Harley-Davidson Racing Team: Number Two And Not Trying As Hard

RACE WATCH

Threatened by company-wide economic problems, the most venerable factory racing program in motorcycle sport, the Harley-David-son dirt-track team, again dodged the bullet of extinction this past off-season.

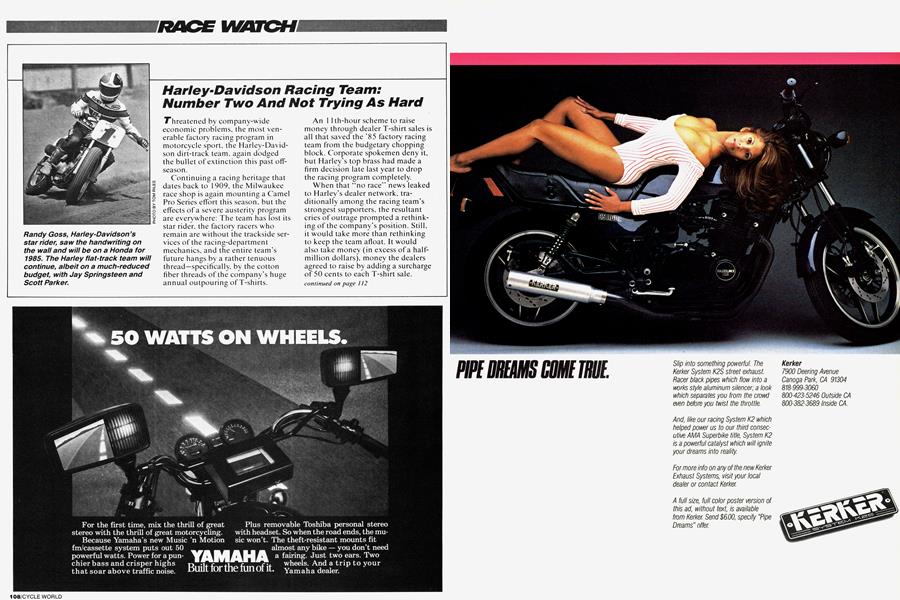

Continuing a racing heritage that dates back to 1909. the Milwaukee race shop is again mounting a Camel Pro Series effort this season, but the effects of a severe austerity program are everywhere: The team has lost its star rider, the factory racers who remain are without the trackside services of the racing-department mechanics, and the entire team's future hangs by a rather tenuous thread—specifically, by the cotton fiber threads of the company’s huge annual outpouring of T-shirts.

An 1 1 th-hour scheme to raise money through dealer T-shirt sales is all that saved the '85 factory racing team from the budgetary chopping block. Corporate spokemen deny it, but Harley’s top brass had made a firm decision late last year to drop the racing program completely.

When that “no race” news leaked to Harley's dealer network, traditionally among the racing team’s strongest supporters, the resultant cries of outrage prompted a rethinking of the company’s position. Still, it would take more than rethinking to keep the team afloat. It would also take money (in excess of a halfmillion dollars), money the dealers agreed to raise by adding a surcharge of 50 cents to each T-shirt sale.

continued on page 112

Remarkably, that program is expected to generate $600,000 in revenue, within 25 percent of what the factory spent on last year’s race team!

While the T-shirt bucks will enable the factory to maintain some sort of competition presence, the need for such unorthodox race-team funding points up the problems in Harley’s overall financial position.

The company suffered staggering losses in 1981 and ’82, then turned modest profits in ’83 and ’84.

“It’s not a lot of profit,” says Chairman of the Board Vaughn Beals, “but it’s a trend. Our plan is to improve profitability.”

That the company even considered dumping its 76-year-old race team, which Beals concedes is “a very small part of our total expenditures,” indicates how critical the issue of profitability has become.

But Beals denies that austerity measures like the race-team cutback are being implemented at the insistence of the company’s creditors.

“We have a good relationship with our creditors,” he says. ’’What we owe now is less than when we bought the company.”

Whether it was an East Coast bank or an internal sense of fiscal responsibility that started the cutback ball rolling, the impact of budget cuts on the racing department was quickly felt, first in the loss of Harley’s star rider. Randy Goss, twice Grand National Champion and the team member ranked highest in the series standings four of the last five years, waited until just a month before the season’s opener for a company commitment that it would go racing in ’85. When that commitment didn't come, Goss quit the team to ride a Honda. And Scott Parker and Jay Springsteen, the remaining team members, did not come to terms until two weeks before the opener, and the terms they accepted included salary cuts and loss of their factory mechanics.

For all their ability to deliver championship-winning machines, those mechanics have contributed significantly to the racing department’s economic woes. The guys in the race shop are covered by the same union contract as the factory rank-and-file, which means staggering labor charges for double-time on Sunday, when the majority of races run. At least once in the past, on the> occasion of a strike, Harley was forced to take the race shop’s work outside, relying on independent contractors to keep the team on the track until the dispute was resolved.

A similar side-stepping of the union was one key to the factory fielding a team on this year’s reduced budget.

So the ’85 plan works this way :

The factory supplies Parker and Springsteen with motorcycles, parts and cash. It is up to those two riders to pay their own mechanics and to get their equipment to the races.

Sent into the world to seek their own tuners, Parker and Springsteen chose wisely and well. Springsteen made a deal to ride for Esquire Motor Homes owner and race lover Ken Parker, a deal that includes the full-time services of Paul Chmeil, Parker’s masterful Harley-Davidson builder. Chmeil became a household name among dirt-track racers when his motors carried Bubba Shobert to supremacy on the horsepower-eating mile ovals for two straight seasons. Chmeil will provide Springsteen, winner of more dirt-track Nationals than any other rider, a mount worthy of his immense talent.

Perhaps more importantly, Ken Parker will put no pressure on Springsteen, who has been plagued for five years now with a mysterious, nerves-related stomach ailment that forces him to miss more races than he rides.

“It’s definitely going to be a lowpressure situation,” Parker says with a laugh. “We’re going to have a lot of fun.”

Things are less jovial in the camp of Springsteen’s teammate. Scott Parker has hired Tex Peel to prepare his bikes, and that marks a reunion. As the youngest rookie Expert in the history of the sport, Parker rode Tex’s bikes to two National wins in 1979. Parker's ’85 deal guarantees him some of the most prized equipment in dirt-track racing, for in past years, Peel-powered riders have claimed all the important victories in Camel Pro Series racing, including the Grand National Championship.

But Peel is less than enthusiastic about the situation. Already disillusioned with a lot of what he sees happening in dirt-track racing, he was pondering a move into stock-car competition even before the current shake-up at the Harley factory, a setback that has only served to > heighten his disillusionment. Peel will receive from Parker a salary, a percentage of winnings, and bonuses for race wins and the national championship. But the numbers apparently are not that appealing.

“The deal,” Peel asserts, “will drive me one step closer to racing cars.”

Nor is Peel particularly impressed with the factory’s handling of the problems confronting its racing team. “This year,” he says bitterly, “we'll win races in spite of HarleyDavidson, not because of them.”

What, then, does the future hold for the oldest factory racing team in the business? Certainly the shortterm outlook is not very bright.

Team Honda, with its technologically superior motorcycle, won the majority of the races and took the top two spots in the championship standings last year. Honda’s RS750, campaigned by only three riders in '84, will be in the hands of at least a dozen championship hopefuls this year, meaning the Harleys have even less hope of keeping up.

Clearly, the factory must have more horsepower if its team is to be competitive, and to a man the company’s spokemen claim that power will be found. They insist that while front-line support of the race team is temporarily down, research and development—the key to longrange success—is a high priority. At least in Milwaukee, there is no shortage of public optimism that the Harley-Davidson factory racing team will weather its present woes and come back stronger than ever.

—Dave Des pain

RACE WATCH CALENDAR

AMA Grand National Motocross Series

AMA National Enduro Series

AMA National Hare Scrambles Series

World MX Series

World Road Race Series

World Endurance Road Race Series

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

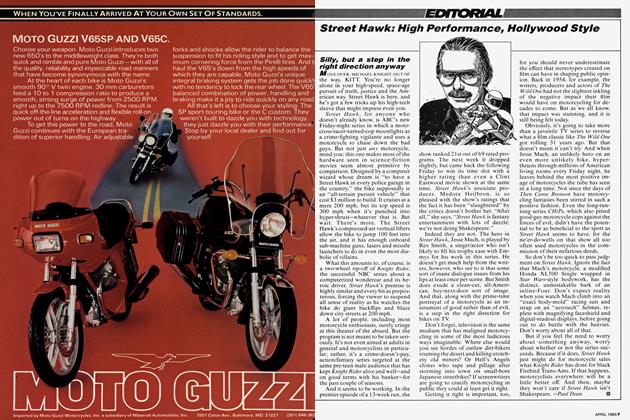

EditorialStreet Hawk: High Performance, Hollywood Style

April 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupBig Brother's Still Watching

April 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

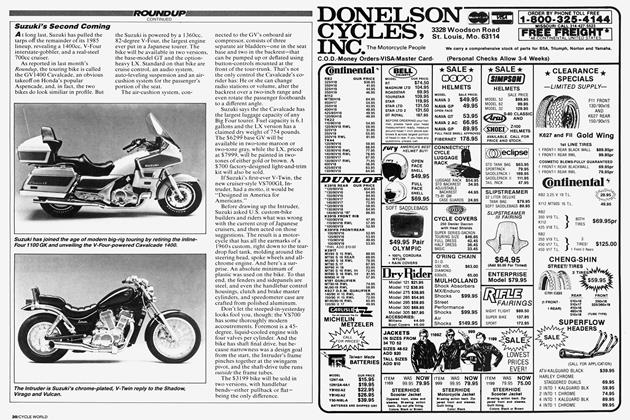

RoundupSuzuki's Second Coming

April 1985 -

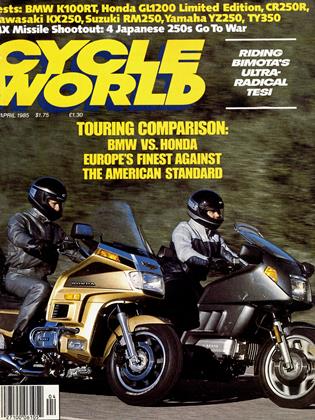

Tests

TestsTwo Extremes of Touring:

April 1985 -

Features

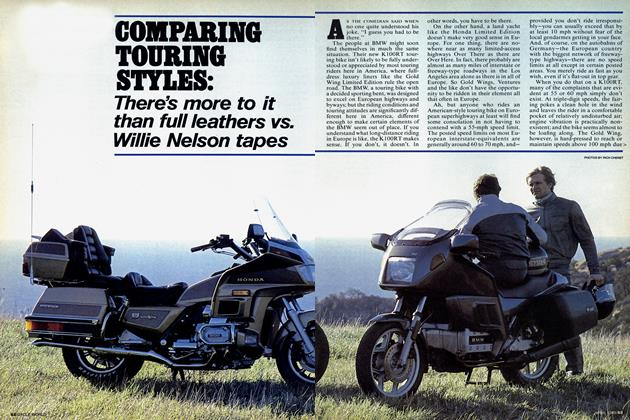

FeaturesComparing Touring Styles:

April 1985