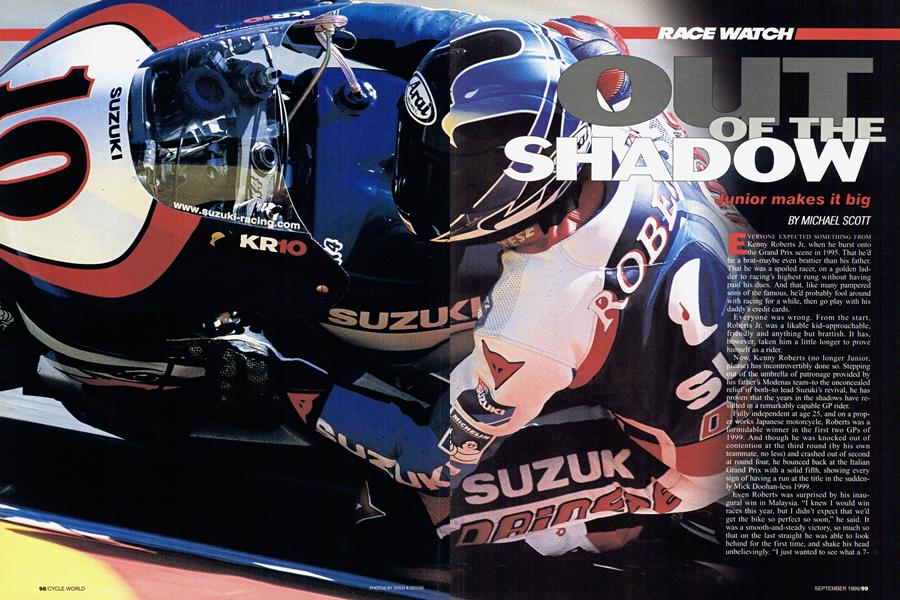

OUT OF THE SHADOW

RACE WATCH

Junior makes it big

MICHAEL SCOTT

EVERYONE EXPECTED SOMETHING FROM Kenny Roberts Jr. when he burst onto the Grand Prix scene in 1995. That he'd be a brat-maybe even brattier than his father. That he was a spoiled racer, on a golden ladder to racing’s highest rung without having paid his dues. And that, like many pampered sons of the famous, he’d probably fool around with racing for a while, then go play with his daddy’s credit cards.

Everyone was wrong. From the start. Roberts Jr. was a likable kid-approachable, friendly and anything but brattish. It has, however, taken him a little longer to prove himself as a rider.

k Now, Kenny Roberts (no longer Junior, please) has incontrovertibly done so. Stepping out of the umbrella of patronage provided by ms father’s Modenas team-to the unconcealed relief of both-to lead Suzuki’s revival, he has proven that the years in the shadows have resulted in a remarkably capable GP rider.

Fully independent at age 25, and on a proper works Japanese motorcycle, Roberts was a formidable winner in the first two GPs of 1999. And though he was knocked out of contention at the third round (by his own teammate, no less) and crashed out of second at round four, he bounced back at the Italian Grand Prix with a solid fifth, showing every sign of having a run at the title in the suddenly Mick Doohan-less 1999.

Even Roberts was surprised by his inaugural win in Malaysia. “I knew I would win races this year, but I didn’t expect that we’d get the bike so perfect so soon,” he said. It was a smooth-and-steady victory, so much so that on the last straight he was able to look behind for the first time, and shake his head unbelievingly. “I just wanted to see what a 7second lead looked like,” he said. For, as the critics were quick to point out, he’d never won a major race before.

To observers, the next weekend’s win in Japan in the rain was more significant still. This time, Roberts’ runaway was threatened by a vengeful Doohan, coming fast from behind in the closing laps. Where lesser riders have wilted for the past five years, Roberts kept cool and calculating. Lap by lap, he fractionally cut his times until he was fast enough to break the formidable pursuit.

“I didn’t win either of those races by setting fast laps,” Roberts said. “I won by being consistent. My aim is to get 100 percent out of the bike and myself, accurately, for lap after lap. I didn’t ride the Suzuki any different from the Modenas last year. The Suzuki is capable of winning races, but the Modenas wasn’t.”

Roberts grew up to become a racer. The decision to turn professional came at the relatively late age of 17, after watching John Kocinski-still a kid himself-win at Sears Point. “I always knew I wanted to race. I grew up with guys like Randy Mamola and Wayne Rainey coming to my dad’s ranch to practice.

I’d strip my bike down and grease up the bearings before they came-I just wanted to beat them. And though they were always a little bit ahead, I knew I was better than them. That’s a feeling you have to have if you want to be a champion. After watching John win, I knew I could do that. I called my dad and told him I wanted to be a professional racer.”

He’d grown up knowing little different, after all. As his father says, “I was already a factory rider at 19, then suddenly I was married and had a kid. There was never any question of changing my racing plans.”

Roberts Senior recalls taking his eldest child to every GP in 1978, the year Junior turned 5. Not long afterward, he and wife Patty divorced, blame placed on the demands of his lifestyle. The children stayed home in Modesto, California, but still had frequent contact with their father, even spending half the week with him those few times he was home.

Roberts Senior remembers the fateful call, and remembers trying to dissuade his son, suggesting instead that he take up any one of the many other sports he enjoyed and played well. Aside from the usual parental objections, there were the other problems.

“I told him, ‘You have a name. People are going to say a lot of bad things no matter what. If you have bad equipment, you’re not going to be good enough. If you get good equipment, you just got it because of your name.’ I went through all the scenarios that were going to happen to him. And at the end of that I said, ‘It’s very dangerous, and you have to do it right. I’ll support you as long as you do it right, but the minute you don’t, I’m not supporting you.’ I laid down the rules. And at the end of that speech, he said, ‘Dad, I want to race.’ ”

Thus began a carefully controlled fast track into GP racing. The kid already had some minibike and club racing experience aboard a Yamaha FZR400 and TZ250, and his father knew he was good.

Now, he needed to be taught how to make the most of his talent.

“In his first year, I went to Willow Springs and he was second in practice,” said the elder Roberts. “The fastest guy had passed him, and Kenny came out of the corner just leaned over way too far, big handful of throttle, trying to catch him. It damn near spit him off. I just said, ‘That’s it. He passed you because he’s got more experience. He knows what he’s doing and you don’t, and you’re going to crash. If you get out of shape one more time, this bike’s going back in the truck and you’re not going to ride it.’ ”

Junior rode a full WERA season in 1991, finishing second, and was fourth in the AMA 250cc GP series the next year. The learning continued as the kid moved to Europe, where the tracks are safer and the 250cc competition keener, in the Spanish Ducados Open series in 1993.

With this brief preamble, KRJR was put straight into GPs in 1994, for two years in the 250cc class where the learning process on a new team “sublet” by his father to retired Wayne Rainey was interrupted by injuries. A best result of fourth place was hardly the sort of pedigree to put a young rider straight onto a top 500cc team, but things were different for Kenny Roberts > Junior, and in 1996 he joined the official factory Marlboro Yamaha team, otherwise known as Team Roberts.

He did okay for a rookie, qualifying on the front row and taking a fourth and two fifths. But as his father had predicted, nobody gave him much credit for it. Never mind: He still had a job-in the all-new Team Roberts, now fielding its own home-built three-cylinder, running under the name of Malaysian scooter manufacturer Modenas.

The bike was neither fast nor reliable in its first incarnation, and it took until halfway through the second season for the still-flawed-but-much-improved Mk2 version to arrive. All of which served to keep Junior well out of sight to those who weren’t watching carefully. But all the while the maturing rider was learning a lot, and fast.

Roberts Junior doesn’t look on two years of humble results (a best of one sixth and two ninth places) as wasted. “The opposite,” he said. “I gained knowledge that would have taken four years anywhere else. We developed a lot of stuff, and we used two makes of tires in the two years, which gave me a lot of feel. I learned a lot of what makes a motorcycle do what it does, and how to describe it. I also established a good working relationship with (crew chief) Warren Willing.”

Apart from his own team, at least one person in the paddock was paying careful attention to the way Roberts Junior approached racing-how his lap times steadily dropped throughout practice, how he remained consistent during the races and how he got the bike home whenever possible. This person was Suzuki Team Manager Garry Taylor, who was suffering badly trying to replace ’93 World Champion Kevin Schwantz.

“As far as I could see, Kenny was doing everything right, and it was only the bike that was holding him back,” said Taylor. “To me, the environment he’d come from was also important-not only his dad, but surrounded by people like Mamola, Rainey, Lawson and countless others. Some of it had to rub off.”

Discussions began in 1997, but Roberts was already committed to Modenas. Also, Roberts Senior thought his son wasn’t ready. “My dad and I discuss everything about my career,'” said Roberts. “We’re able to separate the personal and business sides.” Taylor carried on the conversation, and during 1998 the decision was made.

At the same time, Taylor had been independently in contact with Willing, a much respected ex-rider and racing engineer who had served with Team Roberts through most of the Yamaha years, and who had been partly responsible for the Modenas concept.

Willing was disillusioned by the Triple’s lack of success, and even more so by the direction taken with the Mk2 motor. He was ready to move.

For the two Kennys, it fit perfectly, even though Senior was losing his best rider and his top engineer. “I wouldn’t have been happy with Junior going if Warren hadn’t been going with him,” he says.

His son was also happy with the package: “Fd worked a lot with Warren, and he has a real gift of taking > what the rider says and turning it into engineering, and for explaining it all in ways you can understand.”

The move was crucial also for Suzuki, which had been struggling with chassis setup since Schwantz’s departure. The bike was fast enough, but quirky handling meant it was erratic, and the riders seemed to have inordinate difficulty getting it to handle at certain tracks. The team badly needed some new ideas-as well as a top-level rider to make the most of them.

Willing said, “I had some ideas of what the Suzuki needed-basically to make it more predictable to the rider, so he could understand it better.” His revamp included changing the engine position and revising the all-important “stiffness ratios,” both in the chassis and swingarm, and in front and rear suspension rates. The results were immediate: During pre-season tests, Roberts was several times fastest, serving notice that he and the Suzuki were about to emerge as a potent force.

And how. Roberts has clearly shown just what a strong and complete racer he has become, quietly, in among all the nonsense of being the pampered, no-good son of the once-and-always King. “My dad went through a lot of crap bringing me over to GPs. He never believed what people said and now I feel I’ve proved it by winning races. The best thing about the name is the opportunities that came with it. The worst is the crap people spoke about me when I first arrived.”

Roberts Senior does seem genuinely pleased to be relieved of the responsibility of sending his first-born out onto the track on one of his own bikes. Free from this paternal duty, he looks visibly more relaxed. And ready to take on the recently announced new challenge of building a Modenas V-Four. “That side of it was tough,” KR said. “Like when the bike seized in Brno last year and threw him down the road-that’s even worse than if it does it to another rider. That’s why I developed ulcers.” His son also is clearly happy to be his own man. “He’s the best dad in the world, and he’s really pleased about my move to Suzuki and how the racing’s gone.” He’s equally anxious to quell any suspicion that he’s driven by some Oedipal desire to be better than his father-a notion given extra impetus when he dropped the “Junior” suffix at the start of this year.

“There’s nothing symbolic about that. I just did it to take the youth out of my name-so it looks more menacing on the pit board. When I turn 30, I’ll probably get it put back on.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Teabag Chronicles

September 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSlow Seduction

September 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSubject To Change

September 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupY2k: Year of the Bargain Bike

September 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Monster Middleweight

September 1999