TDC

Keeping Chains Alive

KEVIN CAMERON

I’VE BEEN DOING A BIT OF READING lately, and a few things have assembled themselves into possible answers for questions I’ve had for years.

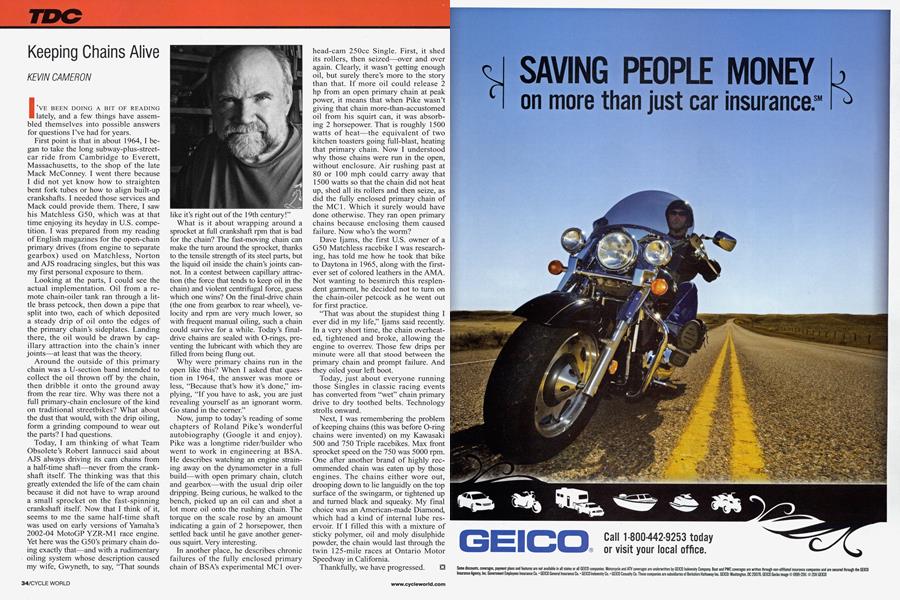

First point is that in about 1964, I began to take the long subway-plus-streetcar ride from Cambridge to Everett, Massachusetts, to the shop of the late Mack McConney. I went there because I did not yet know how to straighten bent fork tubes or how to align built-up crankshafts. I needed those services and Mack could provide them. There, I saw his Matchless G50, which was at that time enjoying its heyday in U.S. competition. I was prepared from my reading of English magazines for the open-chain primary drives (from engine to separate gearbox) used on Matchless, Norton and AJS roadracing singles, but this was my first personal exposure to them.

Looking at the parts, I could see the actual implementation. Oil from a remote chain-oiler tank ran through a little brass petcock, then down a pipe that split into two, each of which deposited a steady drip of oil onto the edges of the primary chain’s sideplates. Landing there, the oil would be drawn by capillary attraction into the chain’s inner joints—at least that was the theory.

Around the outside of this primary chain was a U-section band intended to collect the oil thrown off by the chain, then dribble it onto the ground away from the rear tire. Why was there not a full primary-chain enclosure of the kind on traditional streetbikes? What about the dust that would, with the drip oiling, form a grinding compound to wear out the parts? I had questions.

Today, I am thinking of what Team Obsolete’s Robert Iannucci said about AJS always driving its cam chains from a half-time shaft—never from the crankshaft itself. The thinking was that this greatly extended the life of the cam chain because it did not have to wrap around a small sprocket on the fast-spinning crankshaft itself. Now that I think of it, seems to me the same half-time shaft was used on early versions of Yamaha’s 2002-04 MotoGP YZR-M1 race engine. Yet here was the G50’s primary chain doing exactly that—and with a rudimentary oiling system whose description caused my wife, Gwyneth, to say, “That sounds like it’s right out of the 19th century!”

What is it about wrapping around a sprocket at full crankshaft rpm that is bad for the chain? The fast-moving chain can make the turn around the sprocket, thanks to the tensile strength of its steel parts, but the liquid oil inside the chain’s joints cannot. In a contest between capillary attraction (the force that tends to keep oil in the chain) and violent centrifugal force, guess which one wins? On the final-drive chain (the one from gearbox to rear wheel), velocity and rpm are very much lower, so with frequent manual oiling, such a chain could survive for a while. Today’s finaldrive chains are sealed with O-rings, preventing the lubricant with which they are filled from being flung out.

Why were primary chains run in the open like this? When I asked that question in 1964, the answer was more or less, “Because that’s how it’s done,” implying, “If you have to ask, you are just revealing yourself as an ignorant worm. Go stand in the comer.”

Now, jump to today’s reading of some chapters of Roland Pike’s wonderful autobiography (Google it and enjoy). Pike was a longtime rider/builder who went to work in engineering at BSA. He describes watching an engine straining away on the dynamometer in a full build—with open primary chain, clutch and gearbox—with the usual drip oiler dripping. Being curious, he walked to the bench, picked up an oil can and shot a lot more oil onto the rushing chain. The torque on the scale rose by an amount indicating a gain of 2 horsepower, then settled back until he gave another generous squirt. Very interesting.

In another place, he describes chronic failures of the fully enclosed primary chain of BSA’s experimental MCI overhead-cam 250cc Single. First, it shed its rollers, then seized—over and over again. Clearly, it wasn’t getting enough oil, but surely there’s more to the story than that. If more oil could release 2 hp from an open primary chain at peak power, it means that when Pike wasn’t giving that chain more-than-accustomed oil from his squirt can, it was absorbing 2 horsepower. That is roughly 1500 watts of heat—the equivalent of two kitchen toasters going full-blast, heating that primary chain. Now I understood why those chains were run in the open, without enclosure. Air rushing past at 80 or 100 mph could carry away that 1500 watts so that the chain did not heat up, shed all its rollers and then seize, as did the fully enclosed primary chain of the MCI. Which it surely would have done otherwise. They ran open primary chains because enclosing them caused failure. Now who’s the worm?

Dave Ijams, the first U.S. owner of a G50 Matchless racebike I was researching, has told me how he took that bike to Daytona in 1965, along with the firstever set of colored leathers in the AMA. Not wanting to besmirch this resplendent garment, he decided not to turn on the chain-oiler petcock as he went out for first practice.

“That was about the stupidest thing I ever did in my life,” Ijams said recently. In a very short time, the chain overheated, tightened and broke, allowing the engine to overrev. Those few drips per minute were all that stood between the primary chain and prompt failure. And they oiled your left boot.

Today, just about everyone running those Singles in classic racing events has converted from “wet” chain primary drive to dry toothed belts. Technology strolls onward.

Next, I was remembering the problem of keeping chains (this was before O-ring chains were invented) on my Kawasaki 500 and 750 Triple racebikes. Max front sprocket speed on the 750 was 5000 rpm. One after another brand of highly recommended chain was eaten up by those engines. The chains either wore out, drooping down to lie languidly on the top surface of the swingarm, or tightened up and turned black and squeaky. My final choice was an American-made Diamond, which had a kind of internal lube reservoir. If I filled this with a mixture of sticky polymer, oil and moly disulphide powder, the chain would last through the twin 125-mile races at Ontario Motor Speedway in California.

Thankfully, we have progressed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

AUGUST 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSometimes You Win

AUGUST 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupGet Healthy, Ride A Motorcycle

AUGUST 2011 By Philippe Devos -

Roundup

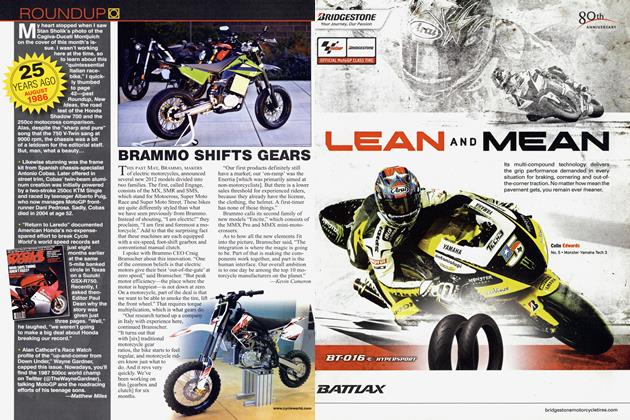

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1986

AUGUST 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBrammo Shifts Gears

AUGUST 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupOff the Reservation

AUGUST 2011 By Marc Cook