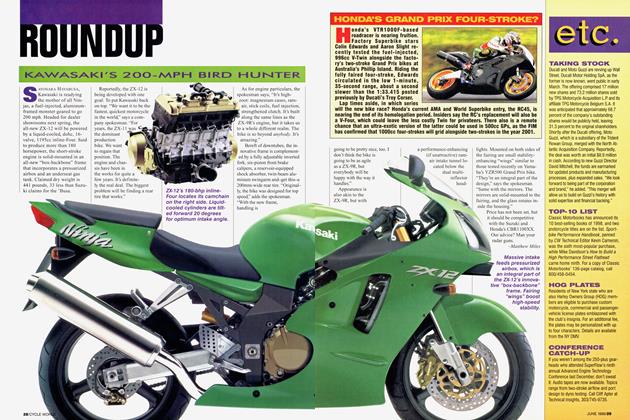

Deconstructing Daytona

For Harley-Davidson it was the worst of Daytonas, for Honda the best

KEVIN CAMERON

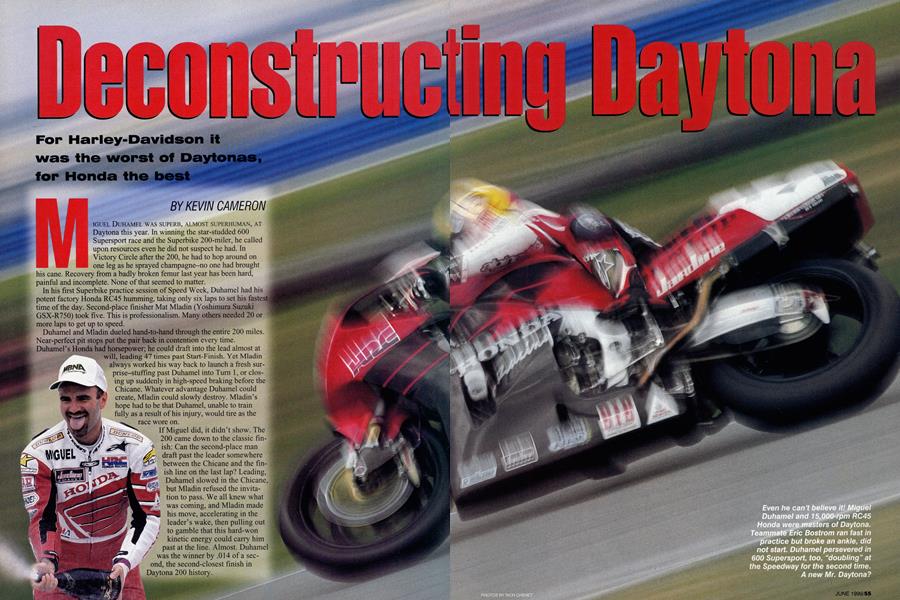

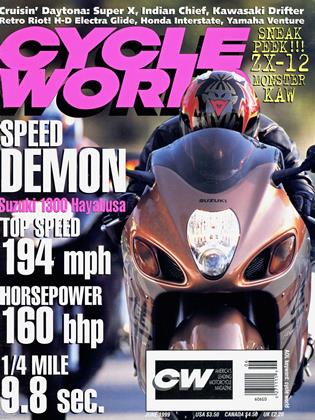

MIGUEL DUHAMEL WAS SUPERB, ALMOST SUPERHUMAN, AT Daytona this year. In winning the star-studded 600 Supersport race and the Superbike 200-miler, he called upon resources even he did not suspect he had. In Victory Circle after the 200, he had to hop around on one leg as he sprayed champagne—no one had brought his cane. Recovery from a badly broken femur last year has been hard, painful and incomplete. None of that seemed to matter.

In his first Superbike practice session of Speed Week, Duhamel had his potent factory Honda RC45 humming, taking only six laps to set his fastest time of the day. Second-place finisher Mat Mladin (Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750) took five. This is professionalism. Many others needed 20 or more laps to get up to speed.

Duhamel and Mladin dueled hand-to-hand through the entire 200 miles. Near-perfect pit stops put the pair back in contention every time.

Duhamel’s Honda had horsepower; he could draft into the lead almost at will, leading 47 times past Start-Finish. Yet Mladin always worked his way back to launch a fresh surprise-stuffing past Duhamel into Tum 1, or closing up suddenly in high-speed braking before the Chicane. Whatever advantage Duhamel could create, Mladin could slowly destroy. Mladin’s hope had to be that Duhamel, unable to train as a result of his injury, would tire as the wore on.

If Miguel did, it didn’t show. The 200 came down to the classic finish: Can the second-place man draft past the leader somewhere

between the Chicane and the finish line on the last lap? Leading, Duhamel slowed in the Chicane, but Mladin refused the invitation to pass. We all knew what was coming, and Mladin made his move, accelerating in the leader’s wake, then pulling out to gamble that this hard-won kinetic energy could carry him past at the line. Almost. Duhamel was the winner by .014 of a second, the second-closest finish in Daytona 200 history.

There was more racing to come. A minute back, Yamaha-mounted Rich Oliver was planning a similar move on roadracing’s number-one plate-holder, Vance & Hines Ducati’s Ben Bostrom. It worked-by less than a wheel-making Oliver third, Bostrom fourth.

We had come to Daytona hoping for great things from the new alliance of five-time 200 winner Scott Russell and the fast-maturing Harley-Davidson Superbike. In pre-season testing, the VR1000 had improved rapidly and, despite a tangle of irritating and petty problems that never went away, the bikes were genuinely fast in Daytona practice. There was to be no result, however. Russell was badly beaten up in a bar fight Thursday night. With broken facial bones and a rumored

detached retina, he was unable to ride. Pascal Picotte, who had qualified 11th on the other factory Harley, crashed in Tum 1 on the 10th lap.

A new 1:48.516 qualifying record was set by Mr. Controversy himself, dashing Anthony Gobert on the second V&H Ducati 996. He would finish 11th. Just for the record, no Superbike Twin has ever won the Daytona 200. The reason, I believe, is that Ducati tailors its

reliability to the races that matter most to them: World Superbike. If one of the desmos wins Daytona, so much the better. The Japanese companies, on the other hand, have always valued Daytona wins for their effect on U.S. sales. Honda’s approach to reliability is to require its race engines to survive a grueling bench

test. This is a dyno simulation that begins at 6000 revs, winds through the gears, holds full throttle/maximum revs for 15 seconds and repeats-for 20 solid hours! If there is a failure, red lights flash and alarms ring, bringing engineers sprinting to analyze the problem, prepare redesigned parts and repeat the test. This parallels the kind of testing applied to aircraft engines since the 1920s. It’s expensive, but it creates engines that continue to fire.

Who had the power? Backstraight radar numbers may not be science, but they’re interesting. The Hondas of Duhamel and Eric Bostrom were fastest with clockings of up to 184 mph, but Doug Chandler’s Muzzy Kawasaki, though handling poorly early in the week, got through at 180. Suzukis and Ducatis produced a scatter of 178s and 179s. Scott Russell had two 179-mph clockings on the Harley. How much air are they pushing? I applied a tape measure and found that Japanese Superbikes are all 20 inches wide. The Ducatis measure only 18 inches, and the Harleys are close to 19.

During interviews of the top four qualifiers, Mladin posed a reasonable question: Why do Ducatis qualify so much faster than they run in the 200? Because Mladin set seven pole positions last year on Suzukis, you can choose to dismiss this question as one fast Australian needling another (Gobert). Ducati reliability is a yoyo affair. At the beginning of a season, we hear the engine-mileage guarantee is 360 miles. By season’s end, it drops to half that as riders must swing the tach needle harder to make the lap times. Then, re-engineering builds it back up again. This wouldn’t be the first time Ducati team managers have decided to go for reliability rather than ultimate speed here. In the end, Ducatis finished fourth and ninth through 11th.

What about Kawasaki riders Chandler and Aaron Yates? Finishing seventh and eighth, they were never major players, and handling problems were indicated. Yosh/Suzuki was solidly represented with Mladin’s close second, and by Superbike newcomers Steve Rapp and Jason Pridmore, fifth and sixth.

Fourteen large boxes, all labeled “Ruóte Marchesini,” blocked one end of the Harley garage. “Magnesium wheels don’t last forever,” crew chief Scotty Beach said cheerfully. “And that’s only half the order.” Every Superbike is an international mixture. The Harley has British AP sixpiston brake calipers and carbon clutch, Japanese Showa suspension, Italian wheels and Marelli fuel injection, ignition, engine control and data acquisition, and English Dunlop slicks. Team manager Steve Scheibe’s stated policy is to use the leading components in every field; this is what the successful teams do.

Last year, a fumbled pit stop negated Picotte’s sensational front-row start (he qualified only tenths off the pole, at a 1:49.235) and strong early pace. This year, quick-change rear wheels make such nightmares much less likely. Each wheel has a five-sided driver that drops easily and positively into a three-sided receiver driven by the sprocket. Unscrew the axle, snap it back, pull the wheel, drop in a fresh one, whack the axle in, hit it with the air wrench. The chain stays on the sprocket and the sprocket stays on the swingarm.

Honda, now running double-sided swingarms on its RC45 Superbikes, had a similar system. Honda team manager Gary Mathers said they can actually change the rear wheel faster now than with the single-sided arms.

“We’re waiting for the fuel to drop,” he remarked.

Up ’til now, Harley has always been open about everything it’s done-the six-speed transmissions, improved pistons and so on. Now, Scheibe said with some discomfort, there are areas in which they believe they at last have something to protect, and he would be unable to discuss these areas.

One visible change was the addition of a second sump-scavenge oil pump, located on the starter pad at the front of the engine. “Every year at Atlanta, we lose at least one engine (from oil moving forward, away from the pickup, as a result of downhill braking). This puts an end to that,” I was told. It may have another effect. In NASCAR, highvolume scavenge pumps and other devices (intake-manifold and headerjunction vacuum taps) pull crankcase pressure seriously negative, reducing the amount of oil being flung onto cylinder walls. This by itself accomplishes nothing. But if reduced-tension oil rings are used with this feature, the result is reduced friction. Private tuner Don Tilley, who has many friends in NASCAR, has used this for years.

“If you let it (case pressure) go positive,” he said, “then you’ll have to use 10, 12, maybe even 15 pounds of oil-ring tension to keep that oil out of the combustion chamber. That eats horsepower.”

While previous VR engines have used “showerhead” fuel injectors, located above the open throttle-body bellmouths, these were invisibly mounted on the underside of the seat/tank unit. Now they are attached to the bellmouths themselves. New carbon-fiber valve covers replace magnesium ones formerly used. New covers were needed to make room for stick-type coils (ignition coils made as part of the sparkplug caps), and since the VR team now has its own carbon fab shop, this was the natural (and lighter) way to do it.

It looked like rain as Superbike practice began. “I’d just as soon it did rain,” Scheibe said glumly.

“Work to do?” I asked.

“Some,” he replied.

I would soon see how much. Normally, VR engines are started with a hand-held starter that engages a square drive in the left-hand crank end. A pair of handlebars on the starter enables the operator to handle the torque. But now I was seeing another gadget-an aluminum box with hoses-being plugged in under the seat. Why? The normal electric fuel pump in the gas tank hasn’t been reliable (I would in the days to come see mechanics with their ears to the tank listening for its hum). A new mechanical fuel pump, driven by an Oldham coupling from the front oilscavenge pump, was being used, either in series with the electric pump, or by itself. But even that was troublesome.

Located among hot parts, the inlet to this pump was vapor-locking. The “gadget” I noted was a fuel booster pump, and it was in frequent demand. Although an engine might start without it, it could then stall. I wondered how the pit stops would be handled, and I had visions of an impatient Russell or Picotte accelerating down pit lane with this “Molotov cocktail” bouncing along behind.

On one occasion, an engine completely refused to start, running one starter dead so another had to be brought. While other teams got on with finding tire and suspension setup, the Harley men were locked into chasing down minor problems. As a result, Russell made very few laps, and his body language of controlled impatience was the talk of the pits. This team is in transition from being a small, do-ityourself operation, little different from well-funded privateers, to a new identity as a large, capable engineering group. They now have power and they have handling, but it’s taking time to stomp out the little problems.

Later in practice, Picotte would crash, possibly from a sticking throttle, and would also suffer two “engine unstarts.” Near the end of Russell’s Thursday p.m. qualifying session, observers were all sure he was at last about to hammer it for a quick lap. Didn’t happen. His engine gave a big POP going into Tum 1, then stuttered around the circuit to the pits. More vapor-locking? Russell reportedly said, “Don’t worry about it. We’ve got it (a good setup).” Then, taking off his helmet and carefully tucking his earplugs into its top vents, he strode away never to return. His best time as of that moment, a 1:51.454, nearly 3 seconds off Gobert’s pole, would put him 15th in qualifying. In the wee hours of the next a.m., he would suffer extensive facial injuries in one of the area’s freewheeling night spots.

Throughout practice and qualifying the Harleys were posting good times, and were visibly fast past StartFinish. Both riders ran with top Ducatis and with them handily or pull away. This is not a basically flawed motorcycle; it is an underdeveloped one. Scheibe’s innovations have often been organizational: First, he managed to have racing separated from product engineering. Engineering Department procedures may be accurate, but they are too deliberate for racing. Then he had the operation moved to its own premises, away from hallowed Juneau Ave. Next, Gemini Corporation was created to develop the engine, and comparative design was undertaken. Now he has discovered how much money other companies spend on racing in a year’s time-more than Harley has spent since the beginning, he says.

We have all noticed how small the team is, especially when you consider that they not only race the bike, but must design, manufacture and devel op it as well. No wonder there was no track-test program before September, 1998. No wonder there is no dyno-based durability testing now. Men can work three shifts, but not for long. In other companies, the products sold are the basis for their racebikes. Much testing and redesign can therefore be shared. For Harley, the VR is a stand alone program. Keeping dynos and computer workstations and machine tools running even when the team goes on the road requires more good people and the money to pay them. Why should Harley bother? The business reason for the VR's existence is that it offers the company an accelerated course in technologies that will become necessary for its production machines in future time. This is a good invest ment. Experience like this cannot be bought from consulting firms like Ricardo or Cosworth. The VR program could not have lasted as long as it has, winless, unless it were politically protected. That means that someone high up in the company believes, win or lose, in its worth.

That is courageous, and I hope the policy continues to the conclusion we all want to see-a fully competitive American Superbike. What next, fans want to know? Help is coming. On Wednesday of Speed Week, Harley announced a new pro motional alliance with Ford. This will inject serious money into the VR program. It needs it. Brilliant designs can come from individuals or small teams-consider

the work of John Britten-but brilliant results usually have to come from orga nizations with the financial muscle it takes to develop those designs quickly.

...... After the race, after the breath less hat-changing in Victory Circle, and after the pressroom arm waving, Miguel Duhamel sat quietly before his mother and father and other fellow Quebeckers, all speaking French. A king and his court.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue