SERVICE

Paul Dean

Stalking on a VFR

My problems are two-fold. First, Nicole Kidman continues not to respond to my queries regarding her availability. Second, I’m experiencing electrical difficulties with my 1994 Honda VFR750 and am hoping Cycle World can offer some advice.

On my way to work the other day, the speedometer fluctuated wildly and the dash lights (turnsignal indicators, high beam and neutral indicators) were dimmer than usual. When I tried to leave work that same day, the bike would not crank over and made all the sounds typically caused by a weak battery. I recharged the battery for about half an hour and almost made it home but had to push the bike the final mile or so.

I had these same problems last summer and the dealer told me I needed a new battery, so the one in there now is only a year old. Is it possible that it, too, could now need to be replaced? I find it hard to believe that a motorcycle battery is only good for about a year, given proper maintenance (winter recharging, etc.). I’m also wondering if other factors could be involved. I’ve noticed when riding at night that the intensity of the headlights will fluctuate from normal brightness to a noticeably more intense brilliance (as if I had turned on my high beams) and then back again.

James Eng Trenton, New Jersey

Something indeed has gone awry with your wiring. And your VFR obviously has an electrical problem, too. I know nothing about your malfunction, but as far as the bike is concerned, it’s very likely that the voltage regulator/rectifier unit has failed.

Though the 1990-97 VFRs are fantastic motorcycles, they also are notorious for persistent regulator/rectifier failures. I experienced a similar problem with my own ’90 VFR in 1997 but only had to replace the regulator; the battery survived for another few years.

There are several symptoms that can arise from this failure, depending upon which segment of the regulator/rectifier has gone belly-up. These can include insufficient charging current, no charging current whatsoever, and the infusion of large amounts of AC current into the DC electrical system that, at its worst, can blow fuses, burn out light bulbs and kill the battery.

Because your current battery lasted a year, both the previous failure and this latest one may not be the result of a reg ulator problem; vibration and excessive shaking can kill a battery long before its time. So before you do anything else, make sure that the battery is firmly secured by its tie-down strap and that all of the rubber cushioning pads in the battery box are in place. Also, disconnect the battery from the electrical system-or remove it altogether-then check its electrolyte level and charge it with a 1-amp charger or a Battery Tender. If it holds the charge, that will be a good indication that the regulator/ rectifier is at fault.

I suggest you buy or borrow a service manual for your VFR and follow the diagnostic procedure for troubleshooting the charging system. I could explain a lot of it, but there ’s not room here for the detail information, photos and diagrams that can prove very helpful in tracking down these kinds of problems. If you don’t have the tools or temperament for such work, take the bike to your dealer and explain the situation very thoroughly. If he owns a working forebrain and has been in the Honda business for more than an afternoon, he’s surely aware of the VFR regulator/rectifier problems.

My advice regarding Nicole is simple: If you ’re going to keep sending her letters, text messages and e-mails, use your real name and stop signing them “Tom.”

Cool under pressure

Is a bike’s oil pressure affected, as in lowered, if you add an oil cooler? Also, does the size of the cooler have any effect on pressure?

Curtis Helton White Pine, Tennessee

Not at all. Theoretically, you could install an oil cooler that s as big as your garage door and it would not reduce the oil pressure one bit. You would have to greatly increase the amount of oil in the system, of course, to compensate for the huge volume of the cooler, but the pressure would remain the same.

This principle is not unlike that of a braking system, in which any applied pressure is consistent throughout. If squeezing the lever or pushing the pedal creates 50 psi at the master-cylinder piston, there also is 50 psi in the narrow little brake lines, 50 psi in all of the large-diameter caliper bores and 50 psi everywhere in between. The speed at which the brake fluid moves through the various parts of the system will vary according to each component’s volume, but the pressure, in pounds per square inch, remains constant. The situation is no different in an engine ’s lubrication system, which doesn’t care if the pressure is being created by an oil pump or someone squeezing a lever.

It’s not trail "breaking"

Could you provide an explanation of “trail-braking,” specifically as a technique when cornering a motorcycle? This term regularly appears in Cycle World articles, yet I have never seen it defined.

