exciting getting to 122 horsepower. Now, if an engine dynos in the high 120s or low 130s, we’re asking, ‘What’s wrong?”’ According to Buell, a good ’04 race motor put out about 135 horses.

The newfound power comes from increased displacement and from a lot of small lessons learned over the years. Instead of an XB12’s undersquare 3.5-inch bore and 3.812-inch stroke, standard engines were bored out to 3.812 inches with Nikasil-lined cylinders and de-stroked to 3.6 inches. This produced 1348cc with more rev potential than a stocker. The bottom end was reinforced with a lightened crankshaft and special 8620 alloysteel connecting rods. Silver-plated cages guide the big-end bearings, while Timken tapered-roller main bearings support the primary side of the crank.

The oil system relies upon a very special three-stage Pro-Flow pump mounted in place of the stock unit. It scavenges the cylinder heads directly through a separate stage and external lines. “Before, we were always worried about filling up the catch bottle,” says Stippich. “With the Pro-Flow pump, we don’t get oil out the breathers.”

Tilley, a tireless innovator always looking for the next demon tweak to get power out of his Pro Thunder bikes, first developed the current oil system. Stippich freely credits Tilley with a number of currently used parts, such as the lightweight forged pistons (with a 14.0:1 compression ratio) he designed along with Wiseco, and the NASCARstyle valve springs that are stable to 8500 rpm and beyond.

While the modified bottom end holds together at high power and revs, the power itself came from the latest cylinder heads and intake system. The heads start out as XB castings, but are machined differently on production equipment at Harley’s Capital Drive plant. The exhaust valve is rotated out slightly from its contact point with the rocker arm to allow more valve-to-valve clearance. That room allows fitting a big 1.9-inch titanium intake valve and a 1.6-inch titanium exhaust valve. The exhaust ports are essentially stock, just blended to fit the larger valves, while the intake ports are much modified, essentially carved by Stippich on the flow bench. The biggest single gain on this year’s engine came with the introduction of the dual-throat intake system. Fully 51mm in diameter, these massive twin throttle bodies flow enough air to give, according to Stippich, a 5 to 10 horsepower boost over the single throttle body previously used. A modified version of the standard XB engine computer controls the fuel-injectors.

The valvetrain is surprisingly close to stock. The hydraulic lifters, good for more than 7500 rpm on an XB9, are straight from production and unmodified, while stock pushrods give way to special metal-matrix composite struts that shave weight by 25 percent. Red Shift #643 grind cams provide more lift and duration, but the lightweight valves and advanced springs keep everything under control to beyond the rev limits of the 3.6-inch stroke.

The cases have been modified to take a transmission trap door, essential as ratios are sometimes juggled at trackside. Standard fitment is an Andrews Y-ratio gearset for second through fifth with a lower S-ratio first gear to provide a stronger launch. For most circuits, just four gears are used after the start; if all five are required because of a hairpin or tight turn, a taller first will be used to make the downshift from second smoother. The clutch remains stock-even the plates-except for the use of stiffer springs.

A few times last year, Buell ran a shortstroke version of this engine. With the same big bore and the stock XB9 stroke of 3.125 inches, it displaced only 1170cc, and revved higher than the 1350cc. It made slightly less power, but with a smoother, wider band. Future development may focus around this shorter stroke, but with a further bore increase to bring the displacement back to the class limit.

The chassis carrying this hot-rod Twin is very close to the production bike’s spec. The air-intake hole in the left frame spar is welded shut to increase fuel capacity by almost a quart, and ram-air hoses lead from the front of the fairing directly into the airbox instead of through the closed-off hole. Stock Showa forks were used for much of the season, but eventually an Öhlins fork offering slightly smoother action and less friction was fitted to Ciccotto’s bike. Barnes continued with the Showa. Both forks are carried by triple-clamps with 3mm less offset, giving a little more than a tenth of an inch more trail than stock. The rear shock was either a Penske or an Öhlins, depending on rider and team preference.

Buell engineers substituted chain drive for the stock belt, mostly to make gearing changes possible. This required a modified swingarm with a movable axle for chain adjustment. Emphasizing how well the stock bike uses its axle clamping to stiffen the swingarm assembly, the racing swingarm with its sliding axle was actually less stiff than that of a production XB-something that’s on the list of things to improve for next season. The racing arm is also about 1.5 inches longer than stock, giving a more front-heavy weight distribution that helps minimize wheelies with the substantially greater power and lighter weight of the racer (around 365 pounds,

15 over the class limit) compared to the streetbike.

The racing XBs ran stock front wheels, with a slightly wider 17 x 5.75-inch Marchesini on the back. The teams ran Buell’s Zero Torque Load “inside-out,” single front brake disc as well, though halfway through the season they began using a new, Buell-designed eight-piston caliper.

“The caliper is a good example of a possible production part we’re developing here,” says Bunne. In this case, the pad compound initially used with the caliper was wrong, and caused some problems for Barnes. By the end of the season, however, the caliper was fitted routinely with no problems and gave noticeably lighter feel and more power.

There were other learning processes during the year. The dealer teams began the season running the bikes considerably higher on their suspensions than a standard XB, which increased the antisquat geometry at the rear excessively. After conferring with the engineers who designed the XB, the teams returned the suspension height to close to stock. Handling proved a real strength for the Buells, with radar guns consistently showing higher cornering speeds than the 600s. Even top speed was proving competitive. “We’ve always been afraid of bigstraightaway tracks,” says Terry Gallagher of the Hal’s team. “But at Brainerd, the fast Hondas were being clocked at 173 to 175 mph, and we were pulling 171. It was pretty close.” Buell believes the bikes are still slightly behind in power-to-weight ratio, but have better aerodynamics. In the races, the XBs carried more speed through the corners, got on the gas sooner and accelerated harder initially, then had the 600s gain ground back through the next few gears.

Indeed, throughout the entire season the Buells were consistently top-10 run-

ners. Part of the success was a newfound consistency. “Erik is adamant about not testing at racing events,” says Bunne. “If we haven’t run a configuration through a race-length test session, it doesn’t race.” While the XBs didn’t get a whiff of Miguel Duhamel and his blazingly fast, very exotic, 17,000-rpm factory Honda CBR600RR, they were running ahead of a lot of other 600s.

The bikes will be quicker yet next season. Engine development proceeded over the winter in anticipation of Daytona, with the intent of eventually offering a production racing engine in a box available to any privateer team that wants one. Buell has made racing a central part of his future plans for the company. “This is not racing to sell racereplica lookalikes,” he says. “If you have to look a rider in the eye after a failure, a theoretical problem becomes very real.”

Buell goes on to discuss the new brake caliper. He points out it was designed from first principles, with its clamshell shape chosen for the highest possible stiffness-to-weight ratio, and thoroughly optimized with finite-element analysis. He talks about a new racing exhaust system designed by Harley’s analytical sound group, which cuts noise by more than 15 decibels while actually improving power. “We have to invent stuff,” he says. “There’s a lot of copying going on in racing. But not with us. No one is doing some of the things we’re trying to do. It’s fun.”

It will be even more fun, if more nervewracking, for Buell to watch his namesake bikes contest the Daytona 200.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAussie Rules

March 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOn the Trail of the Mighty One

March 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTelephone Teams

March 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2005 -

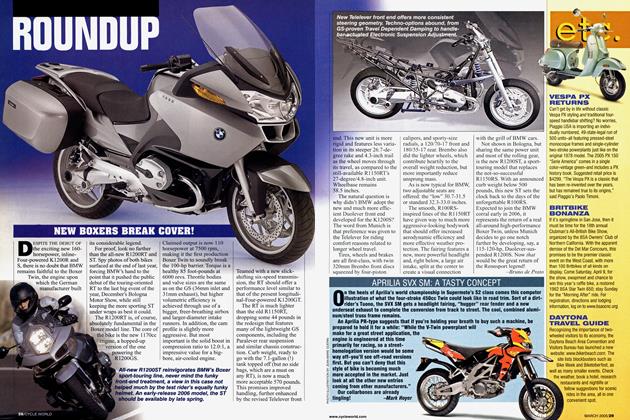

Roundup

RoundupNew Boxers Break Cover!

March 2005 By Bruno De Prato -

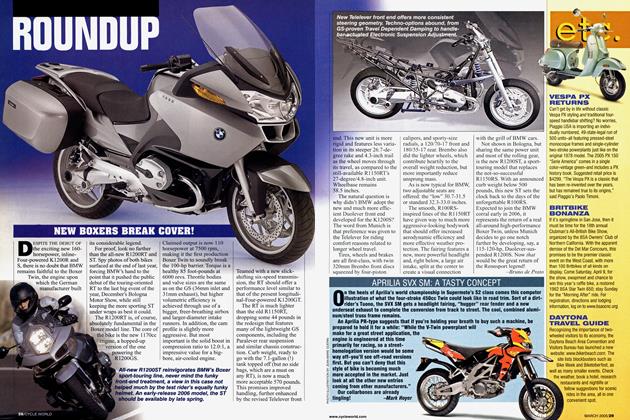

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Svx Sm: A Tasty Concept

March 2005 By Mark Hoyer