HIGH ROAD

ENFIELD BULLETS IN THE LAND OF MANY PASSES

MAC McDIARMID

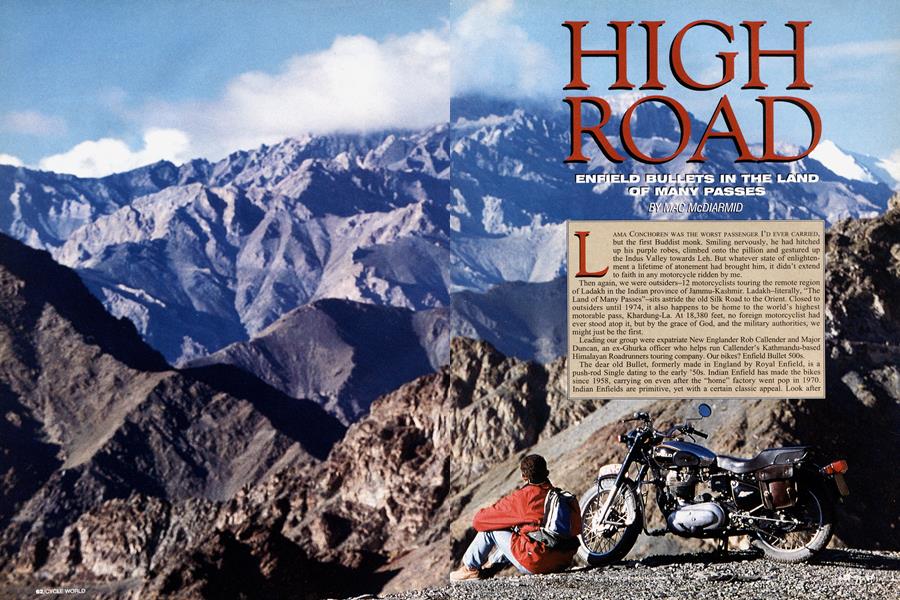

LAMA CONCHOREN WAS THE WORST PASSENGER I’D EVER CARRIED, but the first Buddist monk. Smiling nervously, he had hitched up his purple robes, climbed onto the pillion and gestured up the Indus Valley towards Leh. But whatever state of enlightenment a lifetime of atonement had brought him, it didn't extend to faith in any motorcycle ridden by me.

Then again, we were outsiders-! 2 motorcyclists touring the remote region of Ladakh in the Indian province of Jammu-Kashmir. Ladakh-literally, “The Land of Many Passes”-sits astride the old Silk Road to the Orient. Closed to outsiders until 1974, it also happens to be home to the world’s highest motorable pass, Khardung-La. At 18,380 feet, no foreign motorcyclist had ever stood atop it, but by the grace of God, and the military authorities, we might just be the first.

Leading our group were expatriate New Englander Rob Callender and Major Duncan, an ex-Ghurka officer who helps run Callender’s Kathmandu-based Himalayan Roadrunners touring company. Our bikes? Enfield Bullet 500s.

The dear old Bullet, formerly made in England by Royal Enfield, is a push-rod Single dating to the early ’50s. Indian Enfie!d has made the bikes since 1958, carrying on even after the “home” factory went pop in 1970. Indian Enfields are primitive, yet with a certain classic appeal. Look after her and the old girl’ll plod on forever, recreating those halcyon days when all a chap needed was a flat cap turned backwards and no pressing need to get anywhere quickly.

Our tour begins in Shimla, India’s old summer capital, where we undergo “machine familiarization.” For some in our party, it’s a first-time experience with a kickstart. From Shimla, we head north on a switchback road over razorbacked ridges. Verdant pinnacles rear out of misty valleys, their walls a riot of giant ferns and eucalyptus trees. At day’s end, we drop off the ridges to camp by the river at Mandi. Locals drop by to stare, as does a snake-charmer hoping to eam a few rupees. His cobras have no teeth. Neither, come to that, do the Enfield’s front brakes, seized near solid with a gunge of monsoon damp and asbestos dust. We strip and clean the lot.

From Mandi to Manali, we speed (relatively) through lowlands before wriggling past the Pandoh Dam and into the gorge of the Beas River. Memorable, but not as much as the sight of two seikhs riding scooters, one towing the other-by his turban!

Even if it weren't an implausible phenomenon, India’s trendiest ski resort at Manali would be bizarre. Cosmopolitan going on squalid, Manali is a cacophony of hippies, trekkers, donkeys, dope, dogs and teeming multi-racial humanity. We find peace in a Tibetan restaurant serving delicious “momo” (steamed meat dumplings) and potent local beer. The bill? Fifteen dollars for nine.

Our camp (as always, set up ahead by Rob’s gang) nestles in a grove of ancient cypress trees alongside a torrent of glacial melt. Soaring on three sides are snow-capped peaks and blue-ice glaciers. From here, four high passes bar the way to Leh, the capital of Ladakh, and to the pass at Khardung-La, our goal.

The Enfield thumps along under 1000-foot precipices and cascading waterfalls to the 13,051-foot summit of the first pass, Rohtang-La. Along the way are dozens of hand-painted signs, usually exhorting safer driving, but not always: “If you love her, divorce sheep,” urges one.

From Rohtang-La, the road plummets into the Chandra Khola Valley, and the first of many military checkpoints. Already there, rooting for their papers in the evening sun are Jerry and Arabella, two Edinburgh anthropology students. Their designer motocross gear amounts to woolly hats and sneakers. This is Jerry’s fourth-ever day on a motorcycle, a battered 350 Enfield of indeterminate color.

We head down the valley, then sharp right and up again. From time to time, we pass road gangs, black as coal, toiling over boiling pitch. Small knots of women supply chippings, sitting on their haunches laboriously smashing the Himalayas into plum-sized chunks. Ahead, at 16,046 feet, lies Baralache-La, the second of our five great passes. From Baralache-La, we descend to our next camp, a dried-up lake bed. At 13,800 feet, it is the highest and coldest so far.

The next pass, 16,634-foot Lachulung-La, begins with the Gata Loops, 21 vertiginous hairpins. Our reward comes at the summit, a hushed and breathless place, disturbed only by the rustle of prayer flags and the low moan of the wind from the plains.

We camp near Pang, next to a military camp. A pompous little man with captain’s regalia appears, telling us we can’t camp here. Kusiman, our exGhurka jeep driver, pointedly introduces Major Duncan, “of the British Army.” Sorry, the captain says, a mistake. Will the Major join him for dinner? The Major will. The Major, after all, has heard about Indian Army rum. Three hours later, he crawls back, retching.

Major Duncan notwithstanding, the next day we are still going strong. Jerry and Arabella are not: They pass us, south-bound, waving madly from the back of a battered truck, woolly hats intact, their Enfield dead by their sides.

Our next pass, at 17,582 feet, is Taglang-La. At the top is a windswept stone hut, a view across all Creation, and a sign-“Unbelievable, Is Not It?”~of doubtful syntax but indisputable truth. A torrent of hairpins leads down to a rocky valley, another camp, and Gya, with tiny terraced fields and neat stone houses, roofs waist-deep in winter hay. And everywhere, the bric-a-brac of Buddhist landscape: mani and chortens—prayer walls and shrines.

Between Gya and the Indus Valley is the Miru Gorge, a chasm cutting deep into the entrails of Ladakh. Knife-edge ridges of ocher, green and purple rise abruptly to a dragon-tooth skyline. At Upshi, the walls subside to a broad, barren valley, hemmed by mountains north and south. Dotted around it are bright green oases of settlement. Everything else is lifeless: a desert, two and onehalf miles in the sky.

We make for Hemis, across the pale, blinding wastes of the valley, before veering uphill across a plain of shattered stone. A mani wall and an avenue of giant chortens marks the final mile to Ladakh’s most celebrated gompa (monastery), set in an improbable cleft in the mountains. As we settle down in the guest compound, the local kids give us a rendition of, of all things, “Frere Jacques.” After sharing breakfast with a particularly intrusive donkey, it’s off to Tikse gompa, then Stok.

From Stok, we strike west down the Indus Valley, into a canyon from which there appears no way out. Then the road sweeps impossibly right, up a giddy ladder of hairpins to the rim of the gorge. At the head of the gorge, hovering halfway to the moon in an ash-grey landscape, is Lamayuru gompa. A mudwalled village nestles at its foot. If this isn’t the film set from The Man Who Would he King, it’s close.

A planned one-night stop at Lamayuru turns into two when the Ladakh Taxi Union calls a general strike for the next day. Venture onto the highway, we are warned, and you'll be stoned as scabs. Strike over, we head east, to Leh.

A cheerful confusion of shops and cafes, idealistic hippies and cynical street traders, Leh is a chance to clean up and shop. After two days R&R, news comes through that our application to climb Khardung-La has been approved. We set off early the next morning, accompanied by a policeman lest we decide to invade bordering Tibet.

From Leh to Khardung-La is 26.5 miles—25 across, and 1 */2 straight up. The road begins as lumpy bitumen, before degrading into mud and rubble for the final 10 miles. The Enfield grunts and puffs in the thin air, but makes it. The top, wreathed in clouds, is an anti-climax: gray, frost-shattered rock, dirty snow, the tattered rags of prayer flags, a rusty tin hut and possibly the highest outside privy on Earth. It’s not too unlike a garbage dump.

Then the clouds briefly part, revealing a tantalizing, otherworldly view to the north, over the Nubra Valley to the Karakoram Range. There is the Mustagh Tower, and somewhere beyond lies K2, second-highest peak in the world. It is simply, utterly, indescribable. Breathtaking, that’s the word. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter To Willie G., No.2

July 1995 By David Edwards -

Leaning

LeaningNorton Goes To Florida

July 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHeated Exchange

July 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupIndians, Yes, But Which Tribe?

July 1995 By Ion F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupNaked Honda Gets A Bikini

July 1995 By Yasushi Ichikawa