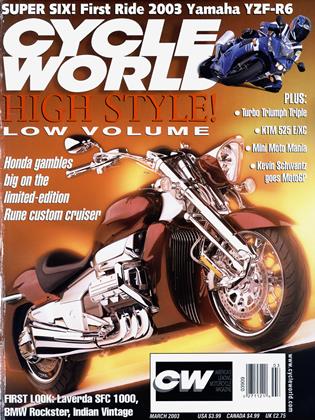

Mission Impossible?

No, just a lot of work

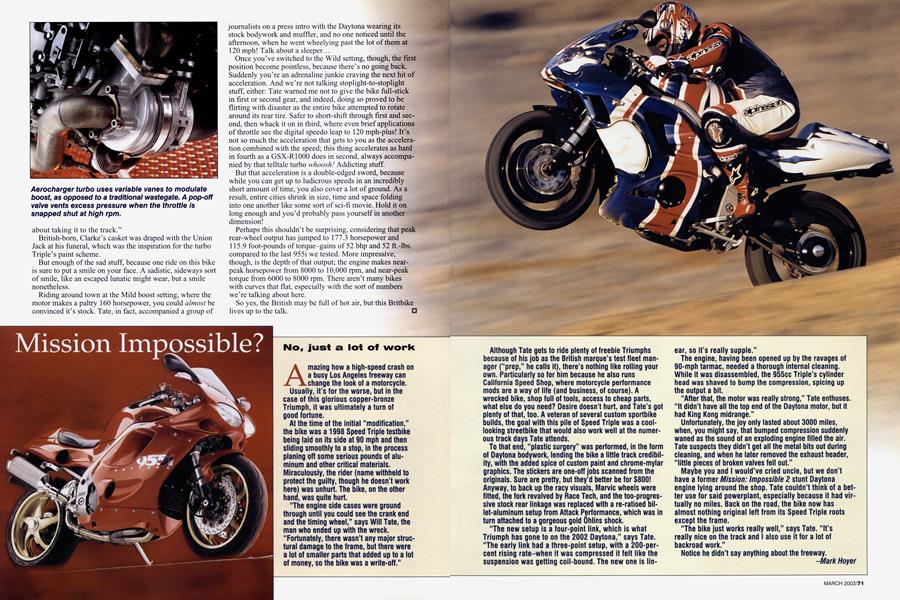

Amazinq how a hiqh-speed crash on a busy Los Angeles freeway can change the look of a motorcycle. Usually, it’s for the worse, but in the case of this glorious copper-bronze Triumph, it was ultimately a turn of good fortune.

At the time of the initial “modification,” the bike was a 1998 Speed Triple testbike being laid on its side at 90 mph and then sliding smoothly to a stop, in the process planing off some serious pounds of aluminum and other critical materials. Miraculously, the rider (name withheld to protect the guilty, though he doesn’t work here) was unhurt. The bike, on the other hand, was quite hurt.

“The engine side cases were ground through until you could see the crank end and the timing wheel,” says Will Tate, the man who ended up with the wreck. “Fortunately, there wasn’t any major structural damage to the frame, but there were a lot of smaller parts that added up to a lot of money, so the bike was a write-off.”

Although Tate gets to ride plenty of freebie Triumphs because of his job as the British marque’s test fleet manager (“prep,” he calls it), there’s nothing like rolling your own. Particularly so for him because he also runs California Speed Shop, where motorcycle performance mods are a way of life (and business, of course). A wrecked bike, shop full of tools, access to cheap parts, what else do you need? Desire doesn’t hurt, and Tate’s got plenty of that, too. A veteran of several custom sportbike builds, the goal with this pile of Speed Triple was a coollooking streetbike that would also work well at the numerous track days Tate attends.

To that end, “plastic surgery” was performed, in the form of Daytona bodywork, lending the bike a little track credibility, with the added spice of custom paint and chrome-mylar graphics. The stickers are one-off jobs scanned from the originals. Sure are pretty, but they’d better be for $800! Anyway, to back up the racy visuals, Marvic wheels were fitted, the fork revalved by Race Tech, and the too-progressive stock rear linkage was replaced with a re-ratioed billet-aluminum setup from Attack Performance, which was in turn attached to a gorgeous gold Öhlins shock.

“The new setup is a four-point link, which is what Triumph has gone to on the 2002 Daytona,” says Tate. “The early link had a three-point setup, with a 200-percent rising rate-when it was compressed it felt like the suspension was getting coil-bound. The new one is linear, so it’s really supple.”

The engine, having been opened up by the ravages of 90-mph tarmac, needed a thorough internal cleaning. While it was disassembled, the 955cc Triple’s cylinder head was shaved to bump the compression, spicing up the output a bit.

“After that, the motor was really strong,” Tate enthuses. “It didn’t have all the top end of the Daytona motor, but it had King Kong midrange.”

Unfortunately, the joy only lasted about 3000 miles, when, you might say, that bumped compression suddenly waned as the sound of an exploding engine filled the air. Tate suspects they didn’t get all the metal bits out during cleaning, and when he later removed the exhaust header, “little pieces of broken valves fell out.”

Maybe you and I would’ve cried uncle, but we don’t have a former Mission: Impossible 2 stunt Daytona engine lying around the shop. Tate couldn’t think of a better use for said powerplant, especially because it had virtually no miles. Back on the road, the bike now has almost nothing original left from its Speed Triple roots except the frame.

“The bike just works really well,” says Tate. “It’s really nice on the track and I also use it for a lot of backroad work.”

Notice he didn’t say anything about the freeway.

Mark Hoyer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

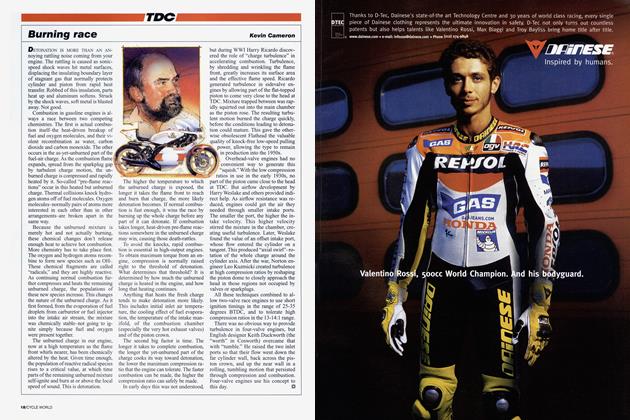

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

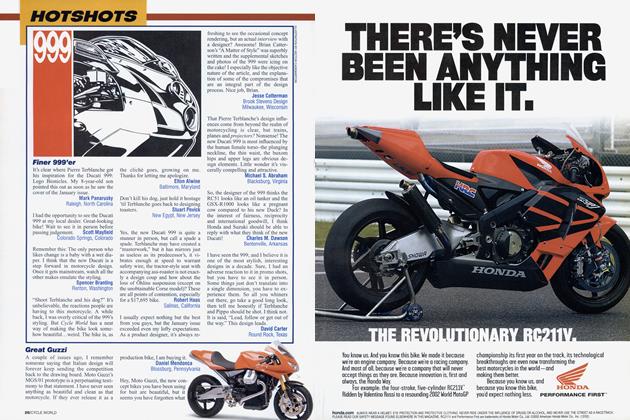

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

Roundup

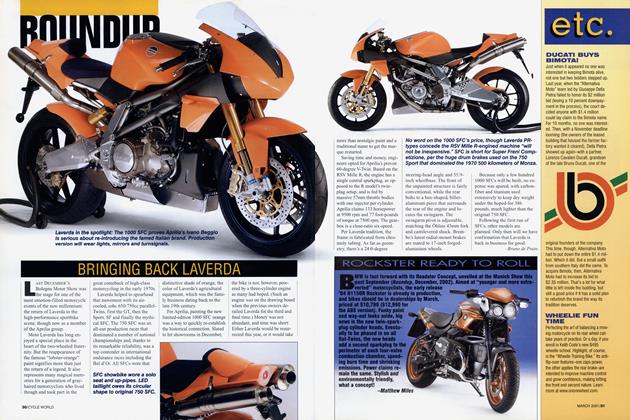

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles