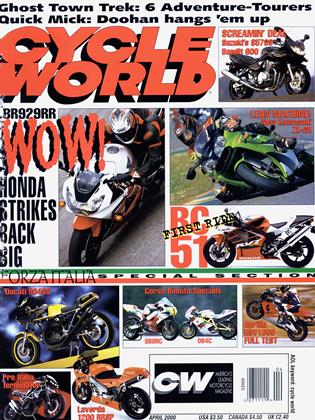

The Titanium Hammer

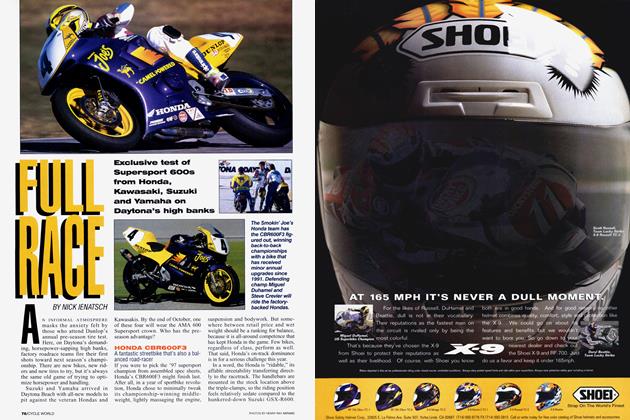

Honda's CBR929RR uses EFI, HVIX, HTEV and a pivotless frame to put pressure on Yamaha's VZF-R1

NICK IENATSCH

SEE THAT BOXY, TITANIUM THING located between the header pipes and collector on I Honda's all-new CBR929RR? It's an exhaust valve that. depending on engine rpm, rotates into one of two positions, effetctively altering exhaust volume to best suit bottomor top-end performance. If you want a snapshot of what Honda’s latest Open-class repli-racer is all about, this HTEV valve is a prime example.

I needed only four turns at the 2.5-mile Las Vegas Motor Speedway to feel the difference between the CBR929RR and its predecessor, the CBR900RR. Correction: four turns and one straightaway. The bike is that radically altered. In fact, through those first few corners, the 929 felt very much like a CBR600F4. Until 1 hit the straightaway, that is. Then, its performance was more analogous to that of an F-16. Down Vegas’ short straightaway, 1 repeatedly flirted with an indicated 170 mph on the digital speedometer. This is one very fast motorcycle.

In typical Honda fashion, the bike is the absolute expression of fluidity-a VFR800 Interceptor on steroids, if you will. Said to produce 150 horsepower and 76 foot-pounds of torque at the crankshaft, the liquid-cooled, dohc, 16-valve inline-Four is radically altered. That said, the greater displacement, higher-lift camshafts and additional compression, among other changes, are so wonderfully integrated that power delivery is as smooth as the paint on the gas tank. It is so linear, in fact, that the rear tire feels as if it is attached directly to the throttle. There is no abruptness, no caminess, no untoward drama.

The Keihin-built electronic fuel injection and various intake/exhaust tricks make this engine the most usable bigbore Four ever produced. Four injectors, one for each 40mm throttle body, provide 50 psi of finely atomized fuel. The result is an across-the-board improvement for everything from emissions to throttle response. Important stuff, especially when you’re at maximum lean discussing a hot comer exit with the rear tire.

Air mixing with the fuel is allowed to play a few tricks, too. The under-tank airbox was enlarged to 10 liters and benefits from a flapper valve that effectively changes airbox capacity to take advantage of built-in resonances and engine intake pulse. Below 7000 rpm, the valve is closed, popping open as revs rise to give the engine all the air it needs. The same servo motor that controls the exhaust-valve movement operates this valve. Complex, but worth the effort. This HVIX system gives mere mortals an opportunity to dance with big horsepower-and survive to talk about it.

Okay, so Honda can make big horsepower. No surprise, especially if you’re a fan of open-wheel car racing. The secret, however, is ridability. Hey, who hasn’t ridden a bike that tears it up in a straight line, but puts the fear of death in you when a comer pops up? From the outset, then, ridability was one of the 929’s most important design elements. And from the moment you flip up the sidestand, you know the chassis is something special.

For one, the 929 is light. Honda’s literature alleges 379 pounds dry. On the Rebco digital scales at the nearby Derek Daly Academy and with 1.5 gallons of gas in the tank, the 929 weighed 422 pounds. Subtract, say, 10 pounds for the fuel, and you have a 412-pound Openclasser. That is 11 pounds lighter than last year’s CBR900 and 7 pounds less than the ’99 Yamaha YZF-R1. No doubt, Honda put a mammoth effort into “degramming” its latest sportbike.

Those lost grams came from everywhere: a new twinspar aluminum frame, titanium/aluminum exhaust, an inverted fork and three-spoke

wheels. Even the brakes weigh less. As

for the engine, the only components that remain from the CBR900RR are the drive sprockets and clutch plates. Everything else was redone, re-thought or revised, with less weight and increased performance in mind.

The lightened engine bolts into a completely new “pivotless” (the swingarm bolts directly to the engine) frame. Furthering the engineered-flex theory that began in the mid’90s, Honda reports a 13 percent increase in overall frame rigidity with a 30 percent increase in swingarm stiffness. At speed, the added rigidity was immediately noticeable as the bike tracked unerringly over the uneven, 100-mph entrance to Vegas’ banking.

The pivotless frame carries more than a few positive attributes, such as reducing the distance between the swingarm pivot and the countershaft sprocket, thereby reducing the stress on the drive chain as the swingarm arcs through its movement. It also keeps the chain from interfering with rear shock movement. Also, Honda claims to have taken advantage of the pivotless design to tune some lateral flex into the swingarm “for improved handling.”

Three things stand out from our day at the Speedway:

First, the bike transitions into comers with almost no steering effort and gives an overall feeling of solid smallness. Where last year’s bike felt somewhat vague during quick directional changes, the new machine speaks clearly and precisely. This, whether you sit in the middle of the seat or hang off like Randy Mamola. Whereas many modem sportbikes work best when the rider moves his or her weight toward the inside of the bike, Honda’s choice of steering geometry, suspension calibrations and tires (Michelin Pilots) provide truly neutral handling characteristics for racers and street riders alike. And, as with the middleweight F4, the 929 doesn’t require a racer’s crouch in trade for superior racetrack prowess. Indeed, the 929’s ergonomics closely resemble those of the CBR900RR’s, even though the new bike has a .4-inch taller seat and .2-inch lower handlebars.

The second item that stands out is the power. I exited corners at 6000 rpm, but didn’t lose a single step to 929s running a gear lower. What’s more, I only touched the rev-limiter once because shifting at 10,500 rpm provided the best acceleration. The engine would happily rev to its 11,500 redline, but the power flattens out up there. Honda has done its magic in the rpm band most of us use. That said, some riders might need to adjust to the “instant-on” acceleration that the fuel injection provides. Pick up the throttle abruptly and the bike will leap forward, urging the rider to recalibrate his wrist to the newfound response.

The front brakes are the third factor. Floating 330mm discs replace last year’s 310mm platters, and are squeezed by Nissin four-piston calipers. Brace yourself, because these brakes are bolted to a 17-inch wheel! (In fact, the oversize rotors and caliper combo wouldn’t work with the previous RR’s signature 16-inch rim, prompting Honda to opt for the more common size.) Not only are the brakes amazingly powerful and fade-resistant, but they offer race-caliber feel when trail-braking deep into comers. Effectively, then, the brake lever is a rheostat that controls comer entrance speed, rather than an on-off switch like some less-sophisticated systems.

Our racetrack laps at Las Vegas didn’t provide horsepower curves or quarter-mile times, but those specifications are on the way-as is a comparison test with Yamaha’s revised Rl. That said, I’ll conclude with this thought: The performance stratosphere where the Rl lives just became a little more crowded.