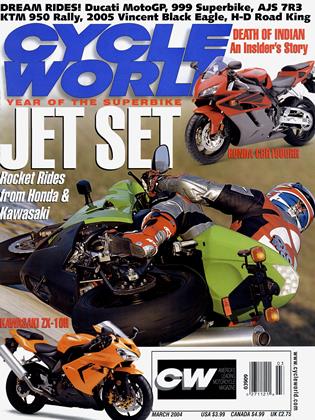

SECOND COMING

The never-ending story of Jeff Ward

BRIAN CATTERSON

RACE WATCH

EVER SEEN ON ANY SUNDAY? SURE YOU HAVE. BUT DO YOU recognize the kid wheelying the Honda Mini-Trail in the opening minutes? The answer, for those who haven't seen

On Any Sunday Revisited, is Jeff Ward. The man who would eventu ally become a seven-time national motocross and supercross champi on was just 9 years old then, but was already on the road to fame and for tune. Well, fame anyway.

"I was out at Saddleback Park, just messing around, doing some wheelies," he recalls. `There was a guy with a movie camera there, and he asked me to wheelie three or four or five more times. I had no idea who he was, and when we went to see the movie, there I was! I had no idea I was even going to be in it." Ward retired from motorcycle racing in 1992 to take up car rac ing, but returned last year to corn-

pete in the inaugural AMA Red Bull Supermoto Champi onship. Riding as fellow motocross legend Jeremy McGrath's teammate on the Troy Lee Honda squad, the scrappy veteran won no fewer than half the races that made up the six-round series, but came up short in the winner-take-all finale held in Las Vegas last November.

It's not too painful a cliché to say that Ward has ra~ing in his blood. Born on June 22, 1961, in Glasgow, Scotland, he moved along with his family to Southern California as a child, and un der the gin~'~c of his motocross and tnals-riding father Jack began racing~thini-bikes at age 6. Most motorcycle enthusiasts over the age. of 40 recall the red-headed Ward as the "Flying Freckle," racing a factory-backed Honda XR75 in the early `70s.

"Honda hired me to ride the XR75, and my dad and I had our own product line, Jeff Ward Racing Products. We were re ally competitive, even with the two-strokes for a long time af ter they came out." - -

Motocross was in its infancy then, so there wasn't any Team Green to discover the next Bubba Stewart as there is today. But Ward wound up at Kawasaki anyway, signing a deal to race 125s at the age of 16 in 1978. That led to numerous successes over the following 14 years, but what Ward remembers most was the excitement of inking that first deal. “I remember walking through the factory doors, meeting the Japanese and going into the race shop. And of course riding and training with Jimmy Weinert and Gaylon Mosier. That would be like kids today getting to ride with Stewart and Carmichael!”

Like all racers, Ward eventually grew tired, and at age 31 decided to hang up his kidney belt.

“I was getting burned out, trying to keep up with my injuries and having to re-motivate myself to fight off the young guys again the next year. I could have gone another two or three years as a topfive rider, but I wanted to go out on top ”

While the body was becoming less able, however, the mind was still willing.

“I knew I wanted to keep racing something, but mountain bikes were too much work. I did a couple of car-racing schools, and thought maybe I’d try that.

I was good friends with Paul Tracy, who ran Indycars, and he had some connections in the Indy Lights series who were able to get me some tests.”

Rare in auto-racing circles, Ward spent $130,000 of his own money to buy an

Indy Lights car, and for a while ran it in Kawasaki colors.

“I was working with Kawasaki as a consultant, helping their riders, so the money I got from that helped my car career,” he explains.

Four-time 500cc world roadracing champion Eddie Lawson was making forays into the car-racing world at the same time as Ward, and the two competed in their first Indy Lights race together at Laguna Seca at the end of the 1992 season. While Lawson went on to a briefbut-high-profile run in the established CART Indycar series, Ward migrated to the fledgling Indy Racing League, cornerstone of which is the Indianapolis 500. Ward raced at “The Brickyard” for the first time in 1997, and things couldn’t have gone better. He led 49 laps, finished third, and was voted Rookie of the Year.

By the end of the 2002 season, Ward had scored pole positions, won a race at Texas and surpassed the $4-million mark in IRL winnings. But ironically, the season in which he won his first race was also his last, as he found himself without a ride for 2003.

“Opportunities were getting thinner and thinner,” he laments. “The IRL gave

me the opportunity to race Indycars, for sure, but then Honda and Toyota came into the league, and more CART guys came over, and the smaller teams just got pushed out.”

So, a decade after he retired from motorcycle racing, Ward was again considering his options. And again, the only thing> he knew was that he still wanted to race.

That’s when he heard about supermoto.

“(Roadracer) Scott Russell was doing a race at California Speedway, and invited Troy Lee and me to a go-kart track on the Thursday before the race to check it out. We both rode his KTM, and decided to do the race that weekend. We had just one day to get our bikes converted over-we didn’t have wheels or anything.”

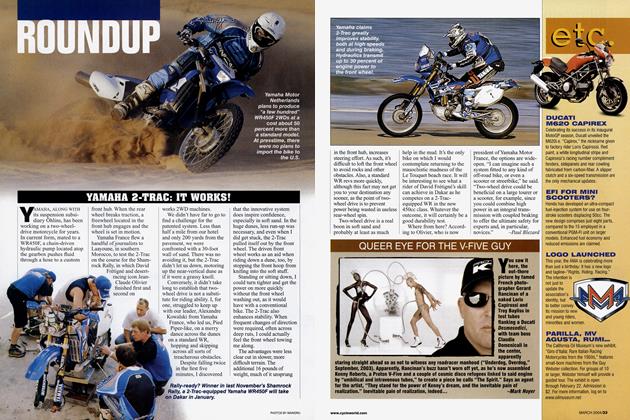

That weekend, Ward shocked onlookers by winning, passing fellow supermoto debutante McGrath on the penultimate lap and setting in motion the chain of events that led to the formation of the Troy Lee Honda team. Having heard that the AMA was planning to sanction a trial supermoto series for 2003, Lee-the “helmet painter to the stars”-quickly put together a team with Ward and McGrath,

enticing the latter to leave his then-sponsor KTM to return to Honda for the first time since 1996.

The inaugural AMA Red Bull Supermoto series was launched in conjunction with the World Superbike races at Laguna Seca in July, and Ward shocked onlookers there, too, passing early leader McGrath and then fending off perennial world motocross championship bridesmaid Kurt Nicoll of England to win again.

Where the California Speedway field had been made up predominantly of amateurs from the STTARS series, the Laguna Seca race was a veritable Who’s Who of motorcycle racing, with 138 entries from every discipline and a number of foreigners, as well. No one knew what to expect, and many attributed the allmotocrosser podium to the fact that the course featured a high percentage of dirt.

No further conclusions were gleaned from the second series round at South Boston Speedway in Virginia six weeks later, won by roadracer Doug Chandler, because rain forced the race to be postponed from Saturday to Monday, and Ward and others had prior commitments. But when Ward pulled off an amazing double-header on the weekend of Octo> ber 4-5, winning the Formula USA-sanctioned “Return of the Superbikers” in Del Mar, California, on Saturday and flying to Columbus, Ohio, overnight to win round three of the AMA series on Sunday, it could no longer be considered a fluke. The “Flying Freckle” was back, beating up on guys 10 and even 20 years his junior.

Perhaps this shouldn’t be that surprising. After all, Ward took part in all seven of the ABC-TV “Superbikers” races that gave birth to this form of racing. He quickly downplays this connection, however, not least because the last of those races took place 19 years ago!

“That was an eye-opening experience, definitely,” he recalls. “I was only 18 years old when I rode the first one, and

to hop on one of those things and go over 100 mph on roadrace tires with nothing but a chest protector on...it seems kind of stupid now, but at the time it was fun. Racing against guys like Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey was great. We always looked forward to it, but never thought that we could make a series out of it.”

The “Superbikers” races were held at Southern California’s Carlsbad Raceway on a high-speed course made up of the dragstrip, the roadrace track and a dirt section that combined equal parts dirttrack and motocross. With the exception of a few Harley-riding dirt-trackers, most competitors campaigned two-stroke 500cc motocross bikes outfitted with 19inch dirt-track tires and large, roadracestyle front disc brakes.

Today, supermoto races are held on tighter courses with much shorter dirt sections, four-strokes are favored for their tractability exiting slower corners, and hand-cut 17-inch roadracing slicks are the norm. There also has been considerable refinement in riding technique.

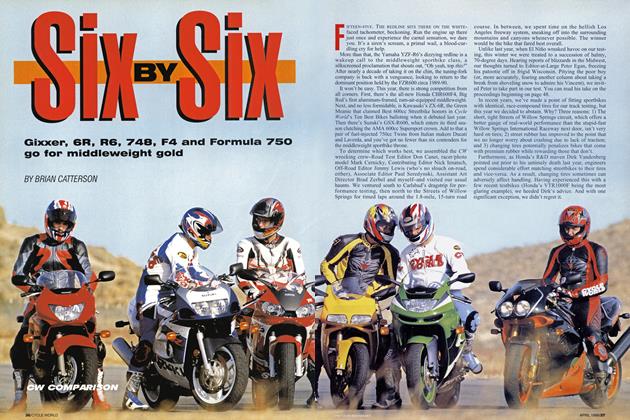

Masters of the art are the Europeans, who embraced what they originally called supermotard and made it their own. A number of the stars from the World Supermoto Championship took part in the inaugural AMA series, and Ward went to school on all of them.

“Boris Chambón and Jurgen Kunzel are two of the fastest guys over there, and they impressed me with their speed right out of the box. Their riding style helped them immensely, especially on tracks that didn’t have a lot of grip. Before, I was riding sort of roadrace-style, hanging off with my leg straight out, where now I’m sitting in the middle of the bike and using more of a dirt-track style, where you just kind of hang your leg out there. That way, you can flick the bike and use more of the rear wheel going into the corners rather than the front.

“We’ve learned a lot about bike setup from them, too. Their bikes are a lot I~higher than ours; we've got ours too low so we're dragging pegs."

Ward squared off against Chambon for the first time at round four in Dallas, Texas, in mid-Octo r, and frankly expected defeat. But pint-sized Frenchman made a rare mistake in his heat race and was forced to qualify through a semi-final, so had to start the final from the back of the grid. Jet-lagged and weary from having won the KTM Unlimited-class final a half hour prior, Chambon cut a swath to the front, but Ward put his head down and turned his fastest laps of the race to win.

Round five at Southern California’s Irwindale Speedway on November 1 marked the arrival of an even fiercer World Supermoto contender, Chambón’s KTM teammate Kunzel. With the smoke from nearby wildfires giving the air a purple hue, the German won the KTM Unlimited final and had a mind-boggling 17-second lead on the Red Bull Supermoto field when he slipped off in a dusty corner, then clipped an apex marker and snapped off his rear brake pedal. That let 1998 AMA 250cc Motocross Champion Doug Henry through to notch his first win on his Team Motodynamics Yamaha.

Ward, meanwhile, had his first “off” night, tipping over exiting the dirt section and struggling to get his CRF450R re-fired. He retired from the race and was credited with 21st place.

That set the stage for the winner-takeall finale, extravagantly produced by series sponsor Red Bull on a nearly milelong course in the parking lot of the Rio Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, and broadcast live on the Outdoor Life Network. A total of 74 riders were invited to the final after scoring points in one of the five qualifying rounds, and whoever won this night would be crowned the inaugural AMA Supermoto National Champion.

With Chambón and Kunzel both “in the house,” many were expecting a European runaway in the shadow of the replica Eiffel Tower that rose above the back straightway. So it came as a bit of a surprise when Chambón crashed violently on the second lap, and then Kunzel tangled with another rider and wound up sitting in a flowerbed! In the blink of an eye, the European threat had been eliminated.

Or had it? Leading the early laps was Alexandre Thiebault, another Frenchman who had competed in two qualifying rounds on a Carmichael Honda, but had never run up front in a final.

Thiebault led nine of the scheduled 14 laps, but then began to fade, and after a couple of preemptive passing attempts, Ward finally got by. Unbeknownst to him, however, roadracer Ben Bostrom had begun to make his move. Wearing gold Aden Ness leathers, and with a Red Bull can affixed to his helmet, the 29year-old Californian climbed from fifth to second in just four laps, and set his sights on the leader.

For the first time all season, Ward looked ragged, and onlookers sensed that this might not be his night. When Bostrom inevitably took the lead, Ward visibly wilted, as though the fire inside him had been snuffed out. Henry then> added further insult, deposing Ward to third, thus ending what had started off as a dream season.

“I could see that coming,” Ward said afterward. “Honda put a pretty good effort behind Ben, and I’d practiced with him three or four times, so I knew he was an extremely good rider. What surprised me was that he was just hanging back there. I was screwing around with

that Frenchman, going back and forth, and that let Ben catch up to us, so we were sitting ducks.”

It’s tempting to point out that if the series had been scored on a traditional points basis, Ward would have been crowned champion. But that conveniently ignores the fact that many talented racers with commitments to other series-Bostrom, for example-only competed in a

race or two. Then again, Ward missed the South Boston race himself, and didn’t score any points at Irwindale...

Be that as it may, the 2004 season will almost assuredly see the AMA Supermoto Champion determined by a traditional points-paying system. And while rumors circulate that McGrath may do only select rounds-he in fact skipped Irwindale to earn appearance money at a supercross race in Fresno-Ward says he’ll be back.

“I want to be in it, for sure,” he says. “This last year, I did to help the sport. I didn’t have to go do all those races, but if I didn’t show up, and Jeremy didn’t show up and Mike Metzger didn’t show up, there might not have been a Vegas! Nobody would have been as pumped about it.

“Jeremy, I think, was getting pretty decent money from his sponsors, but no one was going to pay me a big check to race supermoto. There’s a lot of interest in me from the factories now, though, so hopefully I’ll make some money next season.

“I’m 42 now, so I don’t know how much longer I’m going to do this. I don’t think I’m going to be out there when I’m 48, pounding down the pavement. But who knows? Even if I don’t win, it’ll be fun.” □