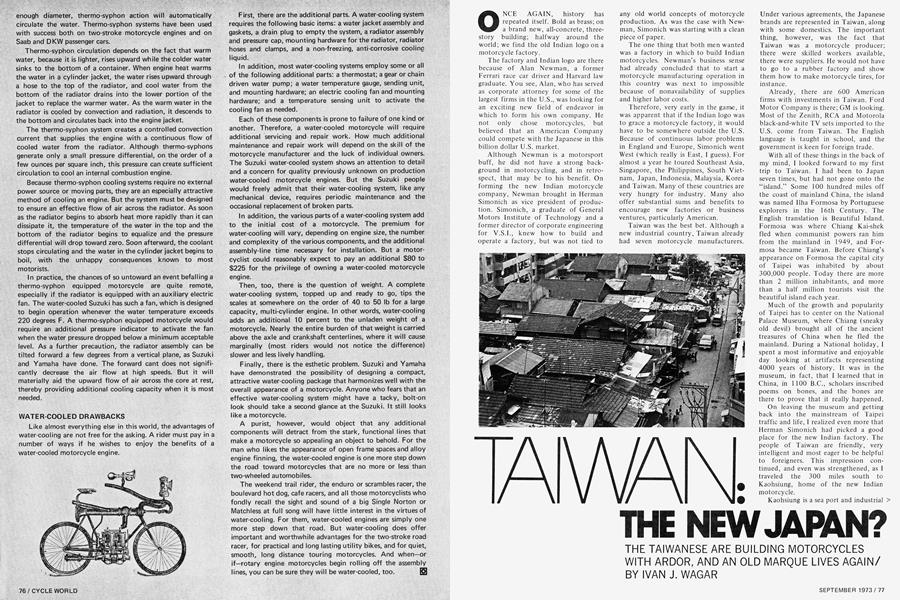

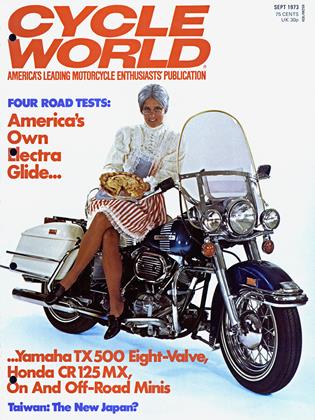

TAIWAN: THE NEW JAPAN?

THE TAIWANESE ARE BUILDING MOTORCYCLES WITH ARDOR, AND AN OLD MARQUE LIVES AGAIN

IVAN J. WAGAR

ONCE AGAIN, history has repeated itself. Bold as brass; on a brand new, all-concrete, threestory building; halfway around the world; we find the old Indian logo on a motorcycle factory.

The factory and Indian logo are there because of Alan Newman, a former Ferrari race car driver and Harvard law graduate. You see, Alan, who has served as corporate attorney for some of the largest firms in the U.S., was looking for an exciting new field of endeavor in which to form his own company. He not only chose motorcycles, but believed that an American Company could compete with the Japanese in this billion dollar U.S. market.

Although Newman is a motorsport buff, he did not have a strong background in motorcycling, and in retrospect, that may be to his benefit. On forming the new Indian motorcycle company, Newman brought in Herman Simonich as vice president of production. Simonich, a graduate of General Motors Institute of Technology and a former director of corporate engineering for V.S.I., knew how to build and operate a factory, but was not tied to any old world concepts of motorcycle production. As was the case with Newman, Simonich was starting with a clean piece of paper.

The one thing that both men wanted was a factory in which to build Indian motorcycles. Newman's business sense had already concluded that to start a motorcycle manufacturing operation in this country was next to impossible because of nonavailability of supplies and higher labor costs.

Therefore, very early in the game, it was apparent that if the Indian logo was to grace a motorcycle factory, it would have to be somewhere outside the U.S. Because of continuous labor problems in England and Europe, Simonich went West (which really is East, I guess). For almost a year he toured Southeast Asia, Singapore, the Philippines, South Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea and Taiwan. Many of these countries are very hungry for industry. Many also offer substantial sums and benefits to encourage new factories or business ventures, particularly American.

Taiwan was the best bet. Although a new industrial country, Taiwan already had seven motorcycle manufacturers.

Under various agreements, the Japanese brands are represented in Taiwan, along with some domestics. The important thing, however, was the fact that Taiwan was a motorcycle producer; there were skilled workers available, there were suppliers. He would not have to go to a rubber factory and show them how to make motorcycle tires, for instance.

Already, there are 600 American firms with investments in Taiwan. Ford Motor Company is there; GM is looking. Most of the Zenith, RCA and Motorola black-and-white TV sets imported to the U.S. come from Taiwan. The English language is taught in school, and the government is keen for foreign trade.

With all of these things in the back of my mind, I looked forward to my first trip to Taiwan. I had been to Japan seven times, but had not gone onto the "island." Some 100 hundred miles off the coast of mainland China, the island was named Ilha Formosa by Portuguese explorers in the 16th Century. The English translation is Beautiful Island. Formosa was where Chiang Kai-shek fled when communist powers ran him from the mainland in 1949, and Formosa became Taiwan. Before Chiang's appearance on Formosa the capital city of Taipei was inhabited by about 300,000 people. Today there are more than 2 million inhabitants, and more than a half million tourists visit the beautiful island each year.

Much of the growth and popularity of Taipei has to center on the National Palace Museum, where Chiang (sneaky old devil) brought all of the ancient treasures of China when he fled the mainland. During a National holiday, I spent a most informative and enjoyable day looking at artifacts representing 4000 years of history. It was in the museum, in fact, that I learned that in China, in 1100 B.C., scholars inscribed poems on bones, and the bones are there to prove that it really happened.

On leaving the museum and getting back into the mainstream of Taipei traffic and life, I realized even more that Herman Simonich had picked a good place for the new Indian factory. The people of Taiwan are friendly, very intelligent and most eager to be helpful to foreigners. This impression continued, and even was strengthened, as 1 traveled the 300 miles south to Kaohsiung, home of the new Indian motorcycle.

Kaohsiung is a sea port and industrial > center toward the south end of the island. Only a few minutes by car from the center of the modest city is an industrial zone that is quite unique: it is called a free zone. In this free zone it is possible for a manufacturer to bring supplies from other countries, install these imported parts, and then ship the finished product to some other country, without duties being paid to Taiwan.

Under this system it is possible for Indian to bring the 50cc, 74cc and 125cc engines from Minarelli in Italy into Taiwan, assemble the engines into the locally produced motorcycles, then ship the completed bikes in a foam/ cardboard box by container freight to the U.S. without taxes or duty being paid to Taiwan. By the same token, the lOOcc Fuji engines from Japan simply slip in and out of the free zone, so long as all parts that come in also go out. There are armed customs guards at the gates of the free zone to ensure that incoming items eventually become outgoing products.

Most companies require two years to get a motorized product off the assembly line; Simonich had Indians coming off the line he designed and produced in Taiwan within six months. There were a couple of problems, however. Many times throughout inital production runs the American became very annoyed that this or that part had not arrived from the supplier in time for a batch run. On questioning the Taiwanese production manager, he was always told that the parts would be there "tomorrow." In complete frustration, Herman erected a giant sign in the plant informing everyone that no longer was there such a word as "tomorrow"— it had been removed from the language! Things went well for a week. But one day some fork parts were not in their bin to supply the line. A stern vice president, behind a closed office door, demanded to know "where the hell are the parts?" After some silence, the purchasing agent finally announced, with considerable pride, that the parts would be in the plant the "day after today."

Also, the first dozen Indian motorcycles off the line at Kaohsiung featured upside down and backward Indian decals on the gas tanks. When on the carpet about that one, the production manager, in final desperation, asked Simonich if he would know which way to mount Chinese characters on a motorcycle gas tank when faced with the problem for the first time!

During the start up, Simonich spent most of his 16-hour days instructing suppliers on how to build a better product. An example was a new casting technique for lower fork legs, a method quite common in this country, but unknown in a little foundry with dirt floors and a dozen employees. Simonich taught the supplier how to make low pressure aluminum castings. As a result, with this supplier and several others, the American Simonich can just about walk on water; at least in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

An even greater reason for choosing Taiwan for the new Indian factory has to be the people of Taiwan. As touched on earlier, the people are polite and patient to a fault. Sitting in my hotel room before dinner, while making notes on the day's happenings, I noticed a little old man on the roof of the building across the street. It dawned on me that the man was cultivating trees, the little Bonsai-type tree we associate with Japan. After that I studied the man, and discovered that he had about 30 trees in individual pots. Each day he would spend about half an hour on each plant, bending, tying or trimming each branch in a certain way. Although he was a football field away, and we never spoke, it became very apparent that it was a labor of love.

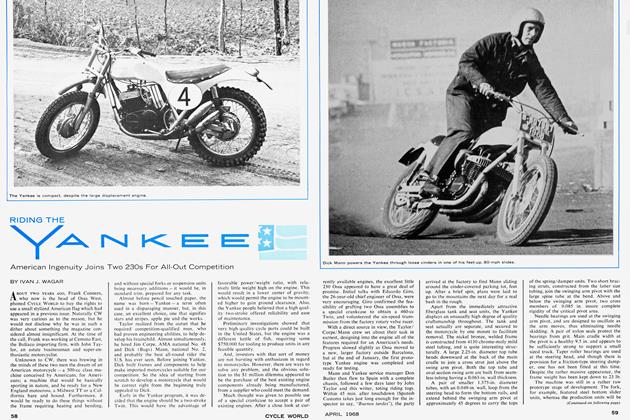

I saw the same devotion in production when I went to the Indian factory. At the time the production line was fully stocked for the target quota of 2000 units for the month, but plant engineer Lin insisted that I see the tire mounting machine. "We mount tires in less than 20 seconds," was the proud statement from Lin. Not long after, a 16-year-old boy proudly whipped off his shoes, grabbed a wheel, an inner tube and a tire, threw the whole lot on the floor and put the tire on the wheel with his bare feet! On the second go around I set my stop watch and he did, indeed, put a tire on the rim in 18 seconds. It does help, however, when we realize that Taiwan tires are made from natural rubber and therefore are softer than tires constructed from synthetic compounds.

From the pleasant secretarial greetings on entering the plant to the indepth engineering explanations by engineer Lin, it almost is possible to imagine that you really are talking to people from the Indian factory. It was from Lin, in fact, that I learned that Harley-Davidson had been looking for a plant and chief engineer in the Kaohsiung free industry area. Lin was offered a job, but maybe he has contacted the old Indian fever: "Indians are good, Harleys are bad."

Quite possibly Lin might also see the future of Indian programs. Die cast tooling already has been ordered from the machinery division of Toyo Kogyo (Mazda) for Indian's own engine to be produced in Taiwan in 125 and 175cc form. The new engine already has undergone two years of testing in the U.S., utilizing sand cast engine cases, and durability does not appear to be a problem. Unlike previous imports from Taiwan, all current and future Indians are designed and tested in the U.S., before going into production at the new factory. Simonich runs 100 percent quality control on all domestically produced parts and subassemblies, and explains that suppliers now are sending only the best parts to Indian and the rejects to other motorcycle companies.

The first all-Indian designed engine will be a fairly straightforward piston port Single. Originally designed as a 175cc engine, the "shrunk" 125cc version will appear on the market first, and should be strong as a horse. A unique feature will be a roller-type thrust bearing on the crankshaft drive side, which will be mounted behind the primary drive gear, in the primary drive case, and lubricated by splash from the primary gears.

Benefits from such an arrangement are that frictional loadings are reduced, thus cutting down on heat and power loss. Another major advantage is a remarkable drop in engine vibration. In conventional engines, without a roller thrust bearing, side loadings on the crank must be handled by a ball bearing. While a ball bearing does a very good job of locating the crank within the cases, there are considerable, and vary ing, side pressures applied to the bearing throughout the engine cycle. All of this back and forth effort on the crank adds up to vibration somewhere in the total system.

Incorporating the roller thrust bearing will add slightly to the cost. But, as Newman points out, there are detail things that can be done to improve the machine because of the low cost of Taiwanese labor; things that could not be done if the machine were built here.

- The new Indian should be arriving in this country in September. But Indian's really big surprise is yet to come. There will be a big bore Multi, that we may see within the next year. Indian is serious, and the future should be very interesting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue