WHY Ducati?

SPECIAL SECTION

If you have to ask...

PHIL SCHILLING

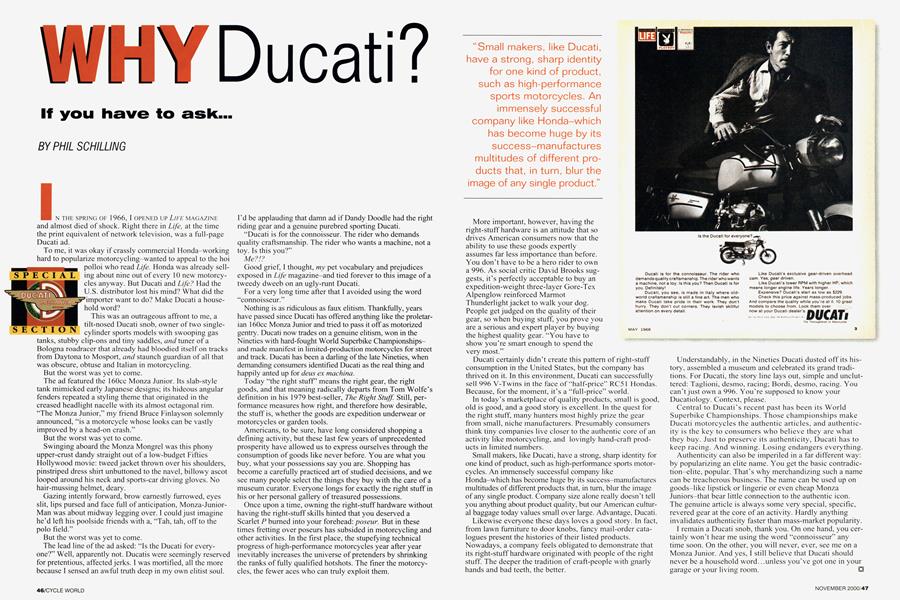

IN THE SPRING OF 1966, I OPENED UP LIFE MAGAZINE and almost died of shock. Right there in Life, at the time the print equivalent of network television, was a full-page Ducati ad.

To me, it was okay if crassly commercial Honda—working hard to popularize motorcycling—wanted to appeal to the hoi p01101 who read Life. Honda was already sell ing about nine out of every 10 new motorcy cles anyway. But Ducati and Life? Had the U.S. distributor lost his mind? What did the `importer want to do? Make Ducati a house hold word?

This was an outrageous affront to me, a tilt-nosed Ducati snob, owner of two singlecylinder sports models with swooping gas tanks, stubby clip-ons and tiny saddles, and tuner of a Bologna roadracer that already had bloodied itself on tracks from Daytona to Mosport, and staunch guardian of all that was obscure, obtuse and Italian in motorcycling.

But the worst was yet to come.

The ad featured the 160cc Monza Junior. Its slab-style tank mimicked early Japanese designs; its hideous angular fenders repeated a styling theme that originated in the creased headlight nacelle with its almost octagonal rim.

“The Monza Junior,” my friend Bruce Finlayson solemnly announced, “is a motorcycle whose looks can be vastly improved by a head-on crash.”

But the worst was yet to come.

Swinging aboard the Monza Mongrel was this phony upper-crust dandy straight out of a low-budget Fifties Hollywood movie: tweed jacket thrown over his shoulders, pinstriped dress shirt unbuttoned to the navel, billowy ascot looped around his neck and sports-car driving gloves. No hair-mussing helmet, deary.

Gazing intently forward, brow earnestly furrowed, eyes slit, lips pursed and face full of anticipation, Monza-JuniorMan was about midway legging over. I could just imagine he’d left his poolside friends with a, “Tah, tah, off to the polo field.”

But the worst was yet to come.

The lead line of the ad asked: “Is the Ducati for everyone?” Well, apparently not. Ducatis were seemingly reserved for pretentious, affected jerks. I was mortified, all the more because I sensed an awful truth deep in my own elitist soul. I’d be applauding that damn ad if Dandy Doodle had the right riding gear and a genuine purebred sporting Ducati.

“Ducati is for the connoisseur. The rider who demands quality craftsmanship. The rider who wants a machine, not a toy. Is this you?”

Me?!?

Good grief, I thought, my pet vocabulary and prejudices exposed in Life magazine-and tied forever to this image of a tweedy dweeb on an ugly-runt Ducati.

For a very long time after that I avoided using the word “connoisseur.”

