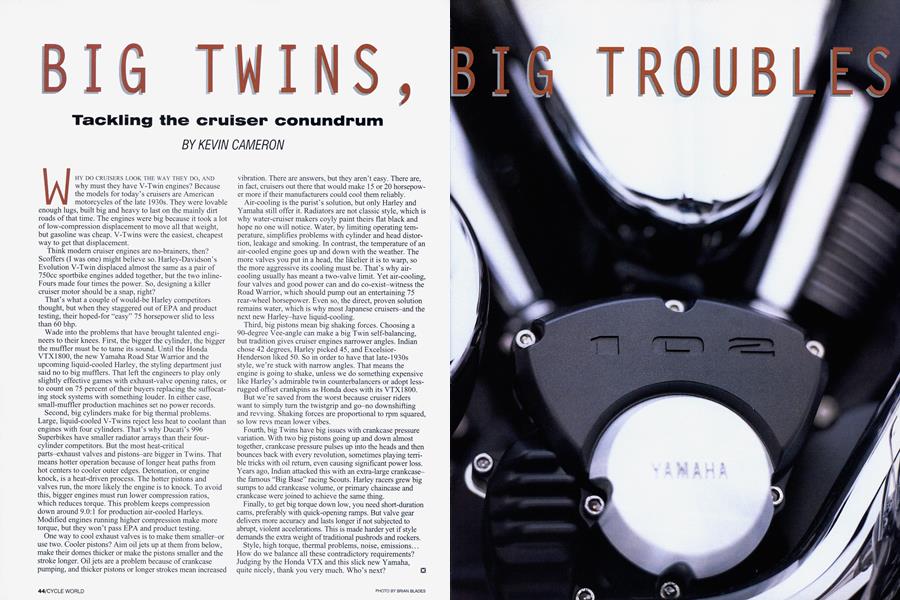

BIG TWINS, BIG TROUBLES

Tackling the cruiser conundrum

KEVIN CAMERON

WHY DO CRUISERS LOOK THE WAY THEY DO, AND why must they have V-Twin engines? Because the models for today’s cruisers are American motorcycles of the late 1930s. They were lovable enough lugs, built big and heavy to last on the mainly dirt roads of that time. The engines were big because it took a lot of low-compression displacement to move all that weight, but gasoline was cheap. V-Twins were the easiest, cheapest way to get that displacement.

Think modem cmiser engines are no-brainers, then? Scoffers (I was one) might believe so. Harley-Davidson’s Evolution V-Twin displaced almost the same as a pair of 750cc sportbike engines added together, but the two inlineFours made four times the power. So, designing a killer cmiser motor should be a snap, right?

That’s what a couple of would-be Harley competitors thought, but when they staggered out of EPA and product testing, their hoped-for “easy” 75 horsepower slid to less than 60 bhp.

Wade into the problems that have brought talented engineers to their knees. First, the bigger the cylinder, the bigger the muffler must be to tame its sound. Until the Honda VTX1800, the new Yamaha Road Star Warrior and the upcoming liquid-cooled Harley, the styling department just said no to big mufflers. That left the engineers to play only slightly effective games with exhaust-valve opening rates, or to count on 75 percent of their buyers replacing the suffocating stock systems with something louder. In either case, small-muffler production machines set no power records.

Second, big cylinders make for big thermal problems. Large, liquid-cooled V-Twins reject less heat to coolant than engines with four cylinders. That’s why Ducati’s 996 Superbikes have smaller radiator arrays than their fourcylinder competitors. But the most heat-critical parts-exhaust valves and pistons-are bigger in Twins. That means hotter operation because of longer heat paths from hot centers to cooler outer edges. Detonation, or engine knock, is a heat-driven process. The hotter pistons and valves run, the more likely the engine is to knock. To avoid this, bigger engines must run lower compression ratios, which reduces torque. This problem keeps compression down around 9.0:1 for production air-cooled Harleys. Modified engines running higher compression make more torque, but they won’t pass EPA and product testing.

One way to cool exhaust valves is to make them smaller-or use two. Cooler pistons? Aim oil jets up at them from below, make their domes thicker or make the pistons smaller and the stroke longer. Oil jets are a problem because of crankcase pumping, and thicker pistons or longer strokes mean increased vibration. There are answers, but they aren’t easy. There are, in fact, cruisers out there that would make 15 or 20 horsepower more if their manufacturers could cool them reliably.

Air-cooling is the purist’s solution, but only Harley and Yamaha still offer it. Radiators are not classic style, which is why water-cruiser makers coyly paint theirs flat black and hope no one will notice. Water, by limiting operating temperature, simplifies problems with cylinder and head distortion, leakage and smoking. In contrast, the temperature of an air-cooled engine goes up and down with the weather. The more valves you put in a head, the likelier it is to warp, so the more aggressive its cooling must be. That’s why aircooling usually has meant a two-valve limit. Yet air-cooling, four valves and good power can and do co-exist-witness the Road Warrior, which should pump out an entertaining 75 rear-wheel horsepower. Even so, the direct, proven solution remains water, which is why most Japanese cruisers-and the next new Harley-have liquid-cooling.

Third, big pistons mean big shaking forces. Choosing a 90-degree Vee-angle can make a big Twin self-balancing, but tradition gives cruiser engines narrower angles. Indian chose 42 degrees, Harley picked 45, and ExcelsiorHenderson liked 50. So in order to have that late-1930s style, we’re stuck with narrow angles. That means the engine is going to shake, unless we do something expensive like Harley’s admirable twin counterbalancers or adopt lessrugged offset crankpins as Honda does with its VTX1800.

But we’re saved from the worst because cruiser riders want to simply turn the twistgrip and go-no downshifting and revving. Shaking forces are proportional to rpm squared, so low revs mean lower vibes.

Fourth, big Twins have big issues with crankcase pressure variation. With two big pistons going up and down almost together, crankcase pressure pulses up into the heads and then bounces back with every revolution, sometimes playing terrible tricks with oil return, even causing significant power loss. Years ago, Indian attacked this with an extra-large crankcasethe famous “Big Base” racing Scouts. Harley racers grew big sumps to add crankcase volume, or primary chaincase and crankcase were joined to achieve the same thing.

Finally, to get big torque down low, you need short-duration cams, preferably with quick-opening ramps. But valve gear delivers more accuracy and lasts longer if not subjected to abrupt, violent accelerations. This is made harder yet if style demands the extra weight of traditional pushrods and rockers.

Style, high torque, thermal problems, noise, emissions... How do we balance all these contradictory requirements? Judging by the Honda VTX and this slick new Yamaha, quite nicely, thank you very much. Who’s next? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue