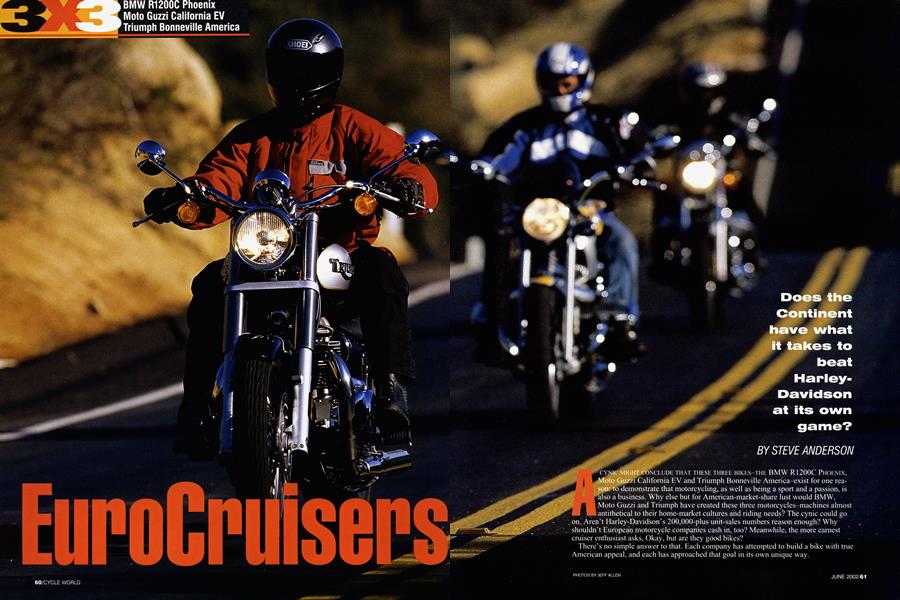

EuroCruisers

Does the Continent have what it takes to beat HarleyDavidson at its own game?

STEVE ANDERSON

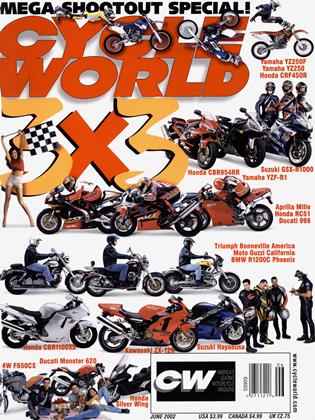

ACYNIC MIGHT CONCLUDE THAT THESE THREE BIKES-THE BMW R1200C PHOENIX, Moto Guzzi California EV and Triumph Bonneville America-exist for one reason: to demonstrate that motorcycling, as well as being a sport and a passion, is also a business. Why else but for American-market-share lust would BMW, Moto Guzzi and Triumph have created these three motorcycles-machines almost antithetical to their home-market cultures and riding needs? The cynic could go on. Aren’t Harley-Davidson’s 200,000-plus unit-sales numbers reason enough? Why shouldn’t European motorcycle companies cash in, too? Meanwhile, the more earnest cruiser enthusiast asks, Okay, but are they good bikes?

There’s no simple answer to that. Each company has attempted to build a bike with true American appeal, and each has approached that goal in its own unique way.

BMW R1200C PHOENIX

$15,100

The Moto Guzzi, for instance, harbors a sporty Italian soul in its cruiser garb. Its beefy fork tubes and gold Brembo brake calipers whisper perform-

ance, and its engine delivers on the hint. The old tractor powerplant has been tuned and fuel-injected so well that it outperforms far newer competitors. It pulls hard from 2000 rpm, cylinders throbbing and intake honking, and just gets stronger as it revs out, feeling downright sporty above 7000 rpm. The air-cooled, longitudinal 90-degree V-Twin pulls the big Guzzi though the quarter-mile in 13.48 seconds and to a top speed of 119 mph. It’s appealing in all the best V-Twin ways, and with an Italian polish that tells you the original designer did good picking this engine configuration almost four decades ago.

Guzzi’s move into the Aprilia family has also meant more resources and a stronger emphasis on quality, and many of the California’s changes this year reflect that shift. The exhaust headers are larger and better insulated to eliminate chrome discoloration, the mufflers are stainless-steel, and the new wire-spoked wheels use chrome-plated aluminum rims that mount spoke nipples on the outer flange, allowing tubeless operation-just as on the Aprilia CapoNord.

Five years ago, the Guzzi fomia’s combination of cruiser style and performance

was enough to capture the leading role in a CW cruiser comparison, beating the best from Japan and America-which tells you how much the world has changed since then. Now, the California’s performance pales compared to that of the Honda VTX1800 or the Yamaha Road Star Warrior, and it fails to separate the Guzzi from stock Harley Big Twins-let alone kitted ones. And as other cruisers have upped the ante on engine performance, the Guzzi still offers a semicramped riding position especially for plus-6-footers: hands high, torso leaned back slightly, knees high and legs bent because the floorboards are too close and the jutting cylinders prevent a rider from stretching his legs well forward. And the heel-and-toe shifter requires a conscious foot lift on every shift. You can’t help riding the Moto Guzzi without feeling that many of these components, this engine, want a happier, sportier home. The Triumph Bonneville America harks back to real roots—even if the current Triumph shares only a name with its predecessor. For the Bonneville America really is a chopped Triumph Twin, a machine whose form was defined by Sixties customizers back when the first FX Super Glide wasn’t even a sketch on the back of one of Willie G’s high-school note-

books. Just look at how it sits: low in the back on the fat 15inch rear tire, fork tubes raked out at 33.3 degrees, the 18-inch front tire way out there. No, this is one machine that looks as if it rode right off the set of a Roger Gorman biker movie.

Once you get past the look, the Triumph pleases in some ways, disappoints in others. Its 790cc parallel-Twin, with its 270-degree crank and counterbalancers, is notably smooth and torquey, and is coupled to a slick-shifting gearbox. But it’s certainly no powerhouse, as proved by the 15.12-second, 85-mph quarter-mile and 100-mph top speed. (If you’re looking for Sixties references, a Honda CB350 was roughly that quick and fast 33 years ago.) Perhaps because of flexy brake calipers, the single-disc stoppers on both ends of the Bonneville connect to a soggy lever and pedal. Don’t try two-finger braking on this one; you’ll bottom the lever on your other fingers long before the tire is anywhere near lock-up. The suspension, too, is on the soft side-but at least it presents a reasonable ride. Where does all this leave Triumph’s B-A? Looking the part of a Wild One while per-

MOTO GUZZI CALIFORNIA EV

$11,990

forming like a mild one. That’s a formula that has sold a few hundred thousand 883 Sportsters, and it made the Triumph at least one tester’s favorite in this comparison.

The BMW R1200C Phoenix, in contrast, harks back to no Sixties visions-though there must have been some acidinfluenced college professor somewhere who used a torch to carve a Captain America-replica R69. Instead, the R1200 comes from some alternative universe, one where modem BMW stylists design bold, new motorcycles for the 1939 World’s Fair. It combines forms both modem-the frame as bracket and oil-cooler duct-and streamline modeme-the organic front swingarm and chromed sidecovers-to create a machine like no other.

The Phoenix version of the R 1200C is one of five offered, and strives to be sportier than the others. A new handlebar bend places the rider just slightly back from upright, in a position both more in control and more comfortable than the original 1200’s more extreme bar. An asymmetrical tinted flyscreen actually diverts some wind from the rider’s chest. Neither pillion pad nor passenger pegs are fitted stock, but anti-lock brakes are provided. The bright yellow paint of the Phoenix adds to the visual statement-perhaps BMW could see to fit such an extrovert color to the RI 150R, as well?

The BMW’s 1170cc engine moves Chevy-V-Eight-sized, almost 4-inch pistons through a 73mm stroke-and reminds that vibration does increase with displacement. BMW’s Cmodels vibrate more than its other, slightly smaller Boxers, and fairly continuously across the rev range, though the shaking is only a light buzz by solid-mounted Harley Softail standards. BMW engineers have tuned the big Twin for bottom end, and the best pull comes from just above idle to about 4500 rpm. With lighter flywheels than most cruiser powerplants, the BMW revs quickly and charges hard from low speeds, but runs a little short of breath as the revs increase-hence the 13.88-second quarter-mile, which is slower than that of the Guzzi, and slower than the BMW feels in everyday riding.

The lack of BMW’s Paralever rear suspension may seem retrograde on the R1200, but a very long swingarm reduces the shaft-drive-related rear suspension jacking effect to much less than that of the old pushrod Boxers, all while looking much simpler and cleaner than the multi-jointed Paralever. On a backroad, the 1200 handles well by cruiser

TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE AMERICA

$7999

standards, and only gets a little wonky at about the time hard parts are starting to drag. On the highway, a good seat, a

pleasant riding position and the little BMW amenities add up-or in our continuing plea, why don’t all motorcycles come with heated handgrips? Of course, for the $15,100 pricetag of the Phoenix, amenities are expected.

And while the BMW offers the best trade-off of performance and style of the motorcycles in this comparison, its price does suggest what a tightrope the European cruisermakers are walking. At more than $15K and nearly $12K, respectively, the BMW and Guzzi are treading firmly into Harley territory-and the latest Dynas and Softail Deuces are awfully refined cruisers with which to be competing. The Triumph, in contrast, offers its own unique look and an exceptionally low price at $7999, but the performance comparison here is 883, not Big Twin.

In the end, then, these Euro Cruisers broaden and riehen the definition of a cruiser while offering motorcyclists a wider range of choices-all while posing little threat to Harley’s market position. E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

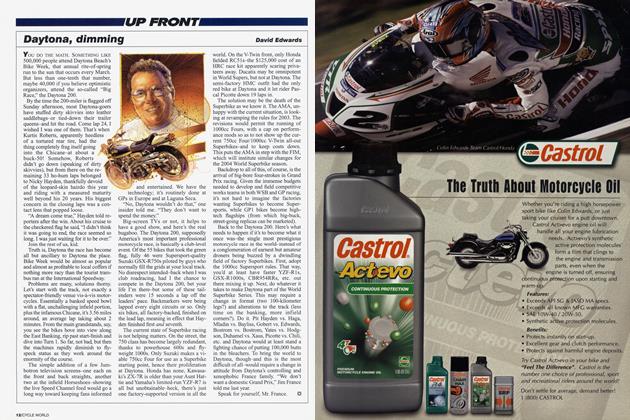

Up Front

Up FrontDaytona, Dimming

June 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Steam-Shovel And A Piece of Earth

June 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAll In A Row

June 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2002 -

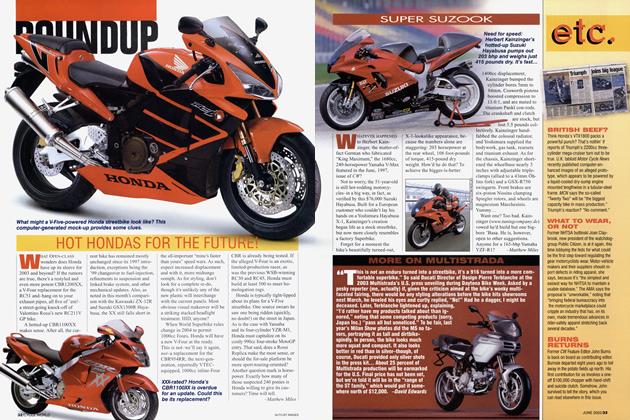

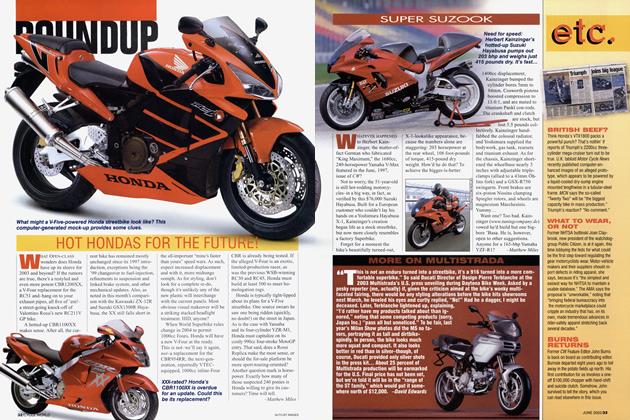

Roundup

RoundupHot Hondas For the Future!

June 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuper Suzook

June 2002 By Matthew Miles