Steve Tennyson Posted on America Online

Trail-braking is the technique of using the front brake while the bike is being leaned into a corner. It’s a tactic used primarily by roadracers and experienced sportbike riders on backroads.

In days gone by, virtually all braking on corner entry was performed while the bike was still vertical, whether in roadracing or during fast street riding. The rider would apply maximum front brake while approaching the corner, then release the lever altogether just as he banked over into the turn. Back in that era, significant use of the front brake while cornering would cause tires to distort, forks to twist, frames to flex and, quite often, riders to fall.

Since then, technology gleaned mostly from racing has allowed tires to have amazing levels of road adhesion and far less tendency to distort under load, forks to have exceptional torsional rigidity and frames to flex only when, where and to the extent desired. And as these technologies progressed, riders and racers gradually found that they often could continue braking after initiating a turn.

The amount of braking force has to be progressively reduced as the lean angle increases and the bike gets get deeper into the turn, but once the technique is learned and judiciously applied, it can allow quicker lap times and faster corner entries.

The caveat, though, is that if just a wee bit too much brake is applied as the bike is being banked over, a low-side get-off is the usual outcome.

Dyna dynamics

I enjoyed the “True-Track Swingarm Pivot Anchor” product evaluation in the October, 2005, issue. It was very informative. My only question is, does the swingarm pivot problem that affects Harley’s FL models apply to the Dyna series? The Dynas also are rubber-mounted, so it stands to reason (in my way of thinking, that is) that the problem would be present on that model, as well. I’ve been debating whether or not to buy a new Dyna, so your response will be very helpful. Ricky Hayman Austin, Texas

Although the Dynas do use a rubber-mounted drivetrain, their mounting system is quite different than that of the FL touring models.

On the FLs, the front of the entire driveline assembly (engine, transmission, swingarm, rear wheel) sits on a big rubber donut at the front of the engine, and the rear is supported only by two large rubber bushings, one at each swingarm pivot. So, the driveline is > largely free to float around somewhat in all planes, and the two stock stabilizer links (one in front of the engine, one above the cylinders) are too far from the rear wheel to prevent the whole works from being shifted side-to-side during hard cornering. The True-Track is a third stabilizer that mounts just ahead of the swingarm to minimize that side-to-side movement.

Recall Roster

NHTSA Recall No. 05V372000 Suzuki Burgman 650, Burgman 400 Model years: 200304 Number of units involved: 5869 Problem: On certain scooters, if the ignition switch is not fully turned from the “Off” to the “On” position, there may be unstable contact between the ignition switch contacts. This can cause arcing in the ignition switch that could melt the switch’s internal base plate. If the scooter is ridden in this condition, the ignition switch may fail, causing the engine to stall and the lights to go out, and the operator may be unable to restart the engine. This could possibly result in a crash.

Remedy: Suzuki dealers will replace the switch terminal case assembly. Owners who do not receive this free remedy should contact Suzuki at 800/255-2550.

On a Dyna, however, the engine mounts are designed to allow only the up-anddown and front-to-rear movement of the entire driveline necessary to absorb engine vibration. The mounts are rectangular rubber biscuits sandwiched between vertical steel sideplates that bolt to the frame, with one mount at the front of the engine and one at the rear, aided by a single stabilizer link above the cylinders. The sideplates prevent the side-to-side movement that occurs on an FL, making an additional stabilizer link unnecessary. What’s more, because a Dyna is a much lighter machine than a big FL tourer, the side loads applied to the rear wheel during most cornering situations are considerably less, further reducing the need for additional stabilization.

Springy thingies

When cruising the local bike hangouts, I’ve heard some riders talking about different kinds of fork springs, using terms like “progressive” and “dual-rate.” Could you please explain what these terms mean? I’d ask them, but I don’t like getting ridiculed for being uninformed-even though when it comes to some technical subjects, I am pretty clueless. Dennis Ensberg Schoharie, New York

There are three basic types of coil springs used on forks and shocks, as well as on countless other devices: straight-rate, progressive-rate and dual-rate. Springs are usually rated by the amount of force required to compress them one inch.

Straight-rate (also called constant-rate) springs are wound so that all the coils are evenly spaced and of the same diameter, so the same amount of force is required for each inch of compression. Take, for example, a 25-pound straight-rate spring: Compressing it one inch requires 25 pounds of force, and the next inch requires another 25 pounds, and so on. This continues until the device either reaches the end of its travel or the spring “coil binds.” That’s what happens when all of the coils have been fully compressed against one another, an event that takes place all at once, since the spacing between the coils is equal.

On a progressive-rate spring, the coils are spaced so that each wind is slightly closer to the next one than the one before it, with the last two almost-but not quite-touching one another. As the spring is compressed, the first of those closely spaced coils binds, then the next, then the one beyond that, continuing along the length of the spring until all the coils are bound—if, of course, the device doesn’t run out of travelfirst. Each time one set of coils binds, the effective length of the spring is shortened, thereby increasing its rate. So, the farther the spring compresses, the more force is required to compress it each additional inch. A progressive spring with, say, a 10to 22-pound rate working within five inches of travel would require 10 pounds to compress the first inch, then 13 additional pounds for the second inch, 16 more for the third, another 19 for the fourth and 22 more for the fifth.

Then there are dual-rate springs, which are wound with two different springpitches-one with coils spaced evenly but reasonably far apart, another with coils also spaced evenly but closer together As the spring compresses, the initial rate is determined by the total length of the entire coil, regardless of how closely or widely the coils are wound. But when all of the closely wound coils bind, which usually occurs in the earlier stages of compression, only the widely spaced ones are left to continue compressing. If you had a 10/2O-pound dual-rate spring, it initially would require 10 pounds offorce for each inch of compression until the closely wound coils became bound, at which point the rate would go directly to 20 pounds per inch.

Potentially, dualand progressive-rate springs offer an advantage in their ability to be more compliant at the very beginning of the suspension stroke yet still stiff enough to soak up big bumps and prevent bottoming. Based on specific needs and applications, however, not all motorcycles are equipped with them.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Letters to the Editor” button and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMiscellany

December 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKing of the World

December 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFire, Misfire

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2005 -

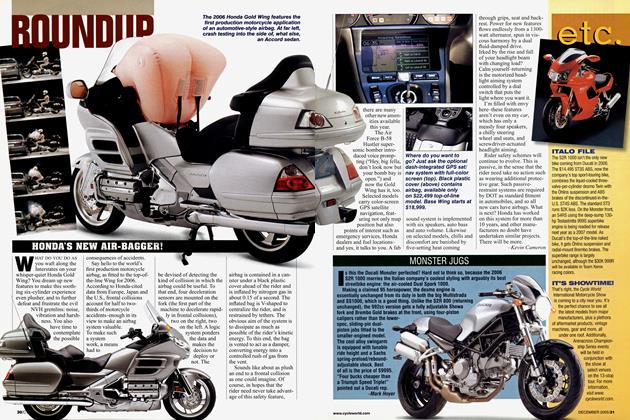

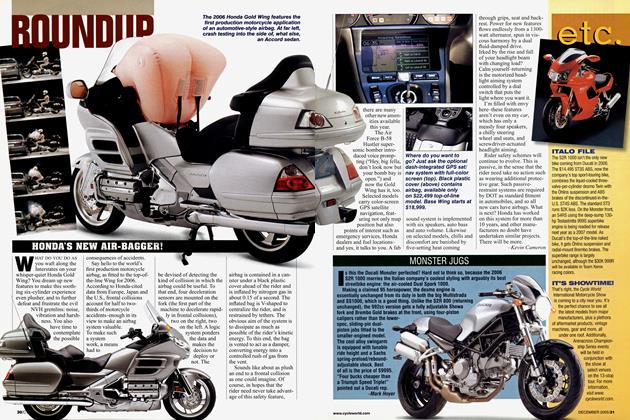

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New Air-Bagger!

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Jugs

December 2005 By Mark Hoyer