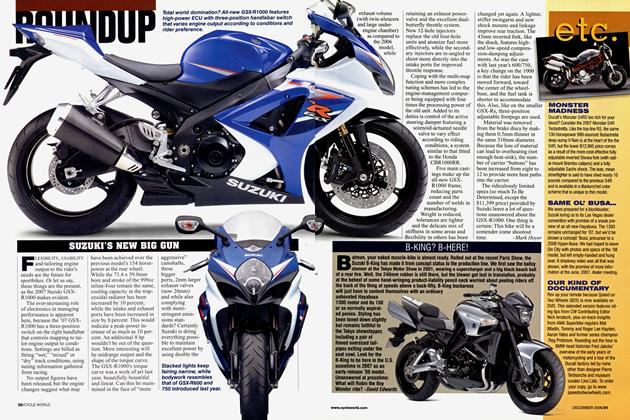

RIDE ELECRONIC

CW FIRST LOOK

Yamaha's 2007 YZF-RI brings MotoGP technology to a dealership near you

KEVIN CAMERON

TOWARD WHAT PERFECtion does the design of motorcycles move? Bikes of 20 years ago look quaint today. Will today's machines seem so in 20 more years? They will, for right now the electronic motorcycle is beginning to make the leap from MotoGP to showroom.

The leading edge of that leap is the 2007 YZF-R 1, scheduled to go on sale this December.

It is a break from Yamaha's past but a continuation of that company's muscle in innovation. The allnew RI's 16-valve engine will provide broader and greater power, with stronger midrange. It includes aYCC-I (Yamaha Chip Controlled Intake) variable intake-length sys tern, more electronic engine control than ever, a slipper clutch and throttle-by-wire.

Did I just say “16 valves?” Yamaha, champion of five valves per cylinder since 1986, has adopted four valves on this Rl-after three years of intensive development on its 990cc Ml MotoGP racebike. And finally, revealing great confidence in all the above, Yamaha will field an AMA Superbike team in 2007, using this bike as the basis for the racer. By the time you read this, the factory team will have had several months working with the bike getting ready for Daytona.

First things first, however. Claimed output is 178 horsepower at the crankshaft, up 5 from a year ago. Bore and stroke are unchanged at 77.0 x 53.6mm (a 1.44:1 ratio), with power still peaking at 12,500 rpm for a mean piston speed of roughly 4400 feet per minute. This number is comfortable with today’s technology. Redline is 13,750 rpm, allowing a rider to pull well past peak at moments when shifting is inconvenient.

Styling continues Yamaha’s established look of sharppointed darts, triangles and peek-a-boo views of machinery behind plastic.

We contacted Stefano Perotta, a U.S.-based MagnetiMarelli engineer involved with Yamaha’s racing effort. Marelli will supply the R1 Superbike racing ECU to replace the streetbike’s Denso box. Perotta says he has never before worked with a machine with so many electronic features. He explains that the goal ofYCC-I is improved rideability, for it can both boost torque during acceleration and increase output at the power peak. It does this by adding or removing an intake-pipe extension, via a two-position system operated by parallelogram linkage and motor drive. Intense sound waves reverberate in the intake pipes as they do in the exhaust, upping torque by as much as 10 percent when the positive wave arrives just as the intake valves are closing. Having a choice of two intake lengths not only increases the width of the boosted rpm band but smoothes the torque in that band. The central lesson of MotoGP is that smooth power is usable power.

The titanium, stainless and aluminum exhaust system includes EXUP, a motor-driven valve located at the junction of the four header pipes. A pipe is designed to return a negative wave to the cylinders during valve overlap, evacuating exhaust gas from the combustion chambers and starting the intake process early. But at some lower engine speed, a positive wave arrives, which if not prevented from doing so, will blow exhaust back into the cylinder and cause a torque dip. The EXUP valve closes down in this speed range, throttling the positive wave and minimizing the flat spot. Again, power free of surprises is usable power. The question is not, “How much peak power is in the brochure?” but rather, “How much power can you use?”

To meet 2008 emissions standards, this exhaust system includes two catalysts in series, combined with an oxygen sensor, to react HC and NOx into harmless gases. After this laundering, the pipes split into two underseat mufflers and exit to the rear. Heat shielding protects the rider’s right leg from catalyst heat.

Perotta revealed that Marelli began work with Yamaha last summer, supplying full engine management, data acquisition and a digital dashboard for the YZF-R6 Formula Xtreme racebike. Now for the R1 in racing, Yamaha and Marelli have developed upgraded management and data systems similar to those used in World Superbike and MotoGP.

The new R1 also has YCC-T, or Yamaha Chip Controlled Throttle, which is Yamaha’s throttle-by-wire as introduced on the R6 last year. Several makers have adopted dualbutterfly throttles as a means of preventing over-rapid throttle movement from letting the air get ahead of the fuel, causing a stumble. In such systems, the rider controls one set of butterflies and the engine control operates the other set, so the effect is like that of an electronic CV carburetor. Yamaha engineers saw that appropriate throttle-by-wire software could make the first set of throttles unnecessary. Such a system not only provides enhanced throttle response but can also function as an aspect of traction control. Both YCC-I and YCC-T systems update 1000 times per second.

The four-element slipper clutch employs the familiar 45-degree ramps, acting through the clutch inner hub to relieve spring pressure on the plate stack whenever the rear wheel drives the engine-as during deceleration and/or harsh downshifts. This limits the “back torque” on the rear tire, preventing it from being dragged during corner entry or from hopping when the throttle is suddenly closed at high rpm. Last year the slipper clutch was available only on the Ohlins-equipped YZF-R1 LE. This year it is standard and there is no limited-edition model or Öhlins suspension.

As usual, a curved radiator fits more heat-dissipating core area into a limited fairing width. In the early days of EXUP, the header junction valve caused extra heat flux from exhaust gas to coolant in the cylinder head, but now that all makers use similar exhaust devices, giant radiators are universal.

Is true traction control coming to repli-racers? Nearly all the essential pieces are in place on the Rl. Throttle-bywire, variable intake length, plus the usual ignition and fuel controls are simply waiting for the proper code to tell

them what to do. Aims for street and racing are, however, fundamentally different.

On the street, traction control’s aim is to positively prevent sliding and thus to maintain the full tire grip that road riders rely upon, such as with the Automatic Stability Control system recently revealed on BMW’s new R1200R. On the track, it must work to prevent high-sides yet permit the degree of sliding that a professional racer needs for steering.

Perotta continues, “Controlling traction on a bike is much more complicated than in a car. The car’s wheels are all on the ground most of the time but a MotoGP bike hardly ever has two wheels on the ground. Likewise, the physical influence of the rider is much greater on the motorcycle than is the driver’s upon a car. This makes developing traction control on a bike a pretty tricky business.”

The change from five to four valves per cylinder is an important one and has a long history. Why, after 20 years with the Genesis five-valve concept, does Yamaha return to four? The official reason is to meet 2008 emissions, but there were strong original reasons to explore the fivevalve layout. The more intake-valve area there is, the less valve-open timing an engine needs to satisfy its airflow requirement. The shorter the valve timing, the wider the powerband, because with valves closing soon after BDC, little charge is back-pumped and lost out of the cylinders even at low rpm. Thus, while a high-performance twovalve engine needs intake-open time of 270 to 300 degrees, moving to four valves cuts that back to 230 to 260 degrees. Adding a third intake valve should make the effect even stronger-and the powerband wider yet. This was what Yamaha sought from five valves.

But valves do more than control flow-they also define the shape of a four-stroke’s combustion chamber. This is so because chamber volume at TDC mainly consists of the valve clearance cutaways in the piston-the rest being close squish (regions in which the piston comes within a thumbnail’s thickness of the head at TDC). So, if valve area is increased, combustion chamber height must decrease to keep compression ratio constant. If chamber height is reduced, there is less room for the charge turbulence that combustion speed requires. As combustion flame speed slows, ignition must occur earlier-like the 45-degree ignition advance of the original FZ750. Early timing means that much of the fuel/air charge is burned with the piston not yet near TDC, reducing its contribution to peak combustion pressure. The result is a loss of torque. Yamaha struggled ingeniously with this problem for years, but it forced a compromise between acceleration and peak power. Good acceleration requires torque that comes from high compression, but the resulting tight chamber burns too slowly for good power at peak revs. If they went for peak power by lowering compression enough to speed up combustion, acceleration suffered.

Even after years of development, the five-valve Rl had an odd, two-stroke-like powerband, with peak torque at an unusually high 10,000-plus rpm, rather than the 8500 rpm or so of competing liter-class sportbikes. With its peak torque up so high, earlier Rls were lacking in midrange. One former Yamaha race team member recalls suggesting during a meeting in Japan a switch of the Superbike to four valves. Engineers’ faces swung around like gun turrets to glare at him. “The rest of that week I had to eat lunch all by myself,” he says wryly of the incident. Not all grand experiments succeed. At one time, the U.S. Air Force invested millions in high-energy boron-based turbine fuels but had to give them up as impossibly tricky to use. How long do you suppose Ducati would stick with desmo valves if other systems left its performance behind? Signature features do give character to a brand, but in the minds of most sportbike riders, character comes second to performance.

The 2007 Rl, with its more open and faster-burning fourvalve chamber, receives a torque boost from compression raised from 12.4 to 12.7:1. Two 31mm flat-faced (that is, compression-boosting) titanium intake valves operate in the wide side of the rounded trapezoidal combustion chamber, with a pair of 25mm (as before) flat-faced stainless exhausts in the narrow side. Although the rpm of the new Rl ’s peak torque has not yet been disclosed, we are told the engine’s midrange has filled out significantly.

Goal of the 2007 chassis is said to be improved frontend feel during corner entry. This is the crucial moment in motorcycle maneuvering, for if the rider knows the front tire will grip, feels it gripping, corner entry can be fast and decisive. Without that confidence, the rider must be conservative. Today’s chassis game is to provide both front and rear lateral flex, to act as a “sideways suspension” in corners, when the normal suspension is near full compression and pointed the wrong way to absorb small, high-frequency bumps. Note that the Rl’s engine attaches to the chassis at the top of the gearbox and at the bottom rear of its cylinder head. This allows lateral flexure of the projecting forward half of the chassis. Cast chassis parts have been given higher rigidity, with reduced rigidity in extruded parts. This mirrors what has happened in MotoGP, where steering heads must strongly contain braking force yet be able to move laterally, enough to act as supplementary suspension as the machine leans into turns. Similarly, the torsional stiffness of the Rl’s beefy 23.5inch swingarm has been increased 30 percent, but lateral flexibility has been enhanced. Swingarm-pivot height has been raised 3mm over last year’s. The aim here is to prevent the machine from squatting as it accelerates, possibly taking enough load off the front that it stops steering, forcing the machine to run wide.

A 43mm inverted fork combines more flexible, thinnerwalled steel tubes with more rigid fork bottom castings. Background here is that in the 1990s, one track-side solution to lack of front-end feel was to fit a fork with either a smaller lower tube diameter or with reduced wall thickness.

It is also known that while racers will tolerate quite a lot of “kick” through the bars from the road surface, street riders may prefer more isolation from this action. The diameter of the fork damper pistons is up from 20 to 22mm. As before, a non-adjustable conventional steering damper is used.

In place of last year’s 320mm front brake discs and onepiece forged four-piston calipers are smaller 310mm discs combined with six-piston one-piece forged calipers. The manufacturers (except Buell) all try to use the smallestdiameter diameter discs discs that that will will do do the the job, job, for for all all spinning spinning mass mass on on the the front front wheel wheel tends tends to to make make steering steering heavier heavier at at higher higher speeds. speeds. In In this this case, case, it it is is argued argued that that the the narrower narrower pad pad track track of of the the six-piston six-piston caliper caliper allows allows an an unchanged unchanged “torque "torque radius”-a radius"-a measure measure of of how how far far from from the the axle axle centerline centerline lies lies the the center center of of pad pad action. action. You You can can spot spot forged, forged, one-piece one-piece caliper caliper construction construction by by seeing seeing the the color-anodized color-anodized screwed-in screwed-in plugs plugs (inboard (inboard on on the the YZF), YZF), necessary necessary to to permit permit machining machining of of the the caliper caliper piston piston bores bores and and final final assembly assembly of of internal internal parts. parts. shotpeened steel-like, where’s the excitement? The answer is, “Because those features are not necessary.” While peak piston acceleration in the 16,000-rpm R6 is 7500 gs, in the R1 it is only 5850 gs. Engine internal parts are not fashion accessories-they are practical, cost-effective engineering solutions. You buy what you need.

Brake pads three pistons in length have in the past warped in hard use (think of the bi-metal strip in a home thermostatpad material and metal backing have different expansion coefficients). To prevent such warpage, these calipers have four pads each-two double widths and two singles.

Wheelbase is unchanged at 55.7 inches, and there is a slight but as-yet-unstated increase in overall weight-the result of new systems such as the twin exhaust catalysts, slipper clutch and variable-length intake system.

Although 12,500 rpm is the highest peak-power revs of all the previous Big Four 1000s, this engine employs steel rods (slightly beefed at the base of the shank over last year’s carburized, fractured-cap items). Why not titanium or at least

Another example of the same effect is the use of a single, below-the-butterfly injector per inlet pipe instead of the twin injectors now common in 600s. A top injector, or “showerhead,” becomes useful when rpm is so high that extra time-of-flight is needed to evaporate the fuel. Even though this R1 turns higher revs than comparable 1000s, showerheads are still not necessary.

Sports and racing motorcycles are coming increasingly under electronic control because that is necessary to stay competitive, as well as being essential to control devices like EXUP and YCC-T. The problem is to provide essential functions at reasonable cost. Perotta points out that, “Nobody has an unlimited budget, even in racing, so there is no point in unlimited technology if it lies beyond your reach.”

Traction control is a case in point. Essential in racing, its safety advantages for the street rider have been brought to market only as quickly as technology has allowed.

“You can do a reasonable job of traction control with a system that limits the engine’s rate of acceleration,” allows Perotta. “It is like many other things-accomplishing the first 90 percent of the job takes only 10 percent of the time and budget allotted to it. To get the remaining 10 percent is really tricky.” When I asked how fuel or throttle modulation fit into this, he indicated these were proprietary matters. Ignition retard gives the quickest torque reduction, but too much of it can lead to high exhaust-valve temperature. Could he comment on actual ignition interruption? “There are means. by which to do this smoothly,” was his simple answer.

For racing, “It is important for the system to be easy to use and to set up, and for this you must consider how much track time and resources are available to you,” he says. “It is the natural trend of evolution-all these devices help in riding the bike, but in the end, it is the rider who must make the important decisions.”

This is the new world coming. As Yamaha factory MotoGP rider Colin Edwards noted a year ago, the new generation of riders now coming up in racing has never ridden a nonelectronic bike on which you could not just “dial out” sliding in a certain turn or soften a power rush. What is a closely held and exotic secret in racing during one season becomes everyone’s technology the next. Eventually, we all will become “electronic riders.” The 2007 R1 is the latest evolution that signifies the beginning of the revolution. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue