In Pursuit of Greatness

RACE WATCH

Kurtis Roberts takes aim at MotoGP

MATTHEW MILES

KURTIS ROBERTS SHOULD HAVE been a trial lawyer. At least that's what the straight-talking 25-year-old has often been told by friends and former teachers. Ever since he can remember, however, the youngest son of three-time 500cc World Champion Kenny Roberts has wanted nothing more than to race motorcycles, and to be a world champion himself.

This year, Roberts will get his shot at MotoGP greatness aboard his father’s home-built, the continually evolving Proton V-Five. Roberts Sr. was happy with his 2003 first-stringers-Jeremy McWilliams and Nobuatsu Aoki-but they were getting on in years. Going to an up-and-comer made sense for the future. “If we let younger people go by us, it’s much more difficult to grab ’em later,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to get into a bidding war with Honda over Nicky Hayden, for example.”

Kurtis already has international knowhow, having contested the 250cc World Championship in 1997, albeit with horrible results. “Going into that season, I had only ever done 12 or 13 races, so I had no experience whatsoever,” he laments. “We started off with Aprilias, but the team couldn’t get them to run. In France, for example, where I broke my leg when the thing seized, we’d only done eight laps the whole weekend. The only Grand Prix it really ran, I fell off while I was in eighth place.” Switching to Hondas-a three-year-old kitted RS250 and a year-old stocker-failed to net better results. “The Aprilias didn’t run that much, but when they did at least they were fast,” he says.

Discouraged, Roberts returned to the U.S. He spent the next six seasons racing stateside in the AMA series, earning one 600cc Supersport and two Formula Xtreme titles for Honda. In 2001, he moved up to Superbike, scoring podium finishes at Daytona, Brainerd and Virginia. Injury ruined Roberts’ ’02 campaign, but he came back strong this past season, winning two races and placing third in points behind Yoshimura Suzuki riders Mat Mladin and Aaron Yates and their rampaging GSX-R 1000s,

Despite this success, Roberts viewed his American racing as a means to an end. “Winning the AMA Superbike Championship was never a goal of mine growing up,” he says. “It was never something I had to do. My dream was always to go back to Europe and win the world title.”

That explains why Roberts turned down lucrative offers to remain in the U.S. for 2004. “I could have raced Superbike, Formula Xtreme, Superstock, anything I wanted in America with Honda,” he says. “Or with other companies. Ducati was talking to me about riding its Superbike. I told Honda I would stay one more year in America if I were guaranteed a two-year deal in Europe after that-or they at least make an effort to get me over there.”

Honda wouldn’t make that commitment. But with McWilliams headed to Aprilia, the door at Proton was wideopen. “My dad had expressed interest in me getting on the Proton for a couple of years,” Roberts explains. “I’d been looking to do that, mainly to give something back to him. I’m not doing it for the money. I’m doing it because I want to, and because I believe in the program. Of course, you always want to be on the best bike. But in my heart, I wanted to do this deal because it is a family thing.”

Roberts tested the V-Five at Spain’s Circuito de la Comunitat Valenciana in early November of last year, just days after McWilliams and Aoki finished 12th and 17th, respectively, in the series’ final round at the same track. His best lap, a 1:34.7, bettered the Ulsterman’s qualifying time by .2 second, and would have put him on the fourth row of the > grid, a full row ahead of brother Kenny Jr., the 2000 500cc world champ, on the star-crossed Suzuki GSV-R.

“It’s an easy bike for me to ride,” Kurtis enthuses. “It’s very neutral. With the Honda RC51, I had problems turning. The Proton doesn’t have that problem. At the test in Valencia, our problems had to do with the Dunlop tires. There was a lack of grip entering the comer that we couldn’t get out of the bike-and it wasn’t the bike.

“But as far as the first test went, I’m very happy,” he continues. “If we had

more grip, we could have gone even faster and every lap would have been very consistent. Right now, we don’t have that.” Roberts tested on Dunlops because Team KR’s former tire supplier, Bridgestone, pulled its support in favor of teaming with Kawasaki and Suzuki, both of whom use the Japanese tiremaker’s products as original-equipment on its production dirt and street models. “I would imagine it was a smart business decision,” Roberts Sr. says wryly. “But it kind of leaves us out in the cold. Unfortunately, putting these things together isn’t just one phone call.” At presstime, tire plans were still up in the air.

Kenny Jr., for one, isn’t the least bit surprised Kurtis adapted so quickly to the Proton. “When I moved up to 500s, my dad told me to get used to the weight, to get used to the horsepower, to get used to stopping the thing,” he says. “Kurtis found the MotoGP bike easier to ride than his Superbike. It’s not like jumping from a 250 to something that won’t turn, like a 500, and that accelerates much harder. He had been on something that was very similar to a MotoGP bike.”

Junior is also quick to point out that while Superbike is a natural steppingstone to the MotoGP four-strokes, only a top rider can make that transition with relative ease. “Kurtis isn’t just somebody who has ridden a Superbike,” he says. “He’s won Superbike races.”

Kurtis has worked hard to make himself a better rider, and credits three-time world champ Freddie Spencer, the smooth-riding Louisiana native who nipped Roberts Sr. for the 1983 500cc title, with helping him overcome personal hurdles.

“Freddie helped me understand what my dad had tried to show me,” Roberts says. “My dad and I are a lot alike. We don’t use a lot of words, and I was missing that last 2 percent of anything he said, which was preventing me from riding at 110 percent-safely. Freddie said, ‘Hey, why don’t you try this, and it will clear up all this.’ I did, and it made me understand everything my dad was saying, and why a bike does what it does.

“You could see it on TV last year. I looked a lot different-less aggressive-on the motorcycle than I had in the past,” he continues. “I didn’t back the thing in or use the rear brake that much. To me, it looked more effortless.”

While Roberts’ skill and determination aren’t in question, other factors that are out of his control-tires, for instance-can easily affect the outcome of a race, or even a career. No one is more acutely aware of this than Kenny Jr. “Kurtis has the talent,” he says. “We know he’s as quick as Nicky Hayden. Whether he’ll have the opportunity to show that, however, is a matter of being in the right place at the right time. And having the right amount of luck, which in racing is a huge part.

“When we won our world championship, we did it by using everything we had, but also by using the weaknesses of others,” he adds. “There are no weaknesses now. To get into the top 10, you have to have something that can get you into the top 10. Otherwise, you need some luck, some crashes, people taking each other out, or rain.”

Junior has enjoyed little success since winning the title three years ago. He’s struggled with different brands of tires, uncompetitive machinery and the departure of Warren Willing, the team’s technical director and a close personal friend. Last season, Junior’s worst on record, he finished 19th in points, two spots behind his teenage teammate John Hopkins. Often criticized for a lack of motivation, the quiet 30-year-old has said time and again that he will ride the hamstrung GSV-R to 100 percent of its capability, and not beyond. After all, he reasons, you can’t win races-or championships-if you’re sidelined with injuries.

Kurtis is just the opposite. “I want to push whatever I’m on to whatever extent, even if I can’t win,” he says. “I have this thing in my brain that’s always telling me someone could be doing it better. I want to make the bike go as fast as it can go. We don’t all get a chance to win, but I can sure as hell make the thing go from eighth to sixth. At the end of the day, if I made the bike do things it didn’t want to do and I went faster than I was expecting or faster than everyone else was expecting, then I’m happy.”

Kurtis and Junior have never raced against each other, partly due to the difference in their ages. (Kurtis did have a one-off ride on the two-stroke KR3 in Malaysia two years ago, but crashed on the opening lap of the race.) Growing up, both boys were good athletes, which led to a severe case of sibling rivalry. “When we were younger, we didn’t get along very good,” Kurtis admits. “Typical brother stuff, plus we have one of the most competitive families I’ve ever seen. Now, however, there’s no tension whatsoever about anything.”

In fact, Kurtis has nothing but respect for his older brother. “I feel the best rider in GPs is Little Kenny,” he says. “I’d rather watch Kenny ride a motorcycle on any day of the week than anyone else in the world. When I was little, I loved watching my dad. To me, there is no one as smooth as Little Kenny, even when he’s the fastest guy on the racetrack by 2 seconds. He always looks so effortless and fluid. I feel bad for him because he’s never been given the credit due him.” Kurtis is intelligent, and an engaging conversationalist. He was a good student, but never won the hearts of his teachers. “I was racing in Spain a lot, maybe three weeks at a time-half the school year,” he says. “I enjoyed some of the subjects, such as History. But I hated homework. One quarter, I didn’t turn in a single assignment. Going into the final, I had a 7 percent. But I got a 98 on the final. That upset my teachers, but at the same time, it got me out of a lot of stuff because they knew that I understood the information.” Roberts never pursued a college degree, but he may one day return to academia. Partly at the prodding of others, he has even expressed interest in law school. “It probably comes from arguing with a teacher about something, trying to get a grade I probably shouldn’t have gotten,” he says, only half-joking. “But I can always go to college. There’s no age limit on that. Right now, I need to do this.”

Taking the fledgling Proton to new heights will be no small task. Not just for Roberts as a rider, but for the 50-odd employees of his father’s U.K.-based GP Motorsports. With six Hondas and four Ducatis in the field, just cracking the top 10 will be a victory.

“My dad’s team could make a bike that’s better than a Honda,” Roberts says emphatically. “But they’re so small compared to Honda, and they have to develop and race at the same time. Honda doesn’t have to do that.”

No one knows that better than Roberts Sr. “From where we started, with the budget we had, to make something from nothing in a year-the first time the bike ever saw a racetrack was in practice for the French Grand Prix-we’ve come a long way.

“We don’t have 10 engineers on every aspect of the motor,” he adds. “Six or seven people put this thing together, had it manufactured and brought it to a racetrack. The bike will probably be 90 percent different this year. We’re keeping the vee angle, but the rest of it will be different.”

Despite the disparity in horsepower and top speed with the Hondas and Ducatis and Yamahas, despite constantly leap-frogging technology, despite unknowns with tires, Kurtis remains encouraged. “I want to do the best I can,” he says simply.

Can’t argue with that. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontArt of the Chopper

April 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Age of Tough Engines

April 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCutting It Close

April 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2004 -

Roundup

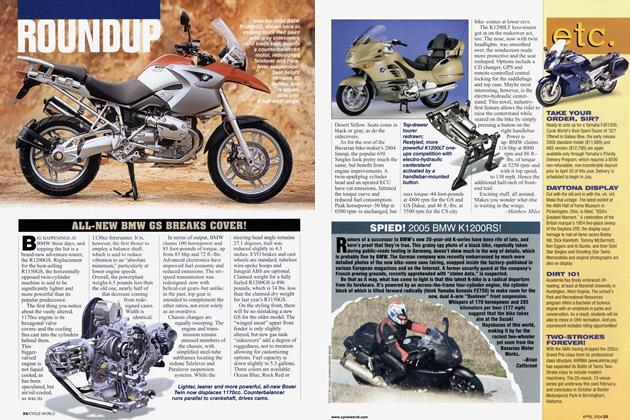

RoundupAll-New Bmw Gs Breaks Cover!

April 2004 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

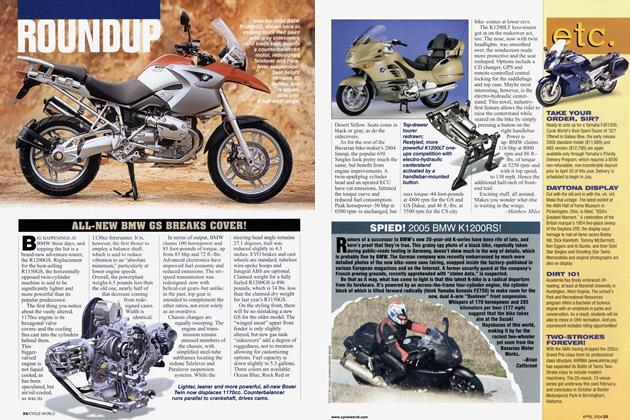

RoundupSpied! 2005 Bmw K1200rs!

April 2004 By Brian Catterson