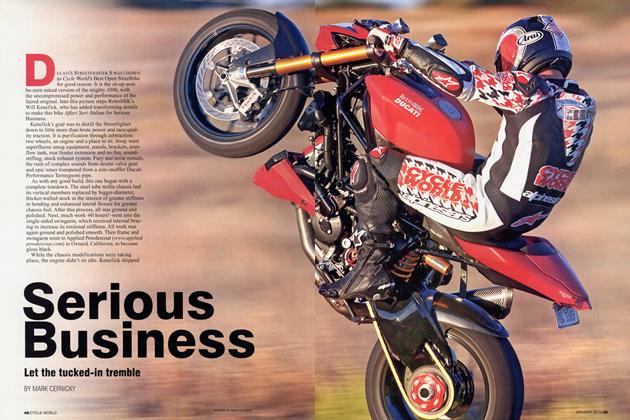

Ducati Magic

Desmo Dream Rides

“I know where the hospital is. I’ll come see ya. ”

-Kenny Roberts

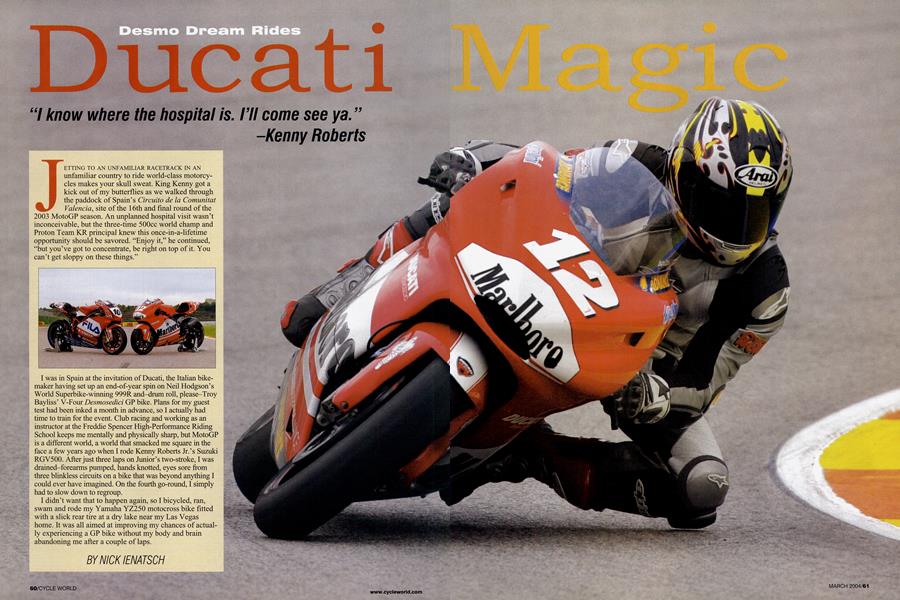

JETTING TO AN UNFAMILIAR RACETRACK IN AN unfamiliar country to ride world-class motorcycles makes your skull sweat. King Kenny got a kick out of my butterflies as we walked through the paddock of Spain’s Circuito de la Comunitat Valencia, site of the 16th and final round of the 2003 MotoGP season. An unplanned hospital visit wasn’t inconceivable, but the three-time 500cc world champ and Proton Team KR principal knew this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity should be savored. “Enjoy it,” he continued, “but you’ve got to concentrate, be right on top of it. You can’t get sloppy on these things.”

