SOLE PROPRIETOR

RACE WATCH

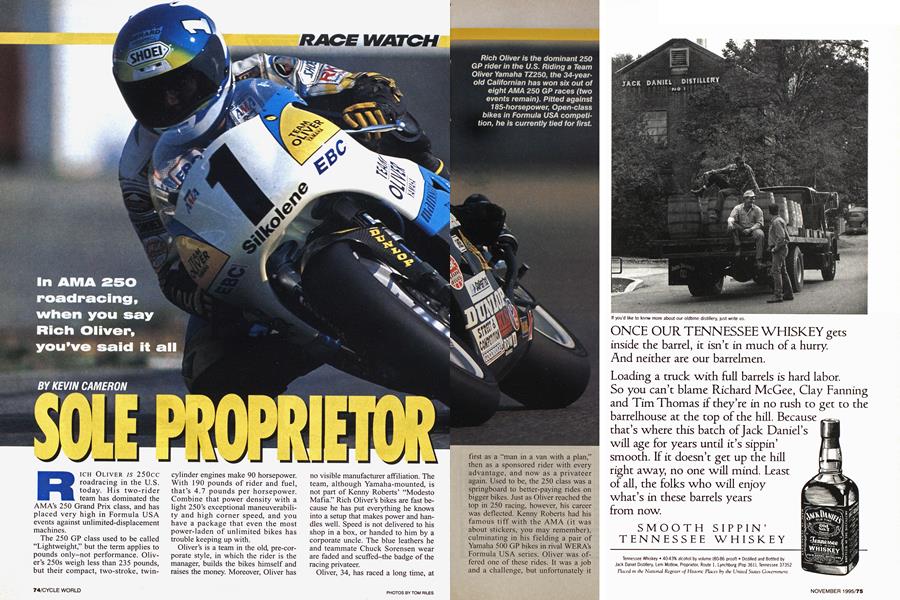

In AMA 250 roadracing, when you say Rich Oliver, you've said it all

KEVIN CAMERON

RICH OLIVER IS 250cc roadracing in the U.S. today. His two-rider team has dominated the AMA'S 250 Grand Prix class, and has placed very high in Formula USA events against unlimited-displacement machines.

The 250 GP class used to be called "Lightweight," but the term applies to pounds only—not performance. Oliver's 250s weigh less than 235 pounds, but their compact, two-stroke, twincylinder engines make 90 horsepower. With 190 pounds of rider and fuel, that’s 4.7 pounds per horsepower. Combine that power density with a light 250’s exceptional maneuverability and high corner speed, and you have a package that even the most power-laden of unlimited bikes has trouble keeping up with.

Oliver’s is a team in the old, pre-corporate style, in which the rider is the manager, builds the bikes himself and raises the money. Moreover, Oliver has

no visible manufacturer affiliation. The team, although Yamaha-mounted, is not part of Kenny Roberts’ “Modesto Mafia.” Rich Oliver’s bikes are fast because he has put everything he knows into a setup that makes power and handles well. Speed is not delivered to his shop in a box, or handed to him by a corporate uncle. The blue leathers he and teammate Chuck Sorensen wear are faded and scufifed-the badge of the racing privateer.

Oliver, 34, has raced a long time, at

first as a “man in a van with a plan,” then as a sponsored rider with every advantage, and now as a privateer again. Used to be, the 250 class was a springboard to better-paying rides on bigger bikes. Just as Oliver reached the top in 250 racing, however, his career was deflected. Kenny Roberts had his famous tiff with the AMA (it was about stickers, you may remember), culminating in his fielding a pair of Yamaha 500 GP bikes in rival WERA’s Formula USA series. Oliver was offered one of these rides. It was a job and a challenge, but unfortunately it

led only sideways, not upward. The dominance of the Roberts 500s was resented by other F-USA competitors, and in time, the bikes were withdrawn. Oliver struck out on his own, starting over-with a 250 again. At the time, he seemed like a lost person, polling those who might have useful information, racing out of a van again, trying to build a team out of not very much.

He clearly knows his business. Today, the professionalism-and especially the consistent results—of his team would do credit to any factory. As I walked up to Oliver’s setup at New Hampshire Inter-

national Speedway, there was the expected long trailer, resplendent in gleaming paint. There was a latemodel tow vehicle. Two uniformed mechanics were at work on two Yamaha

TZ250s, an awning protecting them from the New England sun, if not the springtime heat and humidity. Oliver set out two chairs in the shade and we talked about racing.

He noted that the 250 class has lost some top people this year-Jon Cornwell, Danny Walker and Chris D’Aluisio have left the field. He expressed the hope that, should the AMA decide to abandon its new 125 class (created in the heat of the AMA/Roger Edmondson struggle last winter), some of its riders would consider 250 racing.

Of course, when trackside regulars discuss 250 racing, they point to Oliver’s dominance and wish out loud that he would “give us some Cadalora finishes.” GP star Luca Cadalora liked to play with his rivals in 250 races, pulling out sensational last-lap wins. Years before, at the old Laguna event, GP stars Mamola and Roberts would agree ahead of time to play-race for most of the event, pulling wheelies and trading the lead. Then they would race seriously for the last five laps. Performances such as these, some believe, would add excitement to the AMA’s 250 program. Oliver’s reply to this was immediate and crisp.

“It’s their responsibility to come up to my level and race with me, not my responsibility to go back there and race with them. I have to look at this as a business. When I get 2 seconds in the lead, that’s capital I’ve earned; the only thing that can happen, other than

winning, is to lose it. I can only lose. So for that reason, I don’t want to be in there with the others and take any chance of falling down.”

This is pragmatism, and it permeated our conversation. But when I asked Oliver how he came to motorcycle racing, he showed an unexpected side of himself—as a romantic, emotional being quite different from the practical builder/rider/manager.

“My parents didn’t want any risks. No slingshots, no tree climbing; they thought I’d put my eye out,” Oliver remembers. “But I wanted anything that would go-Hot Wheels, slot cars, a motorcycle. I got a paper route, saved $450 and bought a little CT70 Honda. Then I learned to ride it at an abandoned Army transfer camp near where we lived. On its speedometer, that little bike would go 54 miles an hour. My favorite thing was to lean way forward, standing up so I couldn’t see the bike, like it wasn’t even there. Then it was just me, flying along over the ground.

“It took me 20 years before I could get that same feeling on my racebikc, that there’s just me and the contact with the bars, the seat, the pegs.”

As always happens when one person dominates a class, Oliver and his bikes generate gossip and rumors. Depending upon who is speaking, you will hear that Oliver has a pipeline to the factory, or to Bud Aksland (Roberts’ engine-development man), or to unnamed persons. Or you hear that he has special cylinders (or pipes, or ignition boxes, or whatever you prefer), obtained in some cloak-and-dagger fashion. Some believe the bikes have exceptional top end, while others say they excel in bottom acceleration.

What do the rumors mean? Only that winning performances get attention, and that people prefer complicated explanations of success-gadgets, or friends in high places-over the obvious, simple explanation: that Oliver is good enough to have earned it.

As you’d expect from a person who began racing before the recent era of street-based racing machines, Oliver’s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBurke's Bike

November 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafe Racing

November 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCExtremes

November 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1995 -

Special Section

Special SectionCalifornia Specials

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

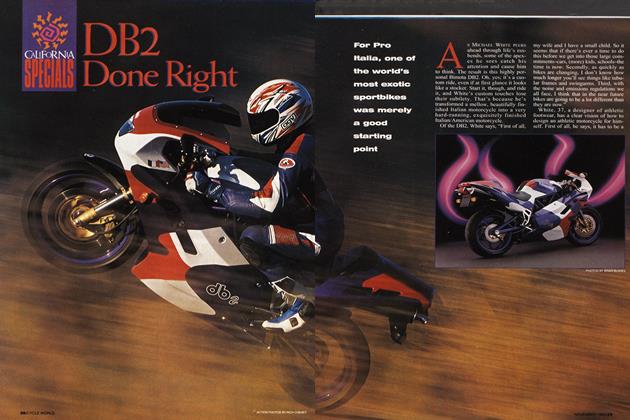

California Specials

California SpecialsDb2 Done Right

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson