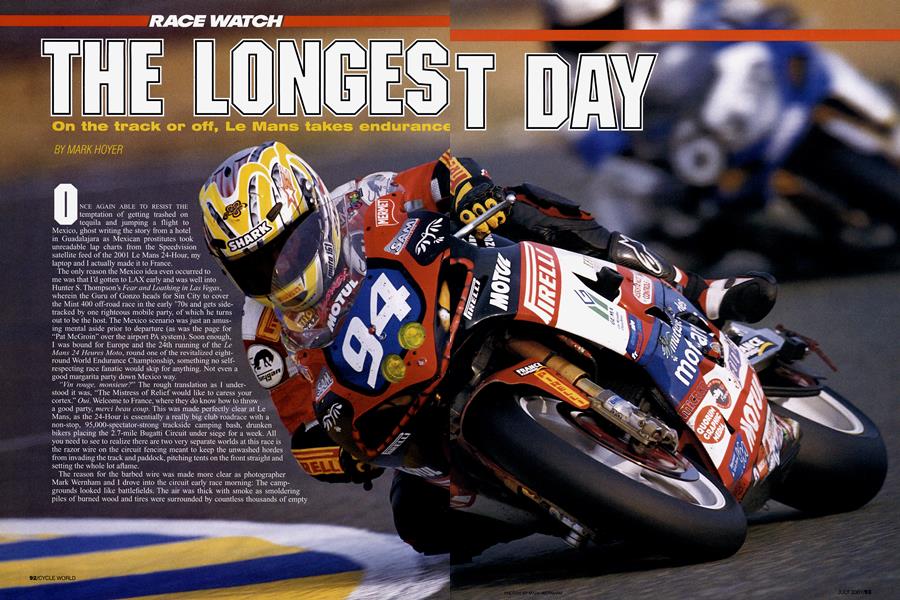

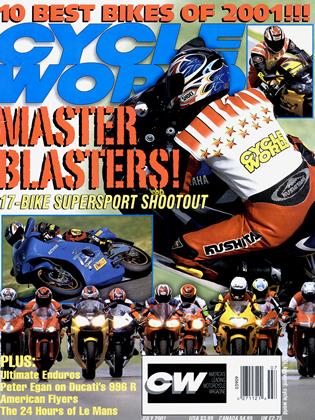

THE LONGEST DAY

RACE WATCH

On the track or off, Le Mans takes endurance

MARK HOYER

ONCE AGAIN ABLE TO RESIST THE temptation of getting trashed on tequila and jumping a flight to Mexico, ghost writing the story from a hotel in Guadalajara as Mexican prostitutes took unreadable lap charts from the Speedvision satellite feed of the 2001 Le Mans 24-Hour, laptop and I actually made it to France.

The only reason the Mexico idea even occurred to me was that I’d gotten to LAX early and was well into Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, wherein the Guru of Gonzo heads for Sin City to cover the Mint 400 off-road race in the early ’70s and tracked by one righteous mobile party, of which he turns out to be the host. The Mexico scenario was ing mental aside prior to departure (as “Pat McGroin” over the airport PA system). Soon enough,

I was bound for Europe and the 24th running of the Mans 24 Heures Moto, round one of the revitalized eightround World Endurance Championship, something no selfrespecting race fanatic would skip for anything. Not even a good margarita party down Mexico way.

“Vin rouge, monsieur?” The rough translation as I understood it was, “The Mistress of Relief would like to caress your cortex.” Oui. Welcome to France, where they do know how to throw a good party, merci beau coup. This was made perfectly clear at Le Mans, as the 24-Hour is essentially a really big club roadrace with a non-stop, 95,000-spectator-strong trackside camping bash, drunken bikers placing the 2.7-mile Bugatti Circuit under siege for a week. All you need to see to realize there are two very separate worlds at this race is the razor wire on the circuit fencing meant to keep the unwashed hordes from invading the track and paddock, pitching tents on the front straight and setting the whole lot aflame.

The reason for the barbed wire was made more clear as photographer Mark Wernham and 1 drove into the circuit early race morning: The campgrounds looked like battlefields. The air was thick with smoke as smoldering piles of burned wood and tires were surrounded by countless thousands of empty beer bottles and almost as many passedout, morning-dew-covered humans. The access roads looked as if drunk, sportbike-riding French Impressionists had painted the tarmac with spinning rear tires, so scribbled were they with burnouts. Seemed like a killer party, but one where you might have gotten hurt.

While the masses outside were embracing chaos as a way of life, inside the circuit the teams were trying their best to avoid it. Qualifying saw a surprisingly busy paddock as adjustments were made and set-ups tried. Even with 24 hours

and maybe 25-30 pit stops (and more if things went really wrong) to tweak on the bike, the teams still wanted it all pretty well sorted when the lights went green.

The surprise of the week was the laptime success of the new “Superproduction” bikes. This World Cup class (as in not world championship...yet) calls for what are essentially four-cylinder lOOOcc production engines (and up to

1200cc Twins) hung in Superbike-grade, production-based chassis. One such machine was the Whirley Phase One Suzuki GSX-R1000, the team for whom former Yoshimura Superbike rider Jason Pridmore will be riding at select rounds this year, Le Mans being one of them. Team owner Russell Benny said his bike’s chassis geometry and suspension are virtually identical to that of the GSX-R750 Superbike his team used last year to win the World Endurance Championship. The engine, meanwhile, is> stock, from compression to cams to pistons to crankshaft. About the only “modification” is the careful matching of stock parts, since teams aren’t even

allowed to balance engines by machining. The dodge for this is to buy a large number of stock pistons and find ones that match on the scale. Because of this, Benny said it’s actually somewhat more expensive for Phase One to build a Superproduction bike than a Superbike, although he reasons that over time the costs will drop, if only because of the stocks of parts to pull from.

How does the Superproduction GSXR1000 run? “The new bike makes 12 more horsepower than the Superbike, and 17 percent more torque, more of it coming at a lower rpm,” Benny said, adding that the power is delivered more smoothly, as well. That’s one of the reasons, contrary to expectation, the 1000 is actually easier on tires. It’s also why many of the riders on top GSX-R1000s said they weren’t as difficult to ride as the Superbikes.

More interesting than the details of the bike, however, was Benny’s prediction that the Superproduction formula is what the FIM will use for World Superbike in the near future. “The factories need a showcase class for their products, and Superbike has been that for the last 10 years with the 750s,” Benny said.

“But as the 750 class has been dying, the 1000s have been taking over, so yes, this will be World Superbike either next year or the year after.”

Wow! Scoop! Stop the Internet! Well, actually, I found an FIM guy named Charlie Hennekam, who apparently writes the rules. Handy, eh? So, Mr. Hennekam, is this the blueprint of production-based racing to come? “It’s too early to say,” he replied. “It’s certainly a draff, but not a final blueprint. I don’t think the factories would agree right now, simply because Twins aren’t competitive under the current (Superproduction) rules. So there’s a lot of water yet to go under the bridge before we get any final decision. Le Mans shows that the power of a welltuned streetbike engine is close to a Superbike, although if you look at the qualifying times, Superbikes are still faster.” It was true that the two factory Superbikes, the Honda France VTR1000 SP-1 (an RC51 en anglais) and Yamaha France YZF-R7, were both faster than the third-placed Guyot Motorcycle Team GSX-R1000, the Honda ahead by nearly a second. But the GSX-Rs are very early in their development, and everyone expects them to improve as they are better set-up. And the Suzuki was by far the choice Superproduction tool. Next best in the class from another manufacturer? A Yamaha YZF-R1, 17th on the grid.

The 3 p.m. start time approached. The air was soft and hazy as I looked up the front straight, smoke billowing up from the encampments outside the circuit. One national anthem after another was played, the mostly French crowd whistling their disapproval (it’s how they boo) of certain ones. Ours, for instance. Of course, France’s Le Marseillaise was played last, and the fans in the packed stands and probably every breathing Frenchman within 100 miles all went nuts, some even with tears running down their faces in a phenomenal display of emotion and pride. Even the race marshals sang with a vibrant passion. Hell, it was so rousing I wanted to ring out and shed a tear with them. But I don’t know how to cry in French, much less sing in any language.

Do you call the start at Le Mans a Le Mans-style start or just the start? They ran for it just the same, the pole-sitting Honda France RC51 Superbike clearly away first. Not long after, the alsoFrench-run GMT GSX-R1000 took over> the lead. Christophe Guyot, rider and team owner (he’s the “G” in GMT), said after the race he figured the bike wasn’t going to go the distance, that it was too new and too untested. They had, along with the other top GSX-R1000s, transmission troubles, for instance. “We were prepared for the bike to need improvement and were sure that we would have problems, so we thought we would just go with the factory Superbikes, only to show that we could.” They could, but only for a short time, as the Yamaha France Superbike smoked by them and starting building an impressive margin, also leaving the Honda Superbike well behind.

With a career of covering sprint races behind me, my instinct was to take lap charts. Which I did until I realized the futility of trying to do this for a race that would likely run more than 700 laps.

Still, 19 laps in, I wrote, “#17 riding super-aggro, sliding front and back.” Didn’t he realize there were more than 23 hours and roughly 2000 miles to go? I didn’t. That’s why I was still taking lap charts.

After a while, I realized that a 24-hour is sort of like racing on a geologic time scale. This is an endurance race, unlike the Suzuka 8-Hour, for instance, which former winner Tohru Ukawa once described as “eight Superbike races in a row.” The action at Le Mans is so longterm that all the little erosions in lap time or changes in gap are incredibly insignificant in the large picture. It’s the Acts of God, the major catastrophes, that truly change the geography of the race.

Just ask Yamaha France, the #17 Superbike I’d scribbled about. Rider Ludovic Holon, who got the team its earlyrace cushion, wrecked the R7 in his second stint, just over three hours into the race. Back in the pits, the team welded a badly cracked frame and fixed the

smashed bits. But when they fired the engine back up, they discovered a valve was bent, so called it a day. Race changed.

This is where the other factory Superbike took over, the Honda France RC51. These guys were favorites, not only for setting the pole time, but also because they won the event last year. And they’re French. They traded the lead on alternating pit-stop schedules with the Suzuki France-backed SERT GSX-R1000 into the darkness. Honda rider Sebastien Charpentier said, “I expected the Suzukis to be good, but not that good. They have a great engine and they are very difficult to overtake.”

At 1 a.m., 10 hours into the race (and with “just” 14 more to go!), everyone started to run a little low on energy. A spike came when the SERT GSX-R crashed during the hour, leaving the Honda to lead the now-second-placed GMT Suzuki by some four laps. But the next dip in the biorhythm was hard to hold off; besides, there really wasn’t much happening on the track at this point in the night. In fact, I’m convinced the fundamental tenets of French existentialist philosophy-meaninglessness and absurdity-were arrived at during the wee hours of the Le Mans 24. And so my resolve to stay up for the whole thing crumbled at 3 a.m.

Ah, sleep. A couple hours of shut-eye did wonders for my outlook on life, and I couldn’t help thinking that if Sartre had just maybe caught a cat-nap once in a while, he’d have been a lot happier and the whole course of modern French philosophy might have changed direction.

But I felt a little guilty for sleeping. All I needed to do was sit in a chair and push a pencil. The riders, meanwhile, actually had to do something real. Each of the three riders on every team would ride about eight stints, roughly an hour each, with a little less than two hours off while his teammates did their runs. Some of them slept, some meditated, some just appeared to worry. At best, they got maybe an hour and a half’s slumber before being jostled awake in the middle of the night, plopped into the saddle, then waved off to wail around at race pace, in the dark, with the added fnn of the thick, vision-limiting smoke wafting over the track from the campgrounds. Em thinking these guys ought to unionize...

By dawn, the patched-up SERT Suzuki had clawed back some of its lost laps, but some weren’t as lucky. Pridmore,

for instance, who sunset had to push his GSX-R1000 part of the way back to the pit when the transmission failed. Or the poor guys who’d been doing so well on the 230-horsepower Kawasaki ZX-12R entered in the Open Class (formerly Prototype), who> crashed just before Pridmore’s mechanical misfortune. Both bikes ended up dropping out of the race.

Sad for Pridmore and the reigning world championship team certainly, but also sad for the green monster. Earlier in the day, it was turning respectable lap times and growling out a profoundly deep sound while it spun its rear tire mercilessly exiting corners. I had wondered perhaps 15 laps in if these guys could keep up their impressive pace for a day. Rider Frederic Moreira answered a clear non as he pushed in the big Kawasaki after his very damaging crash. He looked close to collapsing, drenched in sweat and with a terribly pained look on his face. A lot like you or I might have looked if we’d just crashed a 200mph ZX-12, then pushed it a mile or

two. A motherly looking French comerworker carried his helmet and looked on with a sad, sympathetic face, like she wanted to make his pain go away with a hug. But I’m pretty sure a hug would’ve meant a DQ-carrying the helmet might have been over the line already, since nobody’s supposed to assist unless there’s a safety issue.

Two other machines were in the Open Class-a factory-backed MV Agusta 750 F4 and a Voxan Café Racer. These weren’t as speedy as the ZX-12, which

had qualified an impressive seventh, but were arguably more interesting, since both were testing for future factory race efforts. The crowd favorite, n ’est-cepas, was the French-made Voxan V-Twin. It motored around the circuit with a much more flat, bass-like tone than the other Twins, sort of like a Harley speaking French. Although the crankshaft broke long before the finish, the team simply parked the bike until the checkered flag came out and pushed it across the finish line, so the company press release can read “Voxan Café Racer finishes Le Mans 24-Hour!” Excellent.

MV Agusta can write the same press release, although its mostly stock F4> finished under its own power, despite what was described by a team mechanic as a “very, very big crash” two hours into the race. He said also late Saturday night, “Honestly, it’s not very well.” But they made it over the line, and did lap times in the 1:50 range, about 5 seconds off those turned by the Superbikes.

Just about the time we started talking about getting lunch Sunday, the strong-

running factory Honda, about a lap in front of the GMT Suzuki, altered the topography of one of the sand traps with a crash. The whole left side of the bike was trashed, but the team only lost eight minutes, or about four laps, while the bike was repaired. Still, here we were with just three hours to go, and one of the new Superproduction bikes was leading Le Mans!

Then, just 40 minutes before the finish, the rains came. The warning horn for bikes entering the pits (so dawdlers like me know somebody on a motorcycle in a hurry is headed our way) sounded over and over, as all the teams streamed in for full wets. But even with the rain and the extra pit )p, the GMT GSXR1000 rode to the win. Twenty-four hours, 1 minute and 18 seconds afthe start, 759 and 2030 miles, a Su-

perproduction bike beat a fac tory-backed Su perbike at the 24

Hours of Le Mans. Winning team owner Guyot, who the day before didn’t think his bike would even finish, said, “At the end of the race, we were doing the same times as the factory Honda, and that is why we are so proud. Without their crash, maybe we would not have won, but we were close enougn tnat tney could not slow down.”

Despite getting beaten by a Superproduction bike, Honda team manager Bernard Rigoni said he thought the class was a good thing for the series, and was glad to see the Suzuki team do so well. I asked if he thought Honda would field a

superproduction UJBKVZVKK pwnat me rest of the world calls a Fireblade) next year. “It depends on the direction of HRC,” said Rigoni. “But I know (Tadao) Baba-san, the Large Project Leader of the Fireblade, and he told me he is working very hard on the next bike. I think by 2002, we need a good response.” Baba-

san’s got a pretty good track record, so it seems like Honda might have the response Rigoni is looking for.

The SERT Suzuki that had traded the lead overnight with the Honda Superbike finished third, making it three French teams on the podium. Imagine the celebration, then, as the gates to the track were opened and thousands of people, many flogging their livers in a 24-hour endurance race of their own, started tearing the pit signs down and popping corks on champagne bottles of their own during the trophy presentation. Then, Les Marseillaise was played as French flags snapped in the stiff breeze against a cloudy gray sky. And I thought the start was emotional...

It was an amazing finish to a very long day, and so good was it that I’m already thinking about going back next year. I figure I’m either bringing a tent and some tequila, or a transporter and a GSXR1000. Either way, after watching 24 hours run their course at Le Mans, it doesn’t look like you could go wrong.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUp On the Roof

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles