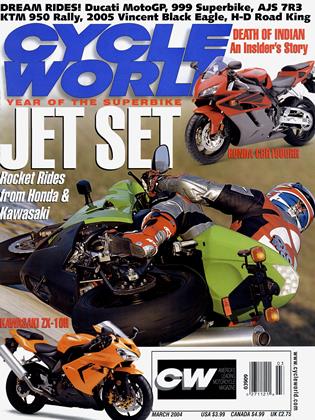

CW RIDING IMPRESSIONS

JET SET

Flight ZX-10R and CBR1000RR, cleared for takeoff

DON CANET

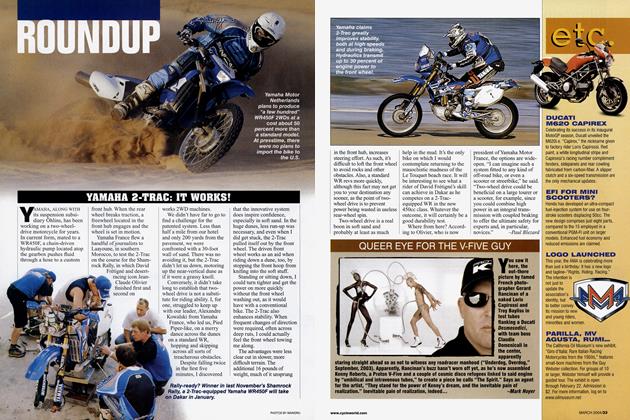

A SPORTBIKE REVOLUTION IS UPON US, AND we owe much of it to the restructuring of 500cc Grand Prix into its current MotoGP format. There’s been a changing of the guard as racing two-strokes have been smoked by the new breed of GP machine. Sportbike enthusiasts are the real winners here, with cutting-edge four-stroke technology helping shape the bikes we can now buy.

Last year’s worldwide realignment of Superbike rules-which now allow lOOOcc inline-Fours to compete in the premier class of production-based bikes-has given the factories even more incentive to pull out the stops on streetbike development. The link between works machines gracing the front row of the grid and bikes parked front and center in dealer showrooms is greater than ever.

Predictably, Suzuki’s stunning GSX-R1000 got the drop on the competition, snatching the AMA Superbike Championship in 2003. But Honda, Kawasaki and Yamaha would soon react with all-new powerhouse Fours of their own.

In December, Kawasaki and Honda each rolled out its respective 998cc inline-Four for the press to ride. Okay, so I’m one lucky s.o.b., getting to attend back-to-back launches for two of the most sensational sportbikes of the year. First,

I flew out to Florida for a day aboard Kawasaki’s ZX-10R at Homestead Miami Speedway. From there, I jetted west to Phoenix to ride Honda’s CBR1000RR at Arizona Motorsports Park.

Kawasaki boldly claims that its new Ninja possesses the best power-to-weight ratio in the class. Had Team Green Berets infiltrated the opposition’s camp and gathered topsecret intelligence? Perhaps not, but the Kawi folks did admit to using a 2003 Gixxer for target practice throughout the latter stages of ZX-10R development.

The 10R represents a wholesale departure from all Openclass Ninjas of the past 20 years. Just sitting astride this very compact machine gives you a sense of Kawasaki’s renewed commitment to uncompromised racetrack performance.

With chassis dimensions rivaling those of a 600, the 10R is miles removed from the rangy ZX-9R, and even makes the benchmark Suzuki seem bulky by comparison. The lOR’s twin-beam aluminum frame cunningly arcs its main spars

over the top of the engine rather than around its sides. The result is a slimmer waistline that brings the rider’s knees inward and allows freer side-toside movement on the bike. The riding position is aggressive with a relationship between pegs, seat and handlebars that’s ideally suited to track-attack mode. The bike’s cockpit is very compact-perhaps even more so than the ZX-6RR-and is pure business in decor, featuring the same LCD instrument pod as its smaller sibling.

As I took to the track for our first session of the day, the lOR’s linear midrange power delivery and nimble-handling chassis made easy work of getting reacquainted with the circuit. While easing up to speed, I noted that drivetrain lash wasn’t excessive, nor was engine vibration-which at freeway speeds produces a mild buzz through the bars and a slight blur in the mirrors.

Initial throttle response is a bit sudden, but on the gas, power delivery is pure nirvana. There are no flat spots or stumbles to be found, just an abundance of muscle throughout the rev range. My seat-of-the-pants assessment places the Ninja on par with Gixxer peak power (about 140 bhp), yet it feels slightly mellower and more manageable through the midrange. The meat of the power curve runs from 7000 rpm all the way to the rev limit-which cuts in at an indicated 13,800 rpm (for a literclass bike!)-offering plenty of room to play.

Apparently, Kawasaki has dissected a Yamaha, as well, employing a stacked tri-axis transmission/crankshaft layout a la YZF-R1 to shorten the engine. The benefit is greater freedom of placement in the frame to optimize the center of mass and also to buy real estate for a longer swingarm. Seems long arms are the law these days, as more manufacturers have followed the Rl’s lead. A longer swingarm has more leverage against drive-chain torque, resulting in smoother rear suspension action and improved grip.

Reading the 1OR's specs, I half-expected nervous han dling due to the 54.0-inch wheelbase and 24-degree head angle. But there's also 4.0 inches of trail working to keep things steady. While claimed dry weight is 375 pounds, a Kawasaki representative revealed the bike weighed in at a still-amazing 395 pounds with all fluids except fuel. It real ly does feel feathery on its feet, thanks in part to the 1OR's extremely lightweight, six-spoke wheel design.

Tum-in is easily initiated, even on entry into Homestead’s 120-mph first turn. Flicking through the rightleft chicane leading onto the front straight was also an exercise in grace and precision. The transition from the flat infield onto the banking provided plenty of giggles, too-either sitting back in the saddle or giving a slight tug on the bars initiated a sweet second-gear power wheelie. Woo-ha!

The ZX-lOR’s innovative front brake system contributes to the light handling. Radial-mounted Tokico four-piston, four-pad calipers provide awesome bite on a pair of smallish 300mm-diameter rotors said to produce less rotational force for lighter steering action. The rotor’s “petal” design is claimed to run cooler for improved warp resistance. I found a modest two-finger squeeze yielded excellent stopping power and remained consistent throughout each 20-minute riding session.

The 10R is also equipped with a backtorque-limiting clutch that does an excellent job of eliminating rear-wheel hop on deceleration-even when bangin’ downshifts. The GSX-R1000 could certainly benefit from such a setup.

Whether I was on the gas, on the brakes or transitioning between the two, chassis pitch always felt very controlled. The fork and shock are both equipped with top-out springs, making it seem as though the bike was setup with very little free sag.

As good as the ZX-10R may be, all is not perfect. The engine’s six-speed gearbox lacked the light action we’ve come to expect from Kawasaki sportbikes. Periodically, the shift mechanism would hang on upshifts-usually during the change from second to third-requiring a tap down on the lever to index the mechanism before a subsequent upshift could be made. This wasn’t an isolated problem either, as every journalist on hand complained of shifting difficulty. I rode 11 different ZX-1 ORs at Homestead and experienced the gearbox gremlin with each and every one. It must be noted, however, that these were pilot-production units and Kawasaki is hoping to have the problem resolved before actual production models are delivered to dealers in February.

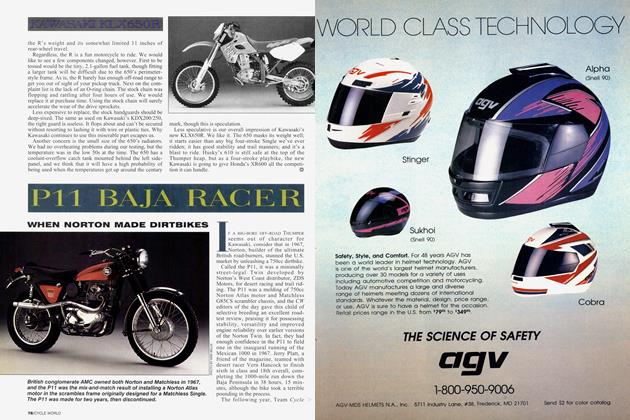

No such issues hampered the ready-for-primetime CBR1000RR that I rode two days later in Arizona. Honda’s RC211V has enjoyed unparalleled success in MotoGP, not only dominating the two-year-old series, but earning rave reviews for its ease of operation. Having personally ridden Valentino Rossi’s championship-winning bike a year ago, I can attest to its awesome performance and balanced feel. I can also say with confidence that the CBR1000RR faithfully delivers much of the same sensations I experienced aboard the RC21IV. Honda’s MotoGP program has succeeded in developing a package that hooks up, allowing earlier acceleration on corner exit than the competition. Those lessons have been applied to the CBR1000RR, as well-most evident in its Unit Pro-Link rear suspension. Mass centralization, a Honda design theme for some time now, has been taken to a whole new level. Where possible, weight is concentrated close to the bike’s roll axis for quicker, smoother steering response. Its centrally located fuel tank is a prime example of this pursuit.

While the ZX-10R is clearly an entirely new machine for Kawasaki, it may be less apparent that the CBR1000RR shares very little with last year’s CBR954RR. Its compact 998cc inline-Four is a wiped-slate design that’s both shorter and narrower than its predecessor. Notable features include a vertically stacked, cassette-type six-speed gearbox, computercontrolled ram-air system, dual-stage fuel-injection and the largest radiator I’ve ever seen on a production sportbike.

The lOOORR breathes through an elaborate two-stage airbox that routes air through a pair of small sub-ducts at low engine revs. Once into the midrange, a vacuum-operated mechanism closes the sub-ducts and opens a door allowing flow through the main ram-air duct located beneath the triple-clamp.

Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha 1000s all employ fuel-injection systems featuring primary and secondary throttle valves to help smooth throttle response and improve fuel atomization. Honda uses a single butterfly valve in each throttle body, similar to that of its MotoGP bike. The 1000RR’s dual-stage fuel-injection system locates one injector nozzle close to each intake port to ensure quick engine response in the low-rpm range, while a second showerhead injector positioned directly above the velocity stacks delivers its cool, dense charge once revs exceed 5500 rpm.

There’s also an exhaust butterfly valve located in the 4-into-2-into-1 under-and-up exhaust system that works in concert with the intake trickery to broaden power delivery

This second-generation exhaust valve doesn’t emit the annoying jingle-jangle noise we first heard on the 929.

While the CBR1000RR is less abrupt than the ZX-10R and GSX-R1000 when cracking open the throttle, room for improvement remains. Even so, the CBR conveys a feeling that a direct connection exists between the twistgrip and the rear tire’s contact patch.

Shifting gears was silky-smooth, light in effort and flawless in function. The same is true for operating any of the Honda’s controls-throttle, clutch, brakes or switches—all feeling as second nature as breathing itself. Aboard the CBR1000RR, I was able to focus more attention on the track, on hitting my marks and monitoring tire grip.

The unique steering damper found on the CBR lOOORR is just another example of Honda’s dedication to ease of operation. Any racer can attest to the confidence a firm steering damper offers at speed-one scary tank-slapper will make a believer of anyone. Slow-speed maneuvering, however, is greatly impaired. The “Honda Electronic Steering Damper”

(actually, a hydraulic unit with a servo-motor-controlled valve) automatically varies damping force according to the bike's speed and rate of acceleration. For example, cruising at 60 mph produces lighter damping than, say, whacking the throttle open at 20 mph In actual use, the system proved very effective when I landed wheelies with the front wheel cocked, and couldn’t even be felt when I performed a series of full-lock turns through the paddock.

While Honda’s claimed dry weight of 396 pounds is 26 heavier than the CBR954RR, the 1000RR offers proof that it’s how the weight is carried that’s important. Likewise, its 55.7-inch wheelbase is long by current standards, but then,

so too is the RC21 lV’s, and there’s no disputing its success With a head angle of 23.75 degrees and 4.0 inches of trail, the CBR’s handling is not quite as light as the ZX-10R, but unmatched in stability.

The Unit-Pro Link rear suspension is a key contributor to chassis stability. The upper shock mount is contained within the swingarm, rather than being attached to the frame. With this system, bump energy isn’t fed directly into the frame and thus transmitted to the steering head.

The track surface at the new Arizona Motorsports Park offered far more grip than Homestead’s polished tarmac, and the CBR’s OEM-spec Bridgestone Battlax radiais allowed deeper lean and harder cornering than I was able to achieve on the race-compound-shod Kawasaki. With the two circuits being so different, a fair comparison isn’t possible. Besides, things are just heating up, with the new YZF-R1 ’s press intro scheduled for February. And will minor updates be enough for Suzuki’s all-conquering GSX-R1000 to retain class honors for another year?

Seems a proper shootout-and as soon as possible-is our only clear course of action.