Clipboard

RACE WATCH

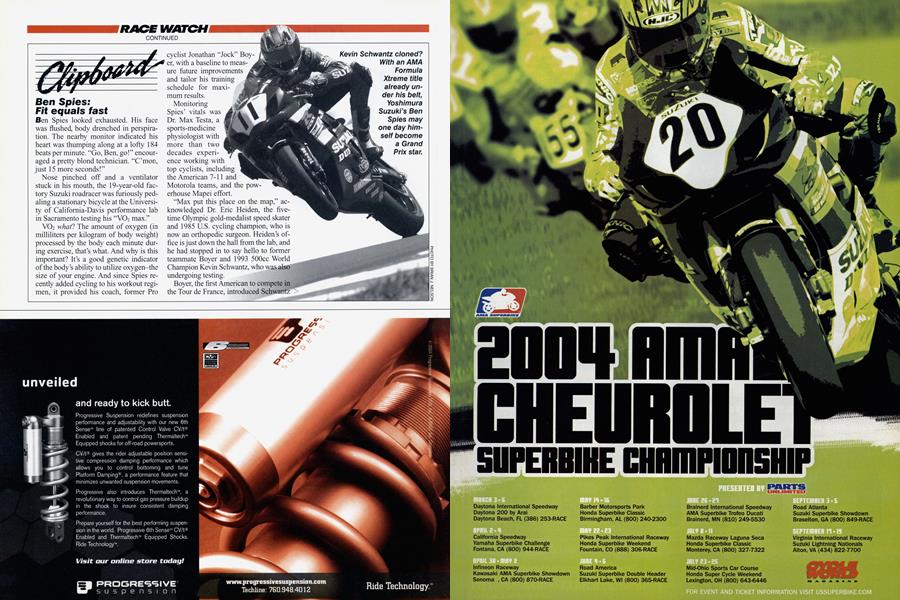

Ben Spies: Fit equals fast

Ben Spies looked exhausted. His face was flushed, body drenched in perspiration. The nearby monitor indicated his heart was thumping along at a lofty 184 beats per minute. “Go, Ben, go!” encouraged a pretty blond technician. “C’mon, just 15 more seconds!”

Nose pinched off and a ventilator stuck in his mouth, the 19-year-old factory Suzuki roadracer was furiously pedaling a stationary bicycle at the University of California-Davis performance lab in Sacramento testing his “V02 max.” V02 what? The amount of oxygen (in milliliters per kilogram of body weight) processed by the body each minute during exercise, that’s what. And why is this important? It’s a good genetic indicator of the body’s ability to utilize oxygen-the size of your engine. And since Spies recently added cycling to his workout regimen, it provided his coach, former Pro cyclist Jonathan “Jock” Boyer, with a baseline to meas ure future improvements and tailor his training schedule for maximum results.

Monitoring Spies’ vitals was Dr. Max Testa, a sports-medicine physiologist with more than two decades experience working with top cyclists, including the American 7-11 and Motorola teams, and the powerhouse Mapei effort.

“Max put this place on the map,” acknowledged Dr. Eric Heiden, the fivetime Olympic gold-medalist speed skater and 1985 U.S. cycling champion, who is now an orthopedic surgeon. Heiden’s office is just down the hall from the lab, and he had stopped in to say hello to former teammate Boyer and 1993 500cc World Champion Kevin Schwantz, who undergoing testing.

Boyer, the first American to compete the Tour de France, introduced Schwantz to cycling 15 years ago. “Up until then, mostly what I did was dabble on my motocross bike in the winter,” Schwantz admitted. “Having dislocated my hip and banged up my feet, I didn’t enjoy running or any other type of aerobic fitness.”

Unlike golf, which was “just something to chew up part of the day,” cycling offered Schwantz a whole new perspective on his racing. “I started out just riding on the various tracks around Europe,” he said. “I was able to see bumps and cracks in the surface that I otherwise never would have seen on my Grand Prix bike, even going slow while breaking-in an engine. Plus, it was a great workout.”

Now, Schwantz is returning the favor. “Roadracing doesn’t require a lot of cardiovascular, but you need to be able to maintain your focus,” explained Boyer. “The more fit you are, the better you can maintain your focus.” Boyer’s knowledge comes first-hand: After retiring from the Pro peloton, he tried his hand at roadracing. He even won an endurance event at Sears Point. He still has his racebike, a kitted Yamaha OW-01.

Spies had expressed an interest in cycling last year, having seen Schwantz and Yoshimura Suzuki teammate (and Treksponsored) Mat Mladin doing “an insane amount of riding.” But a horrific, highspeed crash while testing tires at Daytona last October grounded him for four months while he recovered from extensive friction burns.

“I’d like to think I was somewhat instrumental with Ben’s getting into cycling,” said Schwantz. “But meeting Jonathan and riding with him, that was really big, too.”

Spies greatly respects the 48-year-old Boyer, but is quick to poke fun. “I call Jonathan ‘O.T.’-for Old Timer,”

he laughed. “He won the Race Across America in 1985, riding 3180 miles in nine days! I think that’s completely nuts.”

Boyer describes Spies as a typical teenager “full of questions.” Schwantz agrees. “Motorcyclewise, he doesn’t ask me that many questions,” he said. “Bicycle-wise, though, he’s over-the-top enthusiastic.”

Already, Spies has seen dividends from cycling. “At Fontana, I’d only done two solid weeks of cycling, but I could definitely tell a difference,” he said. “I battled pretty hard and won the Superstock race. Then, in Supersport, I finally got past Jamie Hacking with three laps to go, and started running down Tommy Hayden. I did my fastest lap of the race-just three-tenths off my polewinning time-on the last lap. And I was just getting started; I could have done 10 more laps. It’s not just that I can feel myself getting into better shape. I feel a whole lot calmer. I’m not so jittery.”

Testa isn’t surprised by Spies’ findings. “The main benefit of riding a bicycle is that it improves your general level of fitness, your cardiovascular condition,” he explained. “This is important for Ben, because he has a very stressful job. Those races can last a long time. There is also a psychological benefit that comes with the release of endorphins-a ‘wellness’ hormone that your body produces when you do prolonged, aerobic activity.

“He will be able to sustain the physical act for longer with less decay in performance,” Testa continued. “There is a correlation between the level of lactic acid buildup and precision of movement-the more lactic buildup, the less precise and the greater risk of injury. If his body is able to clear lactic acid from the muscle more quickly, his brain will be clearer, and he’ll have better reaction times.”

Spies performed well at the test, but didn’t meet his goal, which, of course, was to beat Schwantz. “My VO2 max was a little better than his,” Schwantz admitted. “But like I told him, I’ve been riding for years. It’s like anything: You need time in the saddle. Fitness doesn’t just happen.”

Testa was nevertheless impressed by Spies’ effort. “After only a couple months of riding, that’s pretty amazing,” he said.

“I’ve never done anything that got me so much information in so little time,” Spies said. “Now, I know where to keep my heart rate, and how to train to get the best out of my body. It will be cool to come back next year with a full year of riding under my belt and see how much I’ve improved.” -Matthew Miles

Antonio Cobas, 1952-2004

Antonio Cobas, chassis pioneer, journalist and long-serving Grand Prix team engineer, has died from cancer aged 52. The irascible and difficult Rex McCandless designed the Norton Featherbed twin-loop frame that defined motorcycle chassis from 1950-1980. The next chassis revolution, beginning in 1978, bears a different name-that of Cobas. In 1978, Cobas developed the first of his strictly triangulated multitube “Siroko” chassis, of which 54 were built, for use with Yamaha or later Rotax engines. In 1981, Sito Pons would race a Siroko-Rotax in 250cc GP, beginning a long-lasting relationship with Cobas. Then in 1982, Cobas switched to a new concept in building the twin-aluminum-

beam JJ Kobas-Rotax bike, on which Carlos Cardus was European Champion in 1983 (in status, the Euro Championship was the rough equivalent of today’s World Supersport).

A strong case can be made that Cobas created both the major themes of modern motorcycle chassis design-the multitube “trellis” used by Ducati and the aluminum beam favored by Japanese companies. His work came at a time when high-powered 500 and 750cc racebike chassis were fresh out of ideas, playing out the last notes of the McCandless era. Cobas showed two paths to the future.

Does anyone ever really “invent” anything? No one works in a vacuum. Ducati’s Dr. Taglioni drew that company’s first trellis design in 1981, and surely both he and Cobas knew of Maserati’s Tipo 61 “birdcage” race-car chassis of 20 years before. Textbooks of bridge design are just quantified common sense. But Cobas lived in the creative tension of knowing current practice was failing, and of yearning for a fresh synthesis. Yes, he surely knew of the full monocoque chassis of the OSSA 250 of 1969, the experiments of Eric Offenstadt and the very similar Kawasaki KR500 chassis. But the twin-beam chassis he designed supplied increased stiffness without obstructing serviceability. It is even possible that the twin-beam idea arose in part from the need to make room for the rear-facing exhaust port of the Rotax engine. That point may have especially recommended the design to Yamaha, whose new squareand V-Four 500s had such ports.

Just as McCandless combined already-existing elements (swingarm, telescopic fork, twin-loop chassis) into a superior, working whole, so Cobas acted as a lens, gathering the “light” of many existing design elements, then using his understanding to focus them into new, coherent images. His Siroko design made sense because it used almost no material in bending-only in tension or compression. This allowed it to be both lighter and stiffer than twin-loop chassis. Then, making the same leap aircraft structure had made 40 years before, Cobas replaced many steel tubes with large, thin sheet-metal boxes. This, by giving the small amount of metal used greater “leverage” over the stress it had to carry, allowed chassis weight to be cut in half again, with again an increase in stiffness.

Cobas also saw what most others had not-that because of increases in tire grip and engine power, engine and rider weight had to move forward significantly. Major teams were slow in adopting this, but physics would force them to it. Cobas’s work foretold the future.

In 1988, Pons went to the Campsa Honda team and made Cobas his tech chief. Upon Pons’ retirement and creation of the Honda Pons team, Cobas continued in that role until his death this past April. When he became too sick to travel to races, he continued to advise the team via telephone and e-mail. His influence upon motorcycling and the example of his understanding will long continue. -Kevin Cameron

Living legends head Down Under

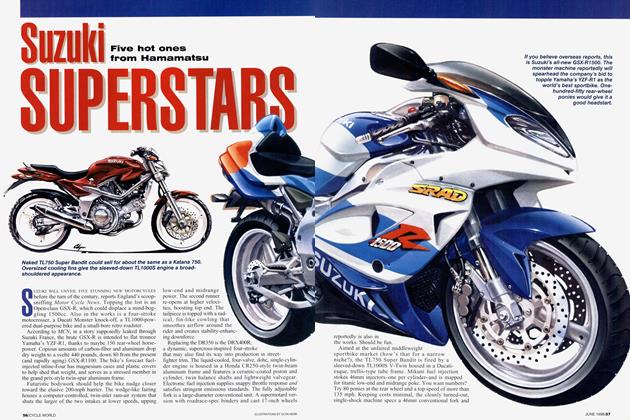

Australian vintage-dirtbike magazine VMX played host to two living legends of motocross at the third-annual Suzuki Classic Dirt weekend held this past March at Barrabool, one hour south of Melbourne.

For 1982 500cc World Champion Brad Lackey, this was his first trip back to Australia following a brief and almost forgotten appearance at a stadium motocross on the outskirts of western Sydney in the early 1980s.

For Jim Pomeroy-the first American to win an MX Grand Prix in Spain in 1973—it was his first-ever visit Down Under. The modest Bultaco rider from Yakima, Washington, reaffirmed this when he quipped, “I had no idea I had so many fans down here.”

Pomeroy also had no idea that his Australian fan base would be increased tenfold by the time he left Australia two weeks later, either. After Classic Dirt Three, Australia’s “Bultaco Mafia” took over as his chaperones for an East Coast field trip that included trail riding, motocross schools, nostalgia dinners and “hops research” field trips.

Suzuki Classic Dirt enjoys a reputation as a kicked-back, low-stress weekend, the pace of which was perfect for the two American stars, who fell in love with the rolling Barrabool circuit immediately. Australia’s ongoing drought had bleached the usually green grassy hills to a parched brown, leaving Northern Californian Lackey to comment, “Wow, this looks just like home!”

The track’s reputation as one of Australia’s best natural-terrain racing venues was backed up by Pomeroy, who commented, “This place is world-class, simply one of the best Eve seen anywhere.” If world-class was the theme for “CD3,” that was reinforced for two whole days with Pomeroy and Lackey taking on their roles as international classic motocross ambassadors with energy and passion. Their candid, easygoing nature was right at home with the hundreds of Aussie vintage fans who dropped by to say “G’day,” grab an autograph and shoot the breeze. Somehow, the old-dirtbike culture has a lingua franca of its own-one that cuts through accents, removes cultural barriers and builds a common bond that is universal.

Bultaco legend Pomeroy was kept well stocked with immaculate classic Pursangs, and left no doubts that a twinshocker is a match for any later-model “Evolution” bike. He even tackled Lackey’s newer Suzuki RN82 GP lookalike head-to-head on a few occasions.

Pomeroy’s speed and fluid riding style left the Aussie fans stunned. “I’ve never seen a guy who was so at one with a bike,” said one longtime vintage racer.

Equally as fast on the track and congenial in the pits was Lackey, whose deep knowledge of motocross history made a lasting impression on the young dirtbike magazine scribes who made the trip to grab an interview. They probably learned more during their interviews with the champ than at any other time during their careers!

For the hordes of low-key classic riders who are not regular racers, Classic Dirt provides a unique opportunity to dust off their much-loved old dirtbikes and blow out the cobwebs. This year, attendance was mandatory if you wanted the one-off opportunity to grab some track time alongside two of the sport’s living legends. -Ray Ryan

Remembering the late, great John Britten

Five-time New Zealand Superbike Champion Andrew Stroud etched his name in the record books by winning the inaugural John Britten Memorial Superbike race at Christchurch’s Ruapuna International Raceway this past March. It was a fitting tribute by the man who rode a Britten to victory in the 1996 AHRM A Battle of the Twins race at Daytona, as he chose to bide his time behind Auckland’s Ray Clee in both races before scorching through on the last lap to win.

Brainchild of Christchurch enthusiast Peter Fenton, the Britten Memorial was held to honor the late artist, engineer, inventor and innovator who designed the world-beating VI000 racers. The event boasts the richest prize fund in New Zealand motorcycle racing, Stroud claiming an impressive $15,000 and the magnificent Britten Memorial trophy for his efforts. On this occasion, the leading riders were all aboard Suzuki GSXR 1000s, with Wanganui’s Brian Bernard stepping up to take third place behind Stroud and Clee in both races.

Fenton pronounced himself pleased with the 4000-strong spectator turnout, the biggest crowd to come to Ruapuna for a motorcycle race in many years. Next year’s second-annual event, scheduled for March 19-20, will commemorate the 10th anniversary of Britten’s passing, and to that end Fenton is attempting to get as many VI 000s as possible to return to New Zealand.

“The most bikes they have ever had in one place at one time is four,” he says. “I have five lined up so far and will be trying real hard to get as many of the others as possible. To get all 10 would be amazing!” -John Hawkins

View Full Issue

View Full Issue