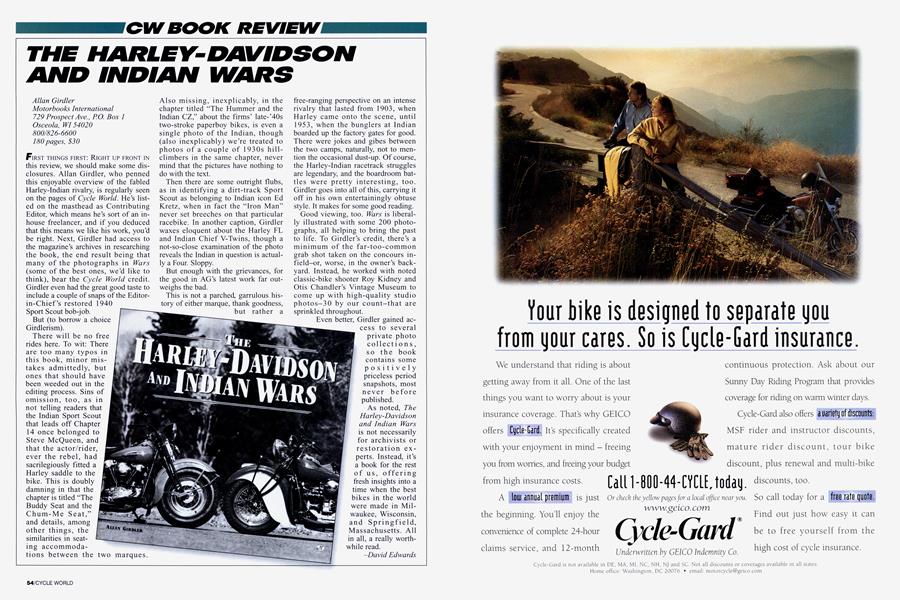

THE HARLEY-DAVIDSON AND INDIAN WARS

CW BOOK REVIEW

Allan Girdler Motorbooks International 729 Prospect Ave., P0. Box 1 Osceola, WI 54020 800/826-6600 180 pages, $30

FIRST THINGS FIRST: RIGHT UP FRONT IN this review, we should make some disclosures. Allan Girdler, who penned this enjoyable overview of the fabled Harley-Indian rivalry, is regularly seen on the pages of Cycle World. He's listedon the masthead as Contributing Editor, which means he's sort of an in-house freelancer, and if you deduced that this means we like his work, you'd be right. Next, Girdler had access to the magazine's archives in researching r the book, the end result being that r many of the photographs in Wars 1 (some of the best ones, we'd like to think), bear the Cycle World credit. t Girdler even had the great good taste to `~ include a couple of snaps of the Editor in-Chief's restored 1940 Sport Scout bob-job

But (to borrow a choice Girdlerism).

There will be no free rides here. To wit: There are too many typos in this book, minor mistakes admittedly, but ones that should have been weeded out in the editing process. Sins of omission, too, as in not telling readers that the Indian Sport Scout that leads off Chapter 14 once belonged to Steve McQueen, and that the actor/rider, ever the rebel, had sacrilegiously fitted a Harley saddle to the bike. This is doubly damning in that the chapter is titled “The Buddy Seat and the Chum-Me Seat,” and details, among other things, the similarities in seating accommodations between the two marques.

Also missing, inexplicably, in the chapter titled “The Hummer and the Indian CZ,” about the firms’ late-’40s two-stroke paperboy bikes, is even a single photo of the Indian, though (also inexplicably) we’re treated to photos of a couple of 1930s hillclimbers in the same chapter, never mind that the pictures have nothing to do with the text.

Then there are some outright flubs, as in identifying a dirt-track Sport Scout as belonging to Indian icon Ed Kretz, when in fact the “Iron Man” never set breeches on that particular racebike. In another caption, Girdler waxes eloquent about the Harley FL and Indian Chief V-Twins, though a not-so-close examination of the photo reveals the Indian in question is actually a Four. Sloppy.

But enough with the grievances, for the good in AG’s latest work far outweighs the bad.

