ADVANTAGE EKINS

Racer, restorer, stuntman, elder statesman, Bud Ekins has done it all

JOE SCALZO

BEFORE THERE WAS LENO, BEFORE THERE WAS LETTERMAN, TV’S TOP-DOG talk artist was Johnny Carson. And during one midnight gab-fest back in 1963 the top-dog talker was making nice with Hollywood’s top-dog tough guy/bad hombre, Steve McQueen. Carson was beside himself flattering McQueen for the way the actor could ride a motorcycle, for the way McQueen had air-mailed a Triumph 650 over a barbed-wire fence in The Great Escape.

“That wasn’t me,” McQueen interrupted. “That was Bud Ekins.” Hollywood’s tough guy/bad hombre coming on modest, admitting he’d employed a double? Then violating all convention by mentioning the lowly double by name?! Cut to commercial!

Two things: 1) On and off the screen, Steve McQueen was the real deal, a tough guy/bad hombre who was white-knuckle serious about it; 2) Out on the wide-open Mojave with 400 pounds of desert sled between his legs, McQueen was equally the real deal-he could hare and hound a storm. Probably the role of motorcycling’s top-dog racer was the one he most lusted to play. McQueen, in short, wanted to be Bud Ekins.

Well, cool. Who didn’t want to be Bud?

Responding nostalgic pronounced to a question like about that, his like racing the triple career, thump Budbudbud-which of his Matchless sounds G80 winning the Greenhorn Enduro-played it ultra-modest. “I had advantages,” he replied, which actually was a fairly long-winded answer coming from Bud Ekins. Continuing, he pointed out that he always had the right connections. His sponsors at Matchless and later Triumph kept him in top iron. Johnson Motors, Triumph’s arm in California, paid him a $50 bonus every time he won, and even gave him his own dealership.

All true enough. Bud, however, neglected to mention certain other advantages, the ones that really counted. Bud at his top-dog peak was a Dick Mann-type, meaning he was just an average guy, though not an ordinary one, and free of any of that I’m-so-talented jive. He was a Joe Leonard-type, with killer good looks. He was a Sprouts Elder-type, tall, loose and spindly with the reflexes and bearing of a star athlete. He was an Iron Man Ed Kretz-type, who never got winded. He was a Gary Nixon-type, who instead of being some sickeningly wholesome goody-twoshoes poster boy, had an appetite for the minor vices, i.e. coffin nails and booze (bartender, another J&B rocks).

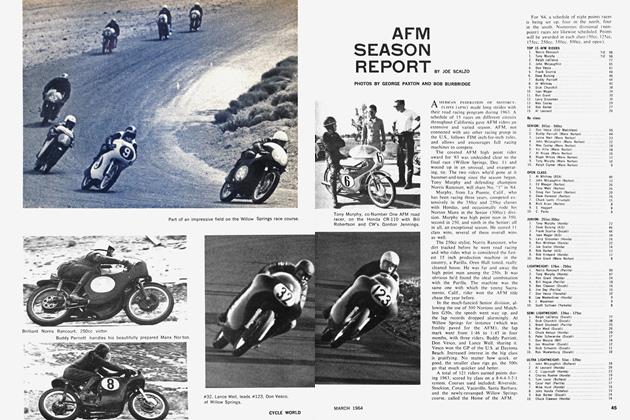

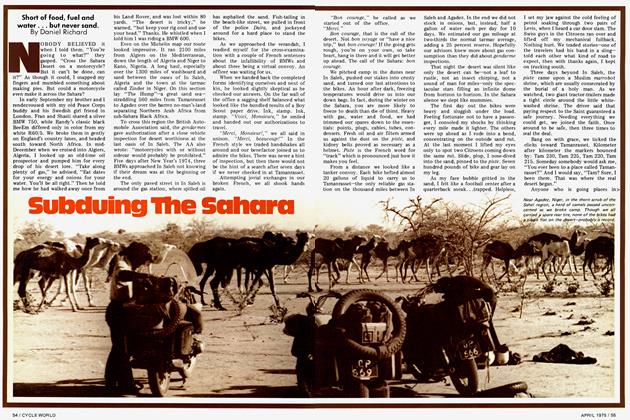

It was a great motorcycle civilization that Los Angeles had going on in the 1950s and 1960s, and one of the hottest deals was getting to watch Bud patrolling the scene at the Greenhorn, Big Bear and Catalina. It’s a trick question, but do you know what these three famous meets, all great yet utterly different-the one a grinding two-day enduro/rally across the rocky hell’n’gone of the Rand and El Paso mountains, the other the universe’s mightiest hare and hound, and the third a fabulous scrambles/roadrace that was California’s version of the Isle of Man, except it took place on a hip and sunny blue island without any gore-do you know what these three classics had in common? Bud! His name was all over them. Who else ever won all three, some of them more than once?

Most racers tend to nail one or two forms of competition, master them, and ignore the rest. Bud’s twin passions being scrambles and high-speed desert work, the Greenhorn Enduro really shouldn’t have been his deal. It was one bitchin’ desert ride, all right, but just

when you realized you were having lots of fun

gassing it, it was too late, you’d already blown a checkpoint, because the 500-odd miles had to be traversed perfectly at set speeds. Go too fast, you failed. But when they posted the results the next morning, he’d won the sucker! “I was surprised,” said Bud, sounding just like Bud.

He was always more comfortable at Big Bear, and never more so than in 1959, when he did a huge and embarrassing number on the run’s thousand-odd desert sleds and tied wily old Aub LeBard as a three-time champion. Following the usual Oklahoma Land Rush to the smokebomb, Ekins and his Triumph 650-a duplicate of the one he later used in The Great Escape, except that its skidplate armor made it even more ponderous-were leading until flattening a front tire and having to root hog to the first gas dump through five miserable miles of sandwash. The pit crew put on new rubber and got Bud going again, but minus the front brake and no longer leading. Time for some serious motoring. “Shift a gear, lose a bikelength,” was the Mojave mantra, so Bud didn’t. Bolting his 6-2, 160pound carcass to the back fender to pick up the front wheel through the dust, he caught fourth cog and maintained an Ekins-type 90 mph across the boondocks.

Regaining the lead, he crossed the finish line up in the high mountains at Fawnskin, sending the snow flying. But where was second

place? A minute passed, 2, 10, 15. By then, Bud had changed into his street threads and had burned half a dozen coffin nails. At last, following a wait of 22 minutes, second place arrived. It was Jim Johnson, Ekins’ pal, aboard another Triumph, a 500 tuned and prepped by Bud.

And how about this? In 1955, after many previous attempts and breakdowns while leading, Bud-from a distant 98th starting hole-won the Catalina GP. It was a huge score, but there was to be an even greater epilogue. Just a month or so afterward, passing through New York state on his way to the Olde World for a summer of British scrambles and motocross meets on the Continent, Bud by chance dropped in on the national scrambles at Crotona Snow Valley. The Triumph contingent there recognized his name as the Catalina winner, and one of its members loaned Bud a TR-6, so brand-new it still had its muffler and headlamp. Removing them, Bud the visiting fireman from fruit-and-nuts L.A. ambushed elements of the proud Pink family, an East Coast dynasty of Milwaukee Vibrator heroes, and carried away the grand national.

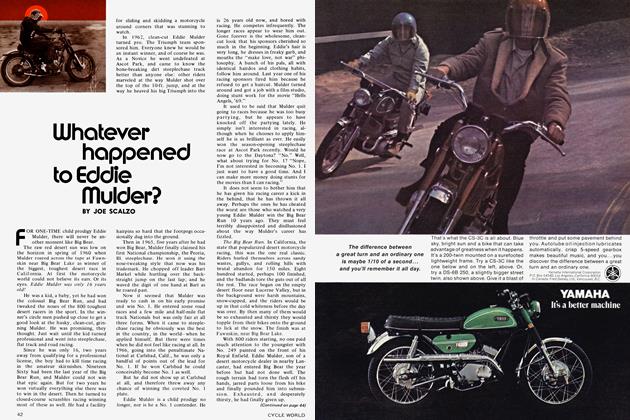

round 1969, long after Greenhorn, Big Bear, Catalina and the whole cult of the desert sled had ended, and Bud himself had split the L.A. scene to hang with McQueen and

work movie and TV stunt gigs, Eddie Mulder telephoned, saying something like, “Hey, Uncle Bud, get ready to put yourself back in the grinder. You and I are taking a couple of your old 650s and we’re going to set a new Ensenada-to-La Paz motorcycle record.” Mulder had long since made his own legend when, aged barely 16, he’d won Big Bear. Quite naturally, Bud found it impossible to say no to the closest thing to a protégé he’d ever had. So he and Squirrel proceeded to bum up Baja in 32 day-and-night hours, getting their record. En route, Bud holed his oil tank, then lost all lubrication-or maybe it was a primary chain that locked-and supposedly hit La Paz dead-engine with Mulder pushing with his boot.

As already noted, Bud isn’t one of nature’s motormouths; consequently, Squirrel’s version of this mad parable is far more colorful than Ekins’ version. Bud’s the same way on most topics. I spent a lot of time third-degreeing him about his beginnings, and how it was he got to lead what many might consider the ultimate motorcycle life. Had he been bom under a lucky star or what? I never persuaded him to fully open up. Who was it that said, “The more you talk about something, the more you kill it?” Hemingway? Bud himself? Somebody who may be on to something.

Whatever, breaking into that magical L.A. biker civilization of almost half a century ago and getting in on its action wasn’t easy; it required entry-level smarts. Growing up in the Hollywood Hills near Lookout Mountain, Bud observed his father, a kind of wildcat oil operator, cutting up old cars and selling the scrap iron for three or four bucks. That was Bud’s cue to leam about tools.

Then, at 16, he encountered a VL-model Harley that one of his cousins had disassembled and couldn’t reassemble. Putting everything together again, Bud rode off on it.

Frank Cooper, the Matchless importer, liked what he saw and made Ekins shop mechanic. By then, Bud was making his racing bones the old-fashioned way, zapping the fireroads above Hollywood. “Let’s go ride a hare and hound,” somebody suggested. “What’s that?” inquired Bud.

Never developing the hots to be a street rider, Bud instead trolled L.A. boulevards via hot-rod. One night, he’d just pulled his trick T-bucket into the Bob’s Big Boy on Riverside Drive when in rolled something more trick still: A zooty 1936 Ford Club Coupe complete with Carson top and tooled by a looker named Betty Towne, whose parents were movie people, her dad being one of the city’s hot screenwriters and her mom a former Zigfield Follies hoofer. Bud and Betty subsequently married and for 46 years, until Betty’s premature and wrenching passing in 1996, were royalty among L.A. bikedom couples.

Greenhorn, Big Bear and Catalina were great-they were

SoCal’s triple crown-but testing his mettle an ocean and a continent away in the scrambles and motocross tournaments of the U.K. and south of France was where Bud most wanted to be the rest of the time. The Matchless factory gave him the nod, and a works bike. He raced well. The U.K. gave him an enduring appreciation for Irish ale; on the French Mediterranean was where he discovered Gauloises smokes.

One afternoon, he and his G80 were hauling the mail through one of the Emerald Isle’s gullies when a squad of Triumph factory riders ate him up on both sides. Bud realized it was time to park the Thumper and switch to Edward Turner’s buzzbomb vertical-Twins. Back home again in L.A., Johnson Motors obliged him and then, almost as an afterthought, inquired if, aged 25, Bud cared to become the USA’s youngest Triumph dealer.

The very first motorcycle Bud ever sold was a combination of himself and the customer working together to fill out a sales form. But by the time he got out of the business in the 1970s, Ekins was reputed to be moving more Triumphs than anybody in the world. His shop on the comer of Ventura and Van Nuys was perhaps the city’s most live-wire and “in” emporium. Bud, top-gun racer, worked the sales floor, but without the old hard-sell. Eddie

Mulder’s father AÍ managed the parts department. And in the backroom, Kenneth Howard, the genuinely weird painter and customizer who called himself “Von Dutch” (one of his claims was that he’d been the youngest pigboat commander in the Führer’s navy) artistically pinstriped gas tanks and helmets while bombed out of his mind on cheap Thunderbird and lacquer fumes.

Sunday was Bud’s big racing day, also big play day. The routine was straightforward: Rise and shine in the early a.m. and commute to, say, the hare and hound over at Red Rock Canyon. Win it. Then ramp the scooter into the bed of the pickup-no time to tie it down, just let ’er flop-and gather up Betty to boogie over to Acton for the afternoon scrambles meet. Win it, too. Be home by evening for the celebratory J&B rocks.

Perfect...

Hollywood was on a first-name people were basis regularly with heavies in and like out of Lee Bud’s Marvin shop-he (“Chino” of The Wild One)-but the starstruck business is junk, and Bud never played hanger-on. So, seeing Steve McQueen for the first time-it must have been around 1960-wasn’t a big deal. All McQueen wanted to do was take over ownership of either a TR6 or a Bonneville originally purchased by the son of movie star Dick Powell, whose wife had ordered him to get that thing out of the house. But one thing inevitably led to another. Turn me on to desert racing, McQueen said-or, in so many words: Make me like you.

Bud obliged. He built McQueen a desert sled and the two of them began riding/racing together. There was none of that “close as brothers” malarkey, but their birthdays fell only a couple of months apart and neither one liked losing at anything-whether it was going behind the Iron Curtain and having their butts busted in the ISDT or just getting into what was supposed to be an innocent duel pitching pennies. McQueen couldn’t ride the way Bud did, but he rode well and was willing to pay the dues. Called on to present an Oscar at an Academy Awards, Steve did so with one of his paws in plaster from a tête-à-tête with a puckerbush the Sunday previous. Mainly, though, he emulated Bud. Ekins, for one example, had amassed this gigantic vintage collection-54 pre-1916 U.S. marques alone-so McQueen accumulated one, too. Von Dutch, Bud’s old employee, was one of its caretakers.

McQueen had Bud dye his hair to double him in The Great Escape. And Steve-not to mention Johnny Carson-was so blown away afterward that he broke all the old Hollywood rules by going public with Bud’s name. Go rent The Great Escape from the oldies-but-goodies bin of your closest video emporium. Sit patiently through all the other stuff, then slo-mo the VCR while Bud does his thing. You may well ask: These 1990s-style daredevil/megalomaniacs are cannonballing high-firepower and heavily cushioned rocketships over the edge of cliffs and sailing clear across canyons, so what’s so hot about jumping a mere 60 feet? All due respect to today’s laddies, but Bud’s mode of transport had 38 horsepower max and was a dinosaur weighing almost a quarter of a ton. Oh, and despite having zip suspension under him, Bud, upon landing, didn’t wipe out.

After that, a fresh career opened up as stuntman and stunt coordinator (more “advantages”). Having greased what was arguably the first and preeminent motorcycle leap in The Great Escape, Bud, seven years later, was asked to fly a 390 Ford Mustang off the skipramp streets of San Francisco in Bullitt, that terrific cops-and-robbers flick featuring film’s original hyperactive car chase. Psyching himself up beforehand with the conviction that “anybody who. can race a motorcycle can drive a car,” Bud aced the Bullitt action, the slam-banging of the poor Mustang audible for blocks. Again, he was doubling McQueen. This time, though, McQueen was far less willing for Bud to get the credit, as I unfortunately discovered after an automotive magazine published an article I wrote, spilling the frijoles about Bud’s uncredited part in the movie. Reading my story,

McQueen went ballistic. Then he telephoned, promising he was

going to have his studio hatchetmen beat my brains out, or maybe do it himself, plus have his shysters clobber me with a barrage of lawsuits. For years afterward, I tensed at the sight of a green Mustang.

McQueen’s demise to the Big C was pathetic, as were most of the subsequent biographies that sordidly described the desperation of the actor’s final days. For his part, Ekins remains a rock who refuses to divulge any confidences about his old friend and surely most rabid fan. Bud, in fact, is like Joe Petrali, the great hillclimber and aide-de-camp of billionaire Howard Hughes, who went to his own grave loyally refusing to speak an unkind word about his demented boss.

Today, the Mulholland Ekins, 69, fire lives station, off Nichols in an old Canyon, and smashing close to three-story house. Its dirt basement once contained artifacts of vintage bikes, but what with the breaking up and selling off of his collection, one of the few antiques left is “Turtle,” the baby tortoise-long grown into a monster-that he picked up during a Greenhorn and brought home for a pet. The Manse Ekins represents Bud’s nighttime and morning digs; afternoons, he flops and holds court at his garage hideaway in North Hollywood. “I’m all that’s left of the real Bud Ekins,” he says.

Point taken. Having been the real Bud Ekins for so long, costs are now coming due. Crying out for attention are old hurts like a blown knee (he sometimes uses a cane to get around), along with a kinked arm (from the pitch-black night in Baja when he and McQueen were interesting themselves in off-road cars and Bud took a dune buggy end-over-end to the bottom of a mountain).

Plus, he isn’t sure where that spacious front porch of his suddenly came from.

But he’s undeniably the real Bud Ekins, meaning that his phone rings a lot. Sometimes it’s one or both of his daughters, doyennes of the business side of the film industry, calling to chat up the old man. Sometimes it’s a collector asking if Bud has any great old bikes for sale, or knows where any are located. Sometimes it’s museums like the Guggenheim, asking Bud’s help for the recent show. Sometimes it’s somebody from one Hall of Fame or another, announcing Bud’s just been inducted. Sometimes it’s long-distance, person-to-person from London-the organizers of a high-toned and hoity-toity blacktie car and bike concours d’elegance offering business-class airfare and expenses to fly over and be a judge.

Lots of bodies are in and out of the garage, too, many of them remnants of that great old L.A. bike world still showing up to pay the top-dog his deserved regard and respect. But one afternoon recently the traffic got a little thick, including a film crew from a TV company planning a cable special about Bud, and even a couple of reps from the scheming yellow print press-one of them myself-asking for interviews. Bud being Bud, he can’t help exuding good cheer to all, yet somehow he didn’t like the smell of it. Setting fire to another Gauloises, cracking open a can of high-test cappucino, he wondered aloud, smiling, if all the attention and adulation and fawning meant that we might be getting ready to scrub him down for the last rites or something. If so, we could kindly take a hike, he’d already made his plans. He was going to be around for a long time.

I got my interview, delivered my thanks, and while Bud went off to rent a monkey suit for the London concours, I went home, loaded Bullitt into the VCR, and spent the rest of the afternoon digging he and the flying Ford Mustang.

“I’ve had advantages,” Bud said.

Sure. He’s Bud Ekins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Teabag Chronicles

September 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSlow Seduction

September 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSubject To Change

September 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 1999 -

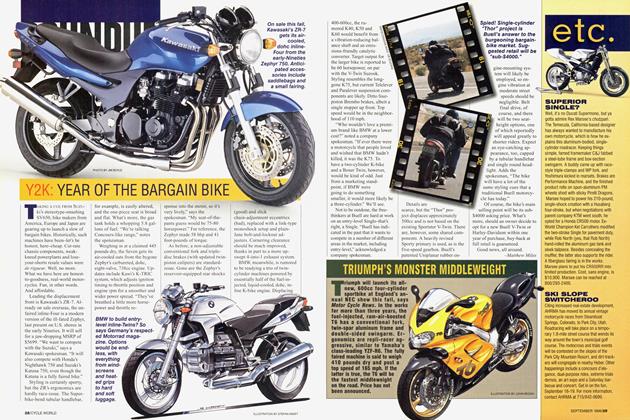

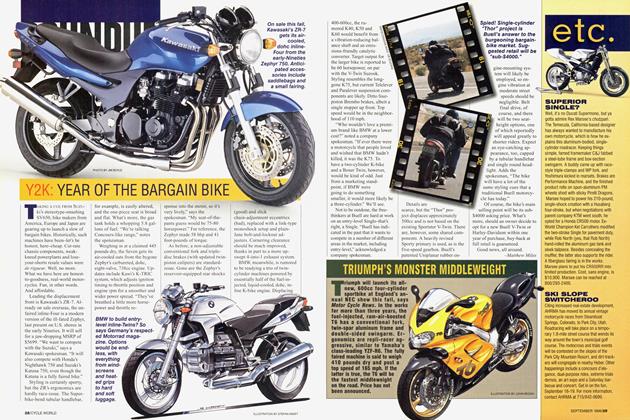

Roundup

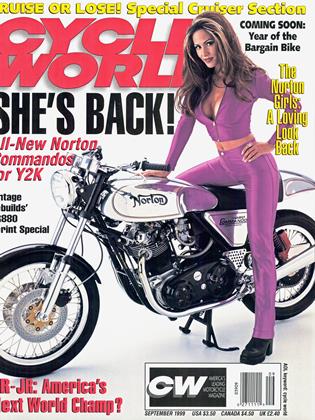

RoundupY2k: Year of the Bargain Bike

September 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Monster Middleweight

September 1999