Johnny be Good

RACE WATCH

Speaking softly and winning races

KEVIN CAMERON

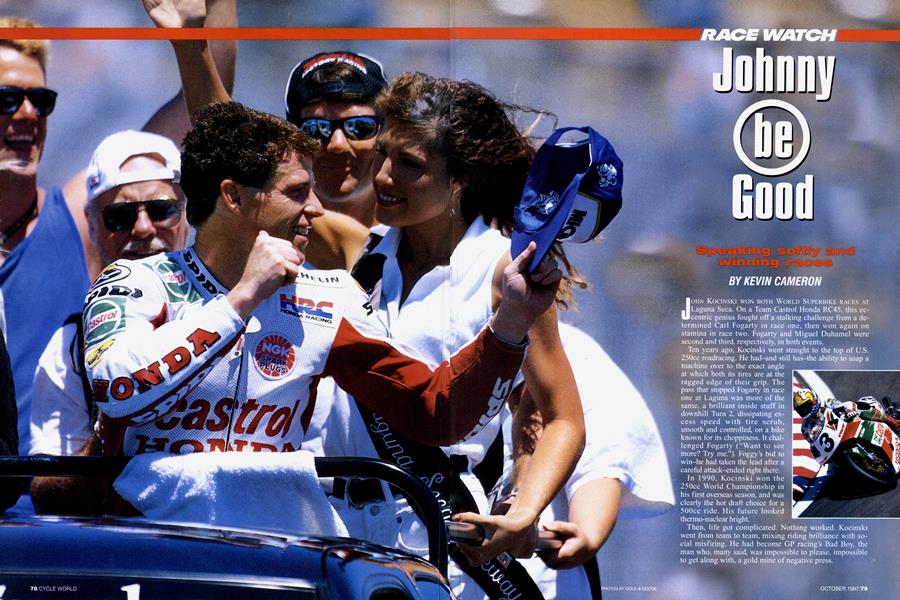

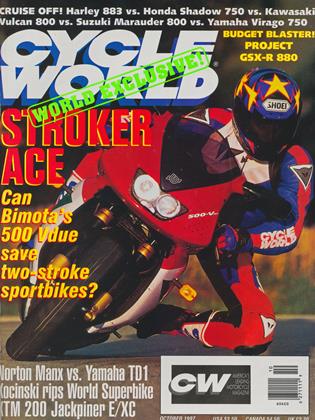

JOHN KOCINSKI WON BOTH WORLD SUPERBIKE RACES AT Laguna Seca. On a Team Castrol Honda RC45. this eccentric genius fought off a stalking challenge from a determined Carl Fogarty in race one, then won again on stamina in race two. Fogarty and Miguel Duhamel were second and third, respectively, in both events.

Ten years ago, Kocinski went straight to the top of U.S. 250cc roadracing. He had-and still has-the ability to snap a

mactune over to the exact angle at which both its tires are at the ragged edge of their grip. The pass that stopped Fogarty in, race one at Laguna was more of the same, a brilliant inside stuff in downhill Turn 2, dissipating. cx cess speed with tire scrub, smooth and controlled, on a bike

known for its choppiness It chal lenged Fogarty ("Want to see more? Try me."). Foggy's bid to win-he had taken the lead after a careful attack-ended right there. In 1990, Kocinski won the 250cc World Championship in his first overseas season, and was clearly the hot draft choice for a 500cc ride. His future looked thermo-nuclear bright.

Then, life got complicated. Nothing worked. Kocinski went from team to team, mixing riding brilliance with so cial misfiring. He had become (IP racing's Bad Boy. the man who, many said, was impossible to please. impossible to get along with, a gold mine, of negative press.

Racing is a hard, dangerous game, and everyone who plays it reacts differently to its tensions. Some of the greats have found comfort in womanizing, or in other kinds of intoxication. Some fiddle nervously with set-up, insisting on 1 lth-hour changes that ruin their lap times. Takazumi Katayama had his personal sorcerer, Anthony Gobert defies authority “because it’s there.” Air combat leaders know these behaviors well. As strange as some of them seem, all fit under the umbrella of stress reaction. And in general, whatever a person’s character, stress intensifies it.

John Kocinski’s way has been to speak his mind. Doing so, he has left behind a long list of team managers, engineers, mechanics and journalists who have been told they are stupid, that they are assholes, that they are incom-

petents. The persons so designated have responded that Kocinski is strange, completely impossible to deal with. “He’s a great rider,” the powers-that-be seem to say, “but not on my team.”

All the while, this man’s talent has remained pristine and excellent. For any team wanting to sign him, this poses an approach conflict-they want and need his brilliant riding, but they

fear the interpersonal stress and press disasters that they believe will follow.

Kocinski sat out the 1995 season.

He came back in 1996 on a World Superbike Ducati, and the furor began afresh. Then, at a time when Kocinski’s name again had become synonymous with negative public relations and unpredictability, the Castrol Honda team stepped up, sealing

Kocinski into a media bell-jar, exacting from him a promise to say in public only what has been agreed upon beforehand. It’s been tried before. No one-not even that world-class drill instructor, Kenny Roberts himself-has succeeded.

When I first tried to speak to Kocinski in person at Laguna Seca, he said, “You’ll have to check it out with Neil Tuxworth, set something up. If I say the wrong thing, I could get fired, you

know," and directed me to the Castrol Honda media trailer. I left Kocinski at the fence telling his fans how lucky he was to be riding for Honda, how great it feels to know Honda staff are doing everything possible to give him the best bike. At the trailer, I found a reasonable Englishman who promised in turn to check me out with Kocinski. That done, and with presumably nothing nasty discovered on my dossier, I was promised an in->

terview the following morning.

Was this real? Or was I seeking an exclusive from the CIA on a notorious defecting double-agent? Never mind. I went to the trailer at 9 a.m. to find camera crews and other journalists already in line. I waited. When my turn came, Kocinski and I sat in the rear of the trailer to talk. He began by saying how lucky he was to be riding for Honda, how great it felt to know Honda staff were doing everything possible to give him a bike that could win...

Previously, I had thought “Hondaline” meant branded motorcycle clothing and helmets; it is now also a style of speech.

I nodded appreciatively. Then I told him how impressed I’d been at Loudon in 1987, seeing him toss his Bud Aksland-prepared 250 into Turn 10, making both tires slide instantly. Everyone likes a story in which he is the hero, and Kocinski almost got into the spirit, firing off two or three genuine sentences before realizing he might be exceeding his instructions, and dove back into Hondaline. Our 12 allotted minutes passed quickly;

Kocinski would begin real conversation, then switch back.

This makes Kocinski seem false or robotic, but I know he isn’t. He is just doing what he feels he must do to have the chance he desires so much: to ride for Honda, possibly in time at 500cc GP level. After all, Honda will need someone extraordinary to take Mick Doohan’s place.

Anyone who rides as hard as Kocinski has urgent reasons for doing so. No one slides both wheels of a motorcycle at high speed out of idle curiosity. Computers are driven by their instructions, and feel nothing. When the instructions end, they stop. We humans are endlessly driven by emotion, by feeling or wanting. Those who know Kocinski well say that when he tells his own story, that of the frustratingly hyphenated career in GP racing, tears squeeze up out of his eyes. Emotion is powerful, and this man has power.

The fact that his own nature and accidents of history have so far prevented him from definitively demonstrating that power has caused him, I suspect, a >

lot of internal suffering. It may sound corny to say it like this, but this man has suffered for his art.

Not everyone intuitively understands social conventions and interpersonal relations. I know this myself, because in return for what

understanding I have of machines and physical processes, I have a correspondingly weaker understanding of people and what makes them tick. In myself, this lack sometimes makes me feel like a man from Mars, only posing as a human. I have a phrasebook and a 250-word Guide to Human Behavior in my pocket, and it’s not enough. Kocinski delivers-he copes with the physical side of motorcycle racing brilliantly. It’s the social side that can be hard.

Other racers have had similar problems. Eddie Lawson had a bad spell with Yamaha-he complaining to the press about the bikes, Yamaha trying to repair the damage with honeyed words. Anxiety sharpens human nature, and racing at top level-especially for Americans in unfamiliar Europeis an anxious business. As I’ve said >

before, the war hero who single-handedly knocks out an enemy machinegun nest and takes Hill 603 is sent home to spearhead the bond drive, but the racing hero is expected to take Hill 604 next week and keep right on taking hills all season-while being pleasant to everyone and signing autographs. If he stops winning, he becomes invisible, maybe unemployable. Small wonder if these people are tightly wound.

I asked Kocinski to compare the Ducati he rode last year with the RC45 Honda. Giving me a direct, earnest look, he said, “Motorcycles are a lot like people. They all have different personalities. A Twin’s power is smoother than a Four, they aren’t so upset by bumps...” But before he could expand on that promising theme, Hondaline returned for a fairly extensive message.

History is safer than the present; I related a Kenny Roberts story, about being off the pace at Brands Hatch years ago, of running laps in his head in private, playing back all his moves mentally, frame by frame, and understanding what he had to do. KR set a new track record later that day. I had to respect that, I said, the ability to think of a plan, then turn it into a lap record.

“Talent,” Kocinski said. “Yeah, I do a lot of thinking, looking at section times.” And anyone on paddock row could see Kocinski’s long conferences with mechanics and the computer after each practice session.

I asked about differences in tires. Michelins, I suggested, look like they have superior grip at full lean, but must be less good at partial lean because their riders wait to accelerate,

then pop up to do it. Michelin-sponsored Kocinski started to say that Dunlops “steered a little better,” then steered himself back to safe ground, announcing that Michelins were clearly the tires to have. He would make it true on Sunday.

The conversation, or the lack of it, was frustrating, but that wasn’t the point. Kocinski wants this ride-and the 500cc GP ride that may follow-so intensely that he is willing to discipline everything he does and says toward that end. He knows that Honda is the king of resources; if any company can make a bike handle, give it power, confer reliability, Honda can. From here, there is no higher court, no place of refuge, no appeal. He has to make this deal work, because there won’t be another.

No human being can decide overnight to become someone else. As one of the Castrol Honda managers said, “The more pressure you put on a rider’s behavior, the more likely there are to be personality defects.” This is the voice of experience. All teams, all manufacturers, depend for their livelihood on positive public image, and must work to maintain it. A glance at the sports page shows that our heroes often require such “guidance.” But guide too hard and your efforts may backfire.

For the moment, the invisible covenant between Kocinski and Castrol Honda is working well, and winning races makes it easier on both sides. We all want to see him enjoy the full fruits of his remarkable qualities.

After the Laguna races came the press conference. Kocinski said, “This track is different from any of the ones we race on in Europe. It’s never easy to win. When I caught up to the backmarkers, I had 2 seconds (on second place). Then I lost 1 second, then I got it back. Last year, I lost the World Championship by 32 points, and now I’m only 4 points out.”

Then, more Hondaline. Cutting in, the Castrol Honda media officer asked, “John, what’s the key to Laguna?” Kocinski ignored the question, moving into a detailed comparison of Honda’s position last year and this, with wins to date and championship standings. “Now there are two Hondas in the top three, and they’ve never been in that position before,” he pointed out. It was a smooth performance.

As the conference broke up, and the three podium finishers filtered toward the door, through the crowd of journalists a man approached Kocinski, notebook and pencil ready, firing questions. “I can’t talk to you,” Kocinski said in real alarm. “No side interviews unless they go through Neil

Tuxworth.” He pulled me over. “Tell this guy, Kevin, you know, how it works.” The notebook retracted.

Kocinski turned back to me. “Remember what you were saying before, about (sliding) both wheels?” he asked. “Did you see those big slides I was gettin’ every lap? I rode harder in the second race. I was getting onto a pace. That’s where I excel: When the other guys are gettin’ tired. I’m not. I train hard.”

Soldiers say, “Train hard, fight easy.” You could see it. Kocinski had the stamina to keep his skill at work, the pressure on. Two laps from the end, one of Fogarty’s feet flew off the peg at the bottom of the Corkscrew. At the press conference, Fogarty candidly said, “I’m knackered. I feel awful and I just want to go home.”

At the end, Kocinski took two victory laps, standing up, waving to the crowd, punching the air. “Did you hear the people?” he asked the TV interviewer. “Did you hear them? They made me a better person today.”

At Laguna Seca, in more ways than one, John Kocinski had come home. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontPlan 2003

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

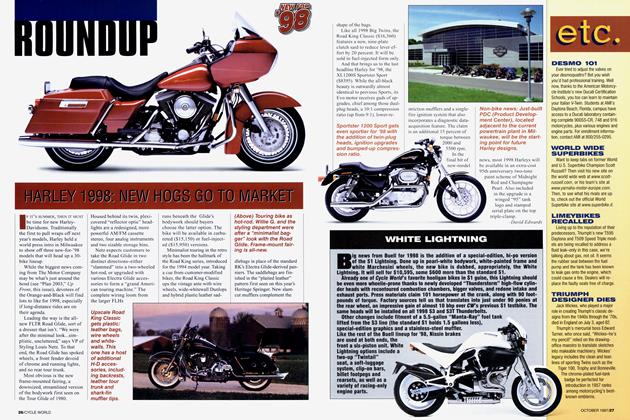

Roundup

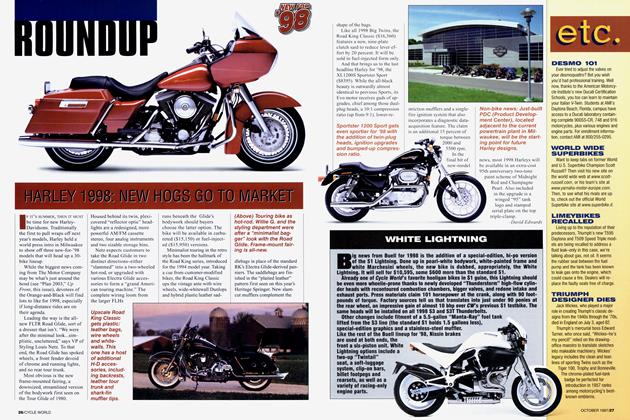

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997