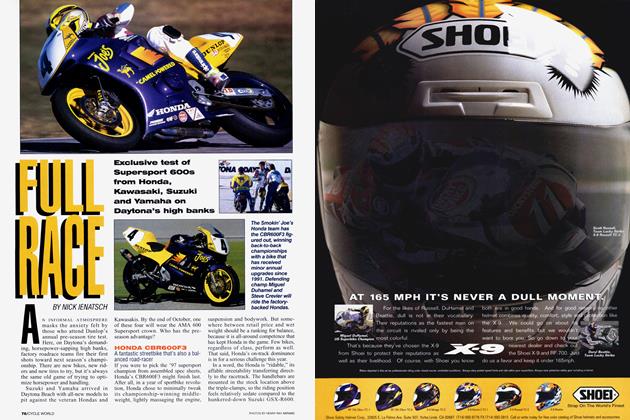

I was in Spain at the invitation of Ducati, the Italian bikemaker having set up an end-of-year spin on Neil Hodgson’s World Superbike-winning 999R and-drum roll, please-Troy Bayliss’ V-Four Desmosedici GP bike. Plans for my guest test had been inked a month in advance, so I actually had time to train for the event. Club racing and working as an instructor at the Freddie Spencer High-Performance Riding School keeps me mentally and physically sharp, but MotoGP is a different world, a world that smacked me square in the face a few years ago when I rode Kenny Roberts Jr.’s Suzuki RGV500. After just three laps on Junior’s two-stroke, I was drained-forearms pumped, hands knotted, eyes sore from three blinkless circuits on a bike that was beyond anything I could ever have imagined. On the fourth go-round, I simply had to slow down to regroup.

I didn’t want that to happen again, so I bicycled, ran, swam and rode my Yamaha YZ250 motocross bike fitted with a slick rear tire at a dry lake near my Las Vegas home. It was all aimed at improving my chances of actually experiencing a GP bike without my body and brain abandoning me after a couple of laps.

NICK IENATSCH

Riding the YZ on the dry lake was a specific exercise aimed at refining my throttle hand in a low-traction situation. When I rode Junior’s 500, my initial throttle applications were too aggressive, as the data acquisition showed. I never got in trouble, but I was on fresh rubber on a perfect day. When racing production bikes, as I did all last summer, it’s easy to be overly aggressive with the throttle, but my slickshod YZ and the tractionless lake surface were a clear illustration as to just how much more smoothly I needed to treat the throttle when riding at the limits of adhesion. Not that I was going to Valencia to purposely flirt with the edge of traction, but 230 horsepower has a way of rushing up on you...

The dry-lake training hit home during Sunday’s MotoGP event as I watched live footage from a lipstick camera posi-

tioned near the right hand of reigning series champ Valentino Rossi. So smooth was the man that it was difficult to actually see his hand move.. .as he lowered the track record! At this level, there’s no “gassing it” or “grabbing a handful,” because mistakes often lead to injury and a loss of championship points. Clearly, the world’s top racebikes, be they Superbike or MotoGP machines, require a measured touch.

"You're going to love everything about the 999. Just be careful how you move your body, or it will wobble." -Neil Hodgson

Would it be snobbish to refer to my laps aboard Hodgson’s title-winning 999R as a warm-up? I was scheduled to ride the Superbike first, as coming to grips with Valencia’s relatively tight layout would be somewhat easier on the big

Twin. Having ridden fourtime WSB champ Carl Fogarty’s 916 at Laguna Seca a few years back, I couldn’t wait to throw a leg over Hodgson’s

Fila-backed

machine. When I rode Foggy's

bike, Team Manager Virginio Ferrari was plenty happy to sit on Laguna's pit wall yapping with my wife Judy as I cir culated for more than half an hour. Not this year-the sched ule was tight and laps were few.

Despite being told that my time on the bike would be lim ited to just 15 minutes, I loafed out of the pits, weaving back and forth and testing the brakes. Some guest-testing journal ists blast out of the pits in an effort to wow the crew, but I can’t imagine doing anything that would truly impress seasoned veterans who had witnessed the year-long war between Hodgson and teammate Ruben Xaus.

Hodgson’s weight-transfer warning reminded me of the time I rode Mat Mladin’s Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750 at Willow Springs Raceway. When I scrambled across the top of the gas tank in preparation for super-fast Turn 8, my aggression was rewarded with a heart-stopping wobble. I didn’t want to repeat this experience on the Ducati, because as Hodgson told me, “When it wobbles, you can’t stay in the throttle.

You have to close the throttle or the wobble will get worse.”

As I bent the 999 into tight, lefthand Turn 2, the same comer in which Honda-mounted Nicky Hayden spun out during the race the day prior, my heart jumped into my throat. There I was, my first lap at Valencia, riding a priceless factory racebike and I was crashing! Or so I thought. Turns out, the front Michelin slick was sticking just fine, it’s just that Hodgson’s setup encourages the bike to fall into comers-and I mean fall, not unlike a 125cc GP bike.

I later discovered that Hodgson brakes really deep. “I often have my knee on the ground with the brakes still on,” he said. This helps explain his desire for the bike to flop into comers. My first time through Turn 2 was slow and sans brakes, but as my pace increased and I began to trail-brake more, the 999 became much more predictable. In fact, using the front brake holds the bike up and out of the comer, which helps control tum-in. When Hodgson finally gets off the brakes, the release helps to point the bike down the next straightaway. Valencia’s double-apex comers and wide, gradual entrances really suit this riding style. Wouldn’t you know it, Hodgson won both races at Valencia last year.

Another reason Hodgson’s bike falls into comers has to do with riding position. The Brit wraps his body around the gas tank, riding with his head and shoulders behind the windscreen, while my head and shoulders were well off the inside of the bike. A human being’s center of mass is in his shoulders, so by hanging my body off the inside of the bike, I added to the bike’s tendency to drop into the comers.

Factory Superbikes are infinitely adjustable, and Hodgson has at his disposal a mix of steeringstem offsets, shock links, differentlength gas tanks and a dozen other items that resulted in a setup that seemed exceptionally quick to a journalist who was hanging off but barely hanging on. But, hey, who’s to argue with the world champ?

Quick-steering racebikes with gobs of traction tend to be a bit nervous, and despite Hodgson’s pre-ride warning, I had a big front-straight wiggle just about the time I caught fifth gear on my third lap. Too quick in getting my butt over for fast-approaching Tum 1, and sure enough, the bike warned me with a good rappa-tap-tap, a shake significant enough to cause my body to come untucked and my

toes to curl around the footpegs. (This was nothing compared to the gyrations Hodgson rode through during races.) Wobble aside, the bike tracked straight and the initial movement didn’t become a vicious tank-slapping emergency.

All too soon, I was flagged into the pits. Few lucky souls will have the good fortune of being introduced to a world class racetrack on the world's best Superbike, but as much as I enjoyed Hodgson's 999R, the real reason I traveled to Spain was about to happen: Troy Bayliss' Desmosedici.

“Before you try any first-gear acceleration, try a few thirdand fourth-gear roll-ons. Trust me. ”

-Colin Edwards

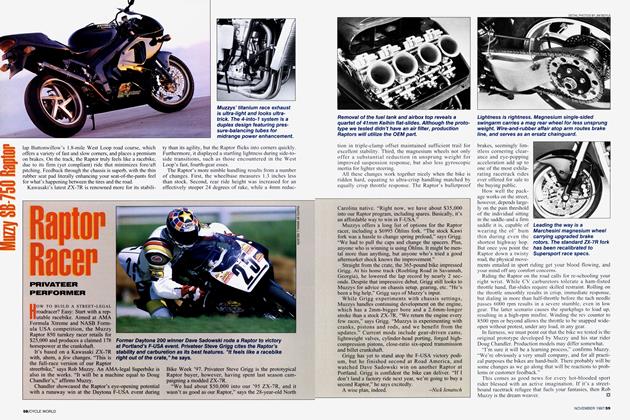

To witness the Ducati “idling” in pit lane was visceral overload. Noise-wise, it was more like a Boeing 747 at liftoff than a motorcycle. Maxing-out your television’s volume control and sitting two inches from the screen cannot begin to duplicate the experience of standing alongside the openpiped V-Four as the mechanic blipped the throttle. Since no one within a 100-foot radius could hear a spoken word, the tech raised his eyebrows and gave me a questioning thumbs-up: Was I ready? Is anyone ever ready for something like this?

Cruising through the pits earlier in the weekend was Mick Doohan. I asked the five-time 500cc title-winner for his advice on riding a MotoGP machine.

Mick didn’t exactly ease my fears. “They’re easier to ride than a twostroke,” he said. “Like a big tractor. But hey, if I

haven’t ridden one for awhile, it scares the shit out of me!”

Settling onto the thin foam seat pad, I tested the front brake lever for distance, but resisted the pressure to slam the tyke into gear and get underway. I gave the throttle a tentative twist and was taken aback by the immediate response of the fuel-injected engine.

Bayliss and I are about the same height, which helps to explain why I felt right at home. Most of my national-level racing has been on Yamaha TZ250s, and the Desmosedici shares the 250’s narrow-section gas tank. Taking a deep breath, I snicked the selector up into first gear (only racepattem shifting was offered), checked over my shoulder and began what would turn out to be a tme dream ride.

MotoGP rookie-of-the-year Hayden had warned me to make sure I got some heat in the tires before picking up the pace. “This is a fun track, but a little tight on a GP bike,” he said. “It has a good rhythm, but be a bit careful on the right side of the tire at first.”

I remembered Hayden’s advice as I headed toward Turn 3, the first right-hander. Truth be told, though, the #12 bike felt absolutely perfect, whispering to me things were okay and that I could forego any concerns over a lengthy warmup. I wish I’d felt the same way about KRJR’s RGV...

As was the case with the Suzuki, the Desmosedici wears Brembo carbon-carbon brakes. Three years ago at Phillip Island, I made the mistake of judging braking performance on my first lap, and almost put myself through the windscreen during the second go-round when the brakes got up to temperature. At Valencia, Suzuki factory rider John Hopkins advised me to drag the brakes a bit, which I did on the straightaway between Turns 1 and 2.

The difference between cold and hot carbon braKes is tne difference between plain cookie dough and momma's fresh from-the-oven brownies. At first, there simpiy isn't any stop ping power. You're scared the brakes will suddenly "come in" and spit you on your head, or cool off and fail to do their job. I learned my lesson on Junior's bike, took Hopkins' advice and halfway into the first lap had used the brakes enough to realize that every stopping system I'd sampled up to that point was a weak imitation of the latest MotoGP binders. :

There was no way in four short laps that I’d be able to ascertain maximum stopping power, but I was able to explore braking feel. Because Bayliss’ bike felt so planted, I could up my entrance speed comer after comer, reveling in the bike’s unflappable tum-in. The innate connection between the brake lever and pressure exerted on the carbon pads gave me the confidence to experiment with entry speed. It’s one thing to blindly trust a bike and toss it into a comer, it’s another to feel as if you’re guiding it to the exact line with the front brake, even if you enter the comer 2 mph faster than on the lap previous.

Unlike Hodgson’s 999R with its tendency to fall into corners, Bayliss’ bike felt completely neutral. Of course, I was running at a pace that was about 6 seconds slower than the qualifying cut-off at Valencia, and about 10 seconds slower than Bayliss had gone in qualifying. Plenty fast for me, though.

Remember the roadmnner-chasing coyote on Saturday morning cartoons? In one of his many failed attempts, the coyote winches back a huge slingshot, steps into the pocket and cuts the rope. That was me exiting Valencia’s final corner. Second gear, aim for the end of the half-mile straight and.. .HAA WWWAAZZZING! I tucked in and fired through the next four gears as fast as I could shift. There was a point where my brain would no longer accept the incredible speed.

All I could do was hope to spot the end of the pit wall, where I swapped the joy of acceleration for the near-panic of slowing and trying to backshift four gears. And compared to some of the other circuits on the MotoGP schedule, Valencia’s front straight is relatively short!

“Savor this. When you think about it, you’re testing tomorrow’s streetbikes.”

-Garry Taylor, Suzuki Team Manager

During the last two laps, heading over the third-gear hill before the final turn while hung off the left side of the bike, I spun the rear tire under power. Big deal, you say? Well, it was for me because I’m not the type of rider who does that sort of thing very often. Moreover, the consequences of crashing a GP bike during a test ride could linger for years. While the incredible power of the Ducati encourages rearwheel, dirt-track-style steering, the chassis geometry puts the rider clearly in touch with the rear contact patch and encourages even more experiments with traction. Addictive stuff! Right there, the lessons learned on the dry lake paid off.

All of this underscores the Desmosedici ’s surprising rideability. It’s actually set up like a streetbike. Unlike the 500cc two-strokes I’ve ridden, the Due’s suspension actually moved.

“I’ve got it set up to transfer weight well, to give me good traction feel,” Bayliss confirmed. “It’s a great bike to ride, really fun. Of course, getting that last 10 percent out of it is tough...”

Over the last 15 years, I’ve ridden 500cc GP bikes raced by Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey, Doohan and Roberts Jr. In each case, I got off wanting more, simply because I had ridden something I didn’t understand. I got off Bayliss’ bike wanting more, as well, but the reason was different: I could see a clear path to quicker lap times. The move to four-strokes has reignited GP racing’s premier class for fans, manufacturers and riders alike because the promise of improvement is as clear as the Desmosedici ’s voice at 16,000 rpm. O