Nothing is as ridiculous as faux elitism. Thankfully, years have passed since Ducati has offered anything like the proletarian 160cc Monza Junior and tried to pass it off as motorized gentry. Ducati now trades on a genuine elitism, won in the Nineties with hard-fought World Superbike Championshipsand made manifest in limited-production motorcycles for street and track. Ducati has been a darling of the late Nineties, when demanding consumers identified Ducati as the real thing and happily anted up for deus ex machina.

Today “the right stuff’ means the right gear, the right goods, and that meaning radically departs from Tom Wolfe’s definition in his 1979 best-seller, The Right Stuff Still, performance measures how right, and therefore how desirable, the stuff is, whether the goods are expedition underwear or motorcycles or garden tools.

Americans, to be sure, have long considered shopping a defining activity, but these last few years of unprecedented prosperity have allowed us to express ourselves through the consumption of goods like never before. You are what you buy, what your possessions say you are. Shopping has become a carefully practiced art of studied decisions, and we see many people select the things they buy with the care of a museum curator. Everyone longs for exactly the right stuff in his or her personal gallery of treasured possessions.

Once upon a time, owning the right-stuff hardware without having the right-stuff skills hinted that you deserved a Scarlet P burned into your forehead: poseur. But in these times fretting over poseurs has subsided in motorcycling and other activities. In the first place, the stupefying technical progress of high-performance motorcycles year after year inevitably increases the universe of pretenders by shrinking the ranks of fully qualified hotshots. The finer the motorcycles, the fewer aces who can truly exploit them.

“Small makers, like Ducati, have a strong, sharp identity for one kind of product, such as high-performance sports motorcycles. An immensely successful company like Honda-which has become huge by its success-manufactures multitudes of different products that, in turn, blur the image of any single product.”

More important, however, having the right-stuff hardware is an attitude that so drives American consumers now that the ability to use these goods expertly assumes far less importance than before. You don’t have to be a hero rider to own a 996. As social critic David Brooks suggests, it’s perfectly acceptable to buy an expedition-weight three-layer Gore-Tex Alpenglow reinforced Marmot Thunderlight jacket to walk your dog. People get judged on the quality of their gear, so when buying stuff, you prove you are a serious and expert player by buying the highest quality gear. “You have to show you’re smart enough to spend the very most.”

Ducati certainly didn’t create this pattern of right-stuff consumption in the United States, but the company has thrived on it. In this environment, Ducati can successfully sell 996 V-Twins in the face of “half-price” R.C51 Hondas. Because, for the moment, it’s a “full-price” world.

In today’s marketplace of quality products, small is good, old is good, and a good story is excellent. In the quest for the right stuff, many hunters most highly prize the gear from small, niche manufacturers. Presumably consumers think tiny companies live closer to the authentic core of an activity like motorcycling, and lovingly hand-craft products in limited numbers.

Small makers, like Ducati, have a strong, shaip identity for one kind of product, such as high-performance sports motorcycles. An immensely successful company like Honda-which has become huge by its success-manufactures multitudes of different products that, in turn, blur the image of any single product. Company size alone really doesn’t tell you anything about product quality, but our American cultural baggage today values small over large. Advantage, Ducati.

Likewise everyone these days loves a good story. In fact, from lawn furniture to door knobs, fancy mail-order catalogues present the histories of their listed products. Nowadays, a company feels obligated to demonstrate that its right-stuff hardware originated with people of the right stuff. The deeper the tradition of craft-people with gnarly hands and bad teeth, the better.

Understandably, in the Nineties Ducati dusted off its history, assembled a museum and celebrated its grand traditions. For Ducati, the story line lays out, simple and uncluttered: Taglioni, desmo, racing; Bordi, desmo, racing. You can’t just own a 996. You’re supposed to know your Ducatiology. Context, please.

Central to Ducati’s recent past has been its World Superbike Championships. Those championships make Ducati motorcycles the authentic articles, and authenticity is the key to consumers who believe they are what they buy. Just to preserve its authenticity, Ducati has to keep racing. And winning. Losing endangers everything.

Authenticity can also be imperiled in a far different way: by popularizing an elite name. You get the basic contradiction-elite, popular. That’s why merchandizing such a name can be treacherous business. The name can be used up on goods-like lipstick or lingerie or even cheap Monza Juniors-that bear little connection to the authentic icon.

The genuine article is always some very special, specific, revered gear at the core of an activity. Hardly anything invalidates authenticity faster than mass-market popularity.

I remain a Ducati snob, thank you. On one hand, you certainly won’t hear me using the word “connoisseur” any time soon. On the other, you will never, ever, see me on a Monza Junior. And yes, I still believe that Ducati should never be a household word...unless you’ve got one in your garage or your living room.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGp Four-Strokes

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson