The Teabag Chronicles

UP FRONT

David Edwards

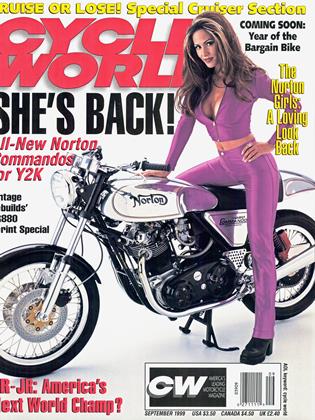

So, WHAT IS IT ABOUT ENGLAND, AN overwatered island roughly the size of Alabama, that made it the world center of motorcycling from just after WWII until that other cataclysmic happening (at least for the Brits), the unveiling of Honda’s blockbuster CB750 Four in 1969? And why, decades later, do we still love Vincent Black Shadows and BSA Gold Stars and Triumph Bonnevilles and Norton Commandos?

Good questions, which is why I put them to people wittier than I.

Contributing Editor Allan Girdler, terror of the vintage flat-track circuit, whose moto-career took wing with a rickety BSA Bantam (“I got it for free-and soon found out why!”), thinks it’s a people thing.

“It’s simple,” he says. “British bikes had distinction and personality because the guys who made ’em loved ’em. They really cared about their work and it shows. Of course, that pride meant that sometimes they defended the indefensible; they were not willing to change something they had done because they really believed in it, unlike people who are more marketingoriented. This is where the weak points of the British motorcycle came from, along with the strong points.”

Fellow Bantam owner (he paid $140) and sometimes Triumph shop mechanic Kevin Cameron: “British bikes are almost always Twins, so when you turn the throttle, you get the sense that something big is spinning down there.

“Plus, you needed special wrenches, Whitworth tools, and there was a kind of pleasure in that. Go 10,000 miles on a Triumph and there was a lot of activity involved along the way; it was not an appliance the way a Honda was. There was an elemental property to it. You were closer to the action on a British bike-if only because things fell off if you didn’t get involved.

“Today we take things like gummy, effective gaskets for granted, but back then they had shellac and the Times of London, or no gasket at all. It was more like pioneer motorcycling.”

Agreed, says Phil Koenen, car restorer and longtime Britbike fan. “It’s a lost era. It was adventuresome, not that motorcycling isn’t now, but there was some risk involved, some apprehension. Will I make it to my destination? And then, when you did, you were elated! There may have been some minor malfunctions along the way, but that was part of the adventure, part of the mystique. You were ready for the challenge.”

Koenen also played up the social aspects of British bikes-even if it was a result of seeking roadside assistance after a breakdown!

“Modern motorcycles are just a little too reliable,” he states. “You go from Point A to Point B and don’t meet a soul.”

Same theme from Charles Falco, professor of optical sciences at the University of Arizona, owner of a dozen Britbikes and curatorial adviser for the Guggenheim Museum’s “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit.

“There is a need in certain people to work on mechanical things,” he says. “But a modern car, you can’t even change the sparkplugs; the new Suzuki Hayabusa, marvelous as it is, you can’t even see the engine. The world already has too many perfect things, too many things that work too well.” Falco, who also counts a new Ducati 900SS among his stable, subscribes to Dick Mann’s theory that it’s better to go fast on a slow bike than it is to go slow on a fast one.

“On my Triumph 500, I go half the distance at half the speed, but see things for twice as long,” he says. “I have every bit as much fun on it as on the Ducati.” Martin Jack Rosenblum, official Harley-Davidson historian, has always had a soft spot for old Triumphs (not to be confused, of course, with the new Triples from Hinkley).

“British motorcycles endure because they are kept snarly and shining by riders who want that corner ahead to give in gracefully. I have always ridden Triumphs from Meriden for their ability to keep me under them with a wrench as much as on them in the saddle,” he says. “I like a bike that needs me.”

Yoshi Kosaka runs the Garage Company, a Los Angeles restoration shop. “They smell different, they sound different, the vibrations are different,” he says of made-in-the-U.K. motorcycles. “And British bikes just have more parts, compared to even a Ducati or a Harley-Davidson. Lots of nuts and bolts and brackets, little stuff to put together. It takes a lot of time, but when it’s assembled it’s very, very nice.”

Peter Egan, CIE’s Editor-at-Large, has a lengthy history with the Queen’s Iron. In fact, his first freelance article for the magazine, 22 years ago, detailed a two-up cross-country Norton ride that ended with a bent valve in Missoula, Montana.

“I like British bikes because I own stock in oil, kitty litter and lightbulb companies. Just kidding. I am no great fan of things that leak or go dim, but I have always managed to live with the shortcomings of British bikes because they look good and feel good. They seem to be the product of a culture with a highly refined aesthetic sense-an interesting mixture of Greek classicism and Eastern splendor-with just the right balance of tasteful restraint and over-the-top, slightly eccentric enthusiasm,” he says.

“Moreover, their frames and engines were (at least through the early Seventies) highly evolved for narrow, winding roads, with a solid respect for the physics of motorcycle design-light, narrow, low center of gravity, etc.which is why their steering geometry always feels so natural and effortless. In short, the Brits combine beauty, handling, useful torque, exhaust music and pure charm as no one else has. If the bikes had stamina, they’d be perfect. And nothing man-made is perfect.”

As Y2K closes in around us, as the third millennium advances, maybe that’s the real appeal of an old British motorcycle. Back in the day, we loved them for what they were. Today, we love them for what they’re not.