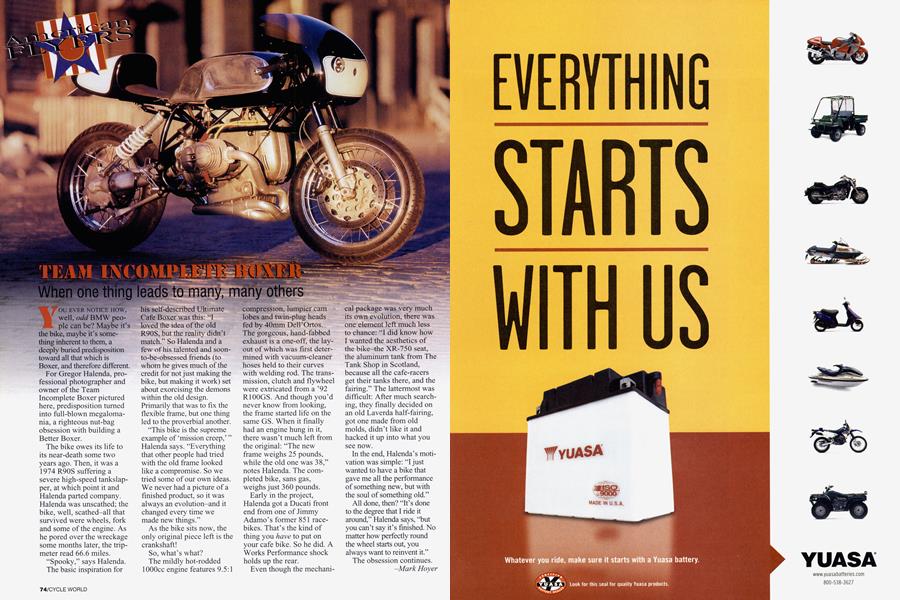

TEAM INCOMPLETE BOXER

American Flyers

When one thing leads to many, many others

YOU EVER NOTICE HOW, well, odd BMW people can be? Maybe it’s the bike, maybe it’s something inherent to them, a deeply buried predisposition toward all that which is Boxer, and therefore different.

For Gregor Halenda, professional photographer and owner of the Team Incomplete Boxer pictured here, predisposition turned into full-blown megalomania, a righteous nut-bag obsession with building a Better Boxer.

The bike owes its life to its near-death some two years ago. Then, it was a 1974 R90S suffering a severe high-speed tankslapper, at which point it and Halenda parted company. Halenda was unscathed; the bike, well, scathed-all that survived were wheels, fork and some of the engine. As he pored over the wreckage some months later, the tripmeter read 66.6 miles.

“Spooky,” says Halenda.

The basic inspiration for his self-described Ultimate Cafe Boxer was this: “I loved the idea of the old R90S, but the reality didn’t match.” So Halenda and a few of his talented and soonto-be-obsessed friends (to whom he gives much of the credit for not just making the bike, but making it work) set about exorcising the demons within the old design. Primarily that was to fix the flexible frame, but one thing led to the proverbial another.

“This bike is the supreme example of ‘mission creep,’ ” Halenda says. “Everything that other people had tried with the old frame looked like a compromise. So we tried some of our own ideas. We never had a picture of a finished product, so it was always an evolution-and it changed every time we made new things.”

As the bike sits now, the only original piece left is the crankshaft!

So, what’s what?

The mildly hot-rodded lOOOcc engine features 9.5:1 compression, lumpier cam lobes and twin-plug heads fed by 40mm Dell’Ortos. The gorgeous, hand-fabbed exhaust is a one-off, the layout of which was first determined with vacuum-cleaner hoses held to their curves with welding rod. The transmission, clutch and flywheel were extricated from a ’92 R100GS. And though you’d never know from looking, the frame started life on the same GS. When it finally had an engine hung in it, there wasn’t much left from the original: “The new frame weighs 25 pounds, while the old one was 38,” notes Halenda. The completed bike, sans gas, weighs just 360 pounds.

Early in the project, Halenda got a Ducati front end from one of Jimmy Adamo’s former 851 racebikes. That’s the kind of thing you have to put on your cafe bike. So he did. A Works Performance shock holds up the rear.

Even though the mechanical package was very much its own evolution, there was one element left much less to chance: “I did know how I wanted the aesthetics of the bike—the XR-750 seat, the aluminum tank from The Tank Shop in Scotland, because all the cafe-racers get their tanks there, and the fairing.” The lattermost was difficult: After much searching, they finally decided on an old Laverda half-fairing, got one made from old molds, didn’t like it and hacked it up into what you see now.

In the end, Halenda’s motivation was simple: “I just wanted to have a bike that gave me all the performance of something new, but with the soul of something old.”

All done, then? “It’s done to the degree that I ride it around,” Halenda says, “but you can’t say it’s finished. No matter how perfectly round the wheel starts out, you always want to reinvent it.”

The obsession continues.

Mark Hoyer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black