This is not a parched, garrulous history of either marque, thank goodness, but rather a

free-ranging perspective on an intense rivalry that lasted from 1903, when Harley came onto the scene, until 1953, when the bunglers at Indian boarded up the factory gates for good. There were jokes and gibes between the two camps, naturally, not to mention the occasional dust-up. Of course, the Harley-Indian racetrack struggles are legendary, and the boardroom battles were pretty interesting, too. Girdler goes into all of this, carrying it off in his own entertainingly obtuse style. It makes for some good reading.

Good viewing, too. Wars is liberally illustrated with some 200 photographs, all helping to bring the past to life. To Girdler’s credit, there’s a minimum of the far-too-common grab shot taken on the concours infield-or, worse, in the owner’s backyard. Instead, he worked with noted classic-bike shooter Roy Kidney and Otis Chandler’s Vintage Museum to come up with high-quality studio photos-30 by our count-that are sprinkled throughout.

Even better, Girdler gained access to several private photo collecti ons, so the book contains some positively priceless period snapshots, most never before published.

As noted, The Harley-Davidson and Indian Wars is not necessarily for archivists or restoration experts. Instead, it’s a book for the rest of us, offering fresh insights into a time when the best bikes in the world were made in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Springfield, Massachusetts. All in all, a really worthwhile read.

David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

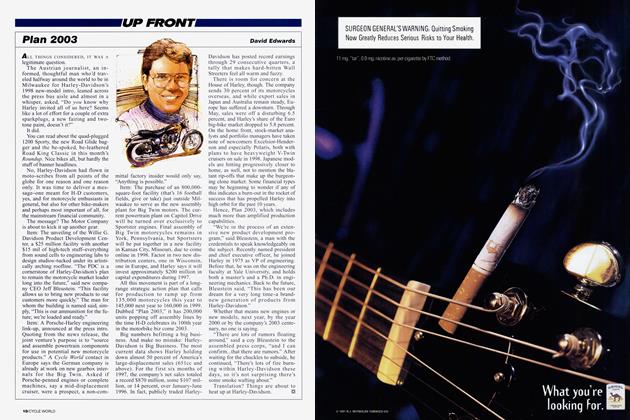

Up FrontPlan 2003

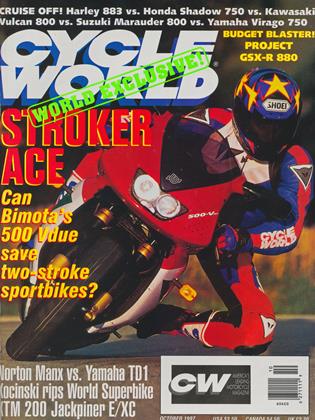

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

Roundup

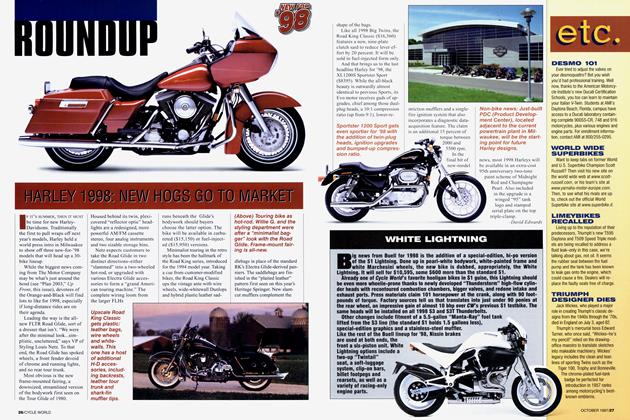

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

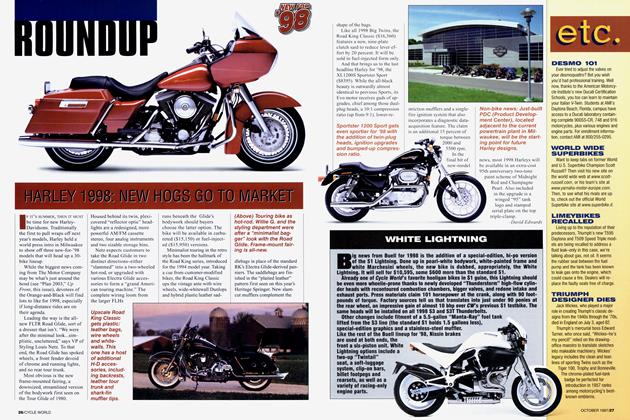

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997