UP FRONT

Ex-files

David Edwards

IT HAS NOT BEEN A GOOD YEAR FOR START-UP motorcycle companies. First Cannondale, makers of truly innovative fuel-injected dirtbikes, went nubblies-up. Now the news that after four years of a difficult, fits-and-starts resurrection, the grand old Indian nameplate is, once again, gone. Company officials, lacking the “eight-figure funding” to go on, pulled the plug.

As Indian was going under, a book sat on my desk. Just published by Union Hill Press, Riding the American Dream is the story of Excelsior-Henderson Motorcycles, another failed restart of an early American bike. It was penned by company co-founder Dan Hanlon.

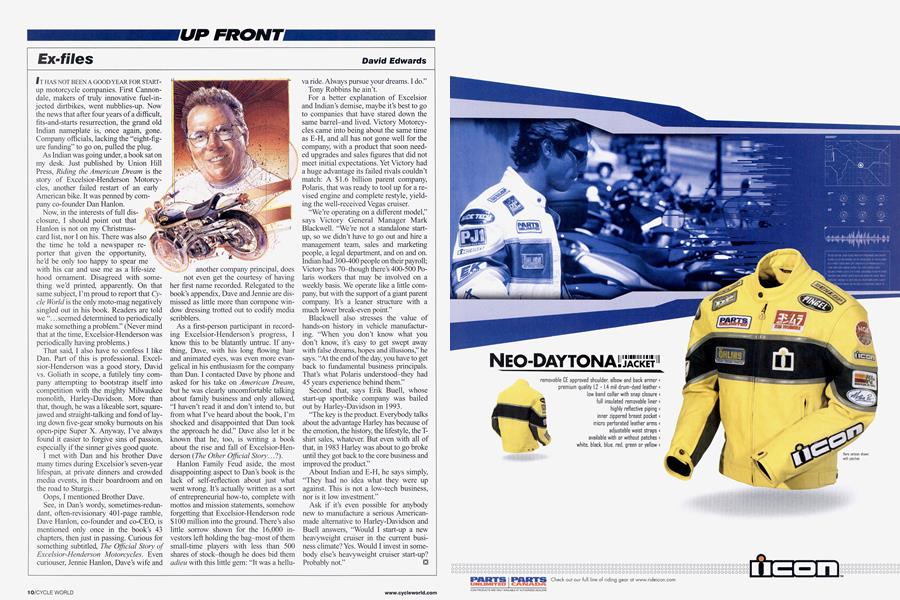

Now, in the interests of full disclosure, I should point out that Hanlon is not on my Christmascard list, nor I on his. There was also the time he told a newspaper reporter that given the opportunity, he’d be only too happy to spear me with his car and use me as a life-size hood ornament. Disagreed with something we’d printed, apparently. On that same subject, I’m proud to report that Cycle World is the only moto-mag negatively singled out in his book. Readers are told we “.. .seemed determined to periodically make something a problem.” (Never mind that at the time, Excelsior-Henderson was periodically having problems.)

That said I also have to confess I like Dan. Part of this is professional. Excelsior-Henderson was a good story, David vs. Goliath in scope, a futilely tiny company attempting to bootstrap itself into competition with the mighty Milwaukee monolith, Harley-Davidson. More than that, though, he was a likeable sort, squarejawed and straight-talking and fond of laying down five-gear smoky burnouts on his open-pipe Super X. Anyway, I’ve always found it easier to forgive sins of passion, especially if the sinner gives good quote.

I met with Dan and his brother Dave many times during Excelsior’s seven-year lifespan, at private dinners and crowded media events, in their boardroom and on the road to Sturgis...

Oops, I mentioned Brother Dave.

See, in Dan’s wordy, sometimes-redundant, often-revisionary 401-page ramble, Dave Hanlon, co-founder and co-CEO, is mentioned only once in the book’s 43 chapters, then just in passing. Curious for something subtitled, The Official Story of Excelsior-Henderson Motorcycles. Even curiouser, Jennie Hanlon, Dave’s wife and another company principal, does not even get the courtesy of having her first name recorded. Relegated to the book’s appendix, Dave and Jennie are dismissed as little more than compone window dressing trotted out to codify media scribblers.

As a first-person participant in recording Excelsior-Henderson’s progress, I know this to be blatantly untrue. If anything, Dave, with his long flowing hair and animated eyes, was even more evangelical in his enthusiasm for the company than Dan. I contacted Dave by phone and asked for his take on American Dream, but he was clearly uncomfortable talking about family business and only allowed, “I haven’t read it and don’t intend to, but from what I’ve heard about the book, I’m shocked and disappointed that Dan took the approach he did.” Dave also let it be known that he, too, is writing a book about the rise and fall of Excelsior-Henderson {The Other Official Story...?).

Hanlon Family Feud aside, the most disappointing aspect to Dan’s book is the lack of self-reflection about just what went wrong. It’s actually written as a sort of entrepreneurial how-to, complete with mottos and mission statements, somehow forgetting that Excelsior-Henderson rode $100 million into the ground. There’s also little sorrow shown for the 16,000 investors left holding the bag-most of them small-time players with less than 500 shares of stock-though he does bid them adieu with this little gem: “It was a helluva ride. Always pursue your dreams. I do.”

Tony Robbins he ain’t.

For a better explanation of Excelsior and Indian’s demise, maybe it’s best to go to companies that have stared down the same barrel-and lived. Victory Motorcycles came into being about the same time as E-H, and all has not gone well for the company, with a product that soon needed upgrades and sales figures that did not meet initial expectations. Yet Victory had a huge advantage its failed rivals couldn’t match: A $1.6 billion parent company, Polaris, that was ready to tool up for a revised engine and complete restyle, yielding the well-received Vegas cruiser.

“We’re operating on a different model,” says Victory General Manager Mark Blackwell. “We’re not a standalone startup, so we didn’t have to go out and hire a management team, sales and marketing people, a legal department, and on and on. Indian had 300-400 people on their payroll; Victory has 70-though there’s 400-500 Polaris workers that may be involved on a weekly basis. We operate like a little company, but with the support of a giant parent company. It’s a leaner structure with a much lower break-even point.”

Blackwell also stresses the value of hands-on history in vehicle manufacturing. “When you don’t know what you don’t know, it’s easy to get swept away with false dreams, hopes and illusions,” he says. “At the end of the day, you have to get back to fundamental business principals. That’s what Polaris understood-they had 45 years experience behind them.”

Second that, says Erik Buell, whose start-up sportbike company was bailed out by Harley-Davidson in 1993.

“The key is the product. Everybody talks about the advantage Harley has because of the emotion, the history, the lifestyle, the Tshirt sales, whatever. But even with all of that, in 1983 Harley was about to go broke until they got back to the core business and improved the product.”

About Indian and E-H, he says simply, “They had no idea what they were up against. This is not a low-tech business, nor is it low investment.”

Ask if it’s even possible for anybody new to manufacture a serious Americanmade alternative to Harley-Davidson and Buell answers, “Would I start-up a new heavyweight cruiser in the current business climate? Yes. Would I invest in somebody else’s heavyweight cruiser start-up? Probably not.” □