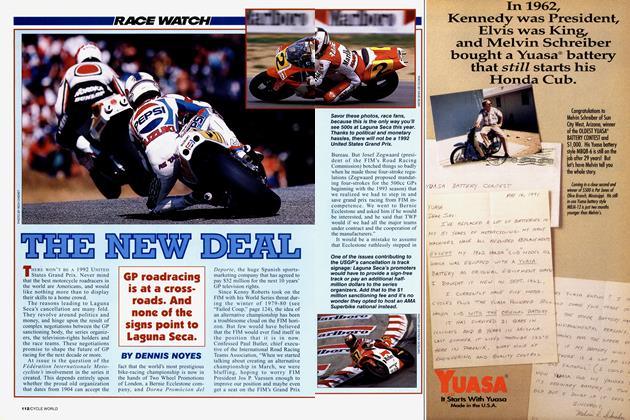

RACE WATCH

A PLACE CALLED PUKEKOHE

Half a world away, an enchanting speed festival embraces the humanity of vintage racing

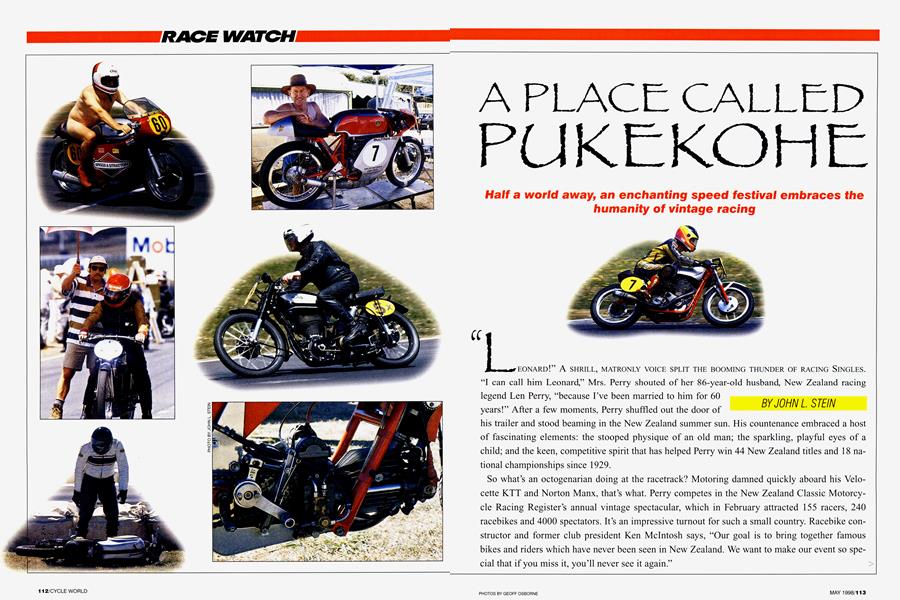

"LEONARD!" A SHRILL, MATRONLY VOICE SPLIT THE BOOMING THUNDER OF RACING SINGLES. "I can call him Leonard," Mrs. Perry shouted of her 86-year-old husband, New Zealand racing legend Len Perry, "because I've been married to him for 60 years!" After a few moments, Perry shuffled out the door of his trailer and stood beaming in the New Zealand summer sun. His countenance embraced a host of fascinating elements: the stooped physique of an old man; the sparkling, playful eyes of a child; and the keen, competitive spirit that has helped Perry win 44 New Zealand titles and 18 na -tional championships since 1929.

So what's an octogenarian doing at the racetrack? Motoring damned quickly aboard his Velo cette KTT and Norton Manx, that's what. Perry competes in the New Zealand Classic Motorcy cle Racing Register's annual vintage spectacular, which in February attracted 155 racers, 240 racebikes and 4000 spectators. It's an impressive turnout for such a small country. Racebike con structor and former club president Ken McIntosh says, "Our goal is to bring together famous bikes and riders which have never been seen in New Zealand. We want to make our event so spe cial that if you miss it, you'll never see it again." >

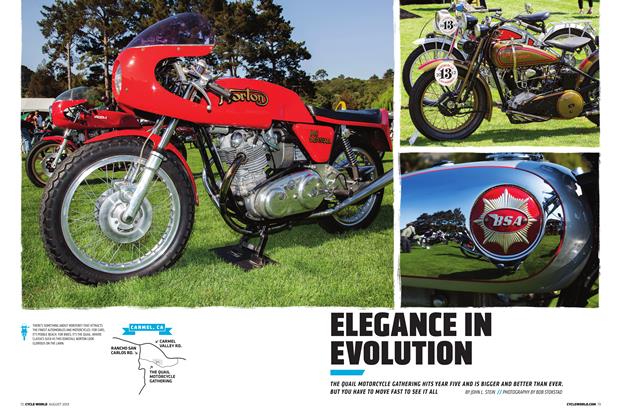

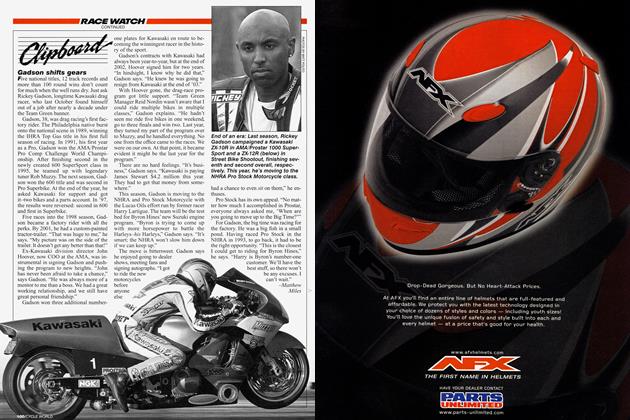

JOHN L. STEIN

The club may be onto something. This year, imported attractions included Paul Smart and his Imola 200-winning Ducati, and GP legend Arthur Wheeler and his 1953 Moto Guzzi 350 works Single. The event also honored 100 years of Norton: Examples ranged from a 1902 Ener-

gette to the last 500cc Manx built to a recent F1 Rotary.

Forty sprint races were run over a two-day period around Pukekohe’s 1.7-mile road circuit. Built in 1961 together with a horse-racing facility, the nearly flat circuit is amoebaeshaped-essentially an oval with a hairpin and esses at each end. At one time, Pukekohe (say “Pook-a-ko-ee”) was home to the Tasman Series car races, but it is known by most Americans as the place where Cal Rayborn lost his life.

What makes Pukekohe special is New Zealand’s polite and welcoming people, the circuit’s low-key environment, and the purity NZCMRR demands of its bikes. The rules allow vintage and replica machines, but period modifications only. A prohibition on Japanese equipment means two-strokes are the minority and British iron is the majority.

Pukekohe is a half-hour south of Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city. The surrounding topography is quite similar to coastal California-low, rolling hills, grassy meadows and a local economy based on farming. Tucked in on the backstraight, riders occasionally catch the pungent scent of fresh-mowed grass.

Ken McIntosh is the most prolific vintage tuner in New Zealand and an international authority on Norton Manxes. His business, McIntosh Racing Developments (01 1-64-9-5701119), caters to the preservation and racing of those timeless British Singles. McIntosh owns and cares for several race-ready Nortons, and I persuaded him to let me sample a few of them at Pukekohe.

He brought out six: a pair of ’62 Manxes belonging to customers; a ’51 “Featherbed” Manx; a ’48 “Garden Gate” Manx; a surprisingly rapid methanol-fueled ’37 International; and a rigid-framed ’27 Model 18 TT Replica. Competition for the bikes would be tight: A half-dozen riders besides me queued up to ride themMclntosh and Smart, CW Euro-scribe Alan Cathcart, former 125cc world champ Hugh Anderson, Reg Craig (son of former Norton technical director Joe Craig) and American Paul Adams, a former Pukekohe winner. With dozens of possible combinations of riders and bikes, McIntosh had to steal away to invent a chart showing who would ride which bike, and in which event. The task made his head hurt. When he got done figuring, he had slated me to ride five events on four bikes.

Although the later Manxes were fully booked for all races, I did get to ride one of the ’62s, built for McIntosh client Billy Apple, in practice. Like all Featherbed Manxes, the ’62’s handling is delightful. Light, low and precise, it affords absolute rider confidence-and serves as an excellent observation post. As luck had it, amiable Paul Smart was parading his 750 Ducati at the same time. I found him on the backstraight and tucked in behind the thundering Duck. With its high/low exhausts, the bike is unmistakable. Locked onto Smart’s megaphones, I got precisely the same view Smart’s old teammate, Bruno Spaggiari, had for most of the 1972 Imola event. Knees out, Smart neatly wheeled the long bike through the corners, crouched over the tank on the straights, and then casually sailed away. At 54, Smart is still graceful and fast.

Something else flashed into view that demonstrated the casualness of the Pukekohe weekend. It was event emcee John Hudson, quite naked, aboard his own Manx. As this practice session doubled as a Norton owners’ parade, the announcer had warned participants to wear boots and a helmet. Hudson took this literally. As he humped his Manx along the backstraight at over 100 mph, his loins positively flapped in the air blast. Riding to the rear, so to speak, I could not help but notice a surge in the interest

of the female spectators. Normally complacent race-watchers, they were now pressing close to the fence and waving Hudson on. Go, Johnny! At the start-finish line, the starter also waved-the black flag.

While North America spent the winter hunkering under El Niño rain, New Zealand was suffering from heat and drought. On Saturday the

temperature and humidity soared uncomfortably close to triple digits, boding poorly for the performance of man and machine. Races were limited to four laps in deference to the old machines, but riders had to sweat out two days of racing. The heat likely contributed to several crashes during the weekend. And, totally out of character, Cathcart went down on the ’37 Manx. According to witnesses, a heavy throttle hand got “Sir Alan” into a tank-slapper and waltzed him right into the Armco, breaking his lower leg in four places. Soon afterward, while leading his race, Paul Adams ran wide in the first hairpin, connected with the dragon’s teeth at the edge of the track and broke his collarbone. A former Navy jet jockey and an experienced racer, Adams accepted the incident good-naturedly, quoting a line from Little Fauss and Big Halsey: “I was riding as fast as I ever had,” he drawled. “Then I fell off.”

I hate going to ground, especially on borrowed machinery. So, prior to leaving for New Zealand, I had created a list of priorities in descending order of importance. Item 1) Do not fall down. Item 2) Have fun. Item 3) Go fast. Something in the philosophy must have worked, because I rode five races in two days, ran as high as second and finished between fourth and ninth in each race-slightly better than mid-pack. I might have done better if the rapid ’37 Manx hadn’t gotten bent, and if the ’51 Manx hadn’t been crippled by a fussy magneto. Of course, I might have been the fifth Beatle, too.

The casualties left me to contest two pre-war races on McIntosh’s splendid 1927 Model 18 replica. The bike isn’t fast enough to win the prewar class (although Smart won the vintage event on it). It also requires concentration; there is no positive gear stop, so you have to shift carefully. There also is no tachometer, so McIntosh rigged up a digital bicycle speedometer instead. The machine can hit 80 mph on Pukekohe’s backstraight, although Ken warned that over-revving it could scatter the top end. I limited myself to about 73 mph.

My pre-war races were carbon copies of one another. I drew a second-row grid position next to Len Perry. Here came the 5-second board, then the green flag. The cork clutch bit solidly and the old bike leapt forward with a surprising bit of wheelspin. I shifted to second and then top gear and found myself fifth into the first turn. The Norton tracked won> derfully on its modern-spec tires.

The backstraight proved a long road on a 73-mph racebike. But not for Perry and some others, who glided past and away on newer machines. I made back a few positions in the hairpin and esses on the second lap, lost them on the straights, and pretty much rode out the rest of the race in solitude, except for twice exchanging positions with the inexhaustible Perry. At the flag, I laid flat on the tank and watched him pull away. I finished the pre-war races in ninth and sixth. The ’37 could have won both.

I got one shot at a “real” Manx in Saturday’s event for pre-1963 factory racers. I refer to the ’51 as “real” because this bike competed in the 1951 Isle of Man TT in the hands of Rod Coleman, and because it has a Featherbed frame. That year, the Rex McCandless-designed Featherbed literally transformed the Manx into a predictable, stable racebike. And how delightful it is even today. The chassis arcs through bumpy sweepers with aplomb and is reassuring under heavy braking. No wonder the Featherbed inspired virtually every streetbike until perimeter frames arrived in the Eighties.

More than the ’27, the ’51 Manx seemed like a potentially competitive tool. But the magneto was behaving badly, and McIntosh suggested keeping the revs above 5000 to keep the engine happy. When my race was called, mechanic Bill Wallis pushed me down the warm-up lane, but I stalled once there and again on the pre-grid. Wallis was there to help and I made the grid just as the 30second board went up, wiggling into a second-row spot right behind McIntosh on his ’62 Manx. He’s a very good rider; with luck, I’d follow him into Turn 1.

The start went awry. I had intended to use lots of revs, but the ignition wouldn’t have it and the engine fell into a sputtering hole. In the agonizing second or two it took to slip the clutch, nearly 10 riders flew by, and I was mid-pack by the first turn. But I

picked up three places by Turn 3. The bike seemed to run okay on the backstraight, allowing me to slip by one rider. I passed two more on the final hairpin, but that’s all the progress I made; the fast guys were already gone. By lap three, the Norton began missing on the straight and a black Matchless G50 eased by. I re-passed under braking, but the 650 reclaimed the place on the front straight. Finally, he simply got away. I finished eighth, > contemplating what might have been. Hugh Anderson won and McIntosh finished second, each on a ’62 Manx.

The demise of the ’51 ’s magneto relegated me to the ’48 Garden Gate Manx for Sunday’s big-bore events. The ’48 was beautifully prepared, but its plunger frame has the approximate stability of Ted Kaczynski. A McIntosh-tuned engine and modern rubber make it even more virulent. I’d certainly lose time to the bike’s gyrations in the fast corners, so I hoped to get a great start, then try to hold on along the straights. It almost worked. In the graded scratch race, the bike jetted away wonderfully, delivering me to the first turn in third place. I swept into second by Turn 3 and launched onto the backstraight perhaps 30 feet behind the leader, eager to find out whether straightaways would favor us. They wouldn’t. Once again, riders on newer machines crept by. Late braking reclaimed a spot or two, but after three laps the ’48 felt alarmingly slinky in fast Turn 1-Rayborn’s corner. The results showed me seventh overall, fourth in class. At least I was still upright.

My final race was the all-Manx event which McIntosh won. Given the heat and various mishaps, I gave extra thought to my race plan, especially the start. I picked an inside grid position to avoid entering Turn 1 on the outside, and vowed to act prudently through the first three turns. The grid positively shook with the collective thrashing of nearly 20 Manxes. Big cranks swung inside their cases, external valve springs flailed, and the noise level rose and fell in asynchronous splendor as a castor haze swirled around us. I looked to my left, studying riders. There were old eyes in those helmets, the eyes of geriatric warriors still practicing their instinctive mission. I turned right. There was Len Perry, the oldest warrior. They seemed transfixed, all of them. It is the racer’s zone, regardless of age.

I got a fair start and was sixth to the first turn and fifth by the backstraight. I gave up the usual few places on the straights, gained back a few more under braking, and engaged in a terrific late-race battle with ’61 350 Manxmounted Kevin Grant. Although our lap times were identical, we each carried speed differently around the track. Grant’s advantage was the final sweeper, where he got a great drive, caught my draft and just nipped by for seventh place. Nary a spectator will remember it, but I’m sure we will.

The NZCMRR (P.O. Box 192, Takanini, Auckland, New Zealand) served an outstanding buffet meal at the track each night, followed by an awards banquet on Sunday. Many of the recipients, including Paul Smart, Hugh Anderson, Arthur Wheeler, Len Perry, Ginger Molloy and Ivan Rhodes, reflected on a bygone era of gentlemen racers. Afterwards, we Yanks-Paul Adams, Bob Sinclair and I-strolled the pits under a sky positively infested with exotic constellations, including the Southern Cross, and marveled at the wonderfulness of the Pukekohe experience.

We returned to the track the next morning to help McIntosh load bikes and to say our goodbyes. Here came 82-year-old Arthur Wheeler. “How’s that arm doing this morning?” he asked Adams, who is 58. Earlier in the weekend, Adams had opined that he might be getting too old for this racing business. Now in the presence of Wheeler, he seemed to reconsider. “Oh, it’s much better,” he grinned. “Us young guys heal real quick.” □