ROTARY REALITY

The English are at it again, this time with a rotary-engined Norton racer

Norton

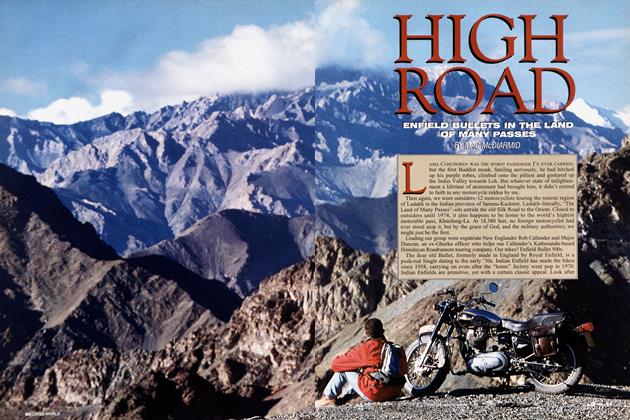

MAC McDIARMID

TWELVE YEARS AGO, ON AN OTHERWISE PLEASANT June day, I witnessed the death of Britain’s last real works racing effort.

The event was the Isle of Man TT, the place Glen Helen, the bike the Norton Cosworth. Rider Dave Croxford pulled into the marshall’s post, inspected the oil all over the rear of the bike, then discovered with disgust that the cause was a missing oil-filler cap. Typical! He propped the bike against one marshall, flung his helmet at another and stomped off to find solace in the bar.

We didn’t know it at the time, but the Cosworth’s racing future went with him. The bike never again turned a competitive wheel in works livery.

Since that time, we’ve seen numerous periodic notices of British-built bikes alleged to be “world beaters,” all of which turned out to be not so much premature as downright soporific fantasy. Paralleling this sorry jingoism has been the tale of the next Norton wonder engine, the Rotary: under-resourced, by many accounts an ill-conceived technical cul-de-sac, over 1 5 years in the making and still not in civilian use. And now, after all of this much-adoabout-nothing, Norton announces that it has built a Rotary Racer.

Excuse my cynicism, but would you expect Honda to take a 15-year-old streetbike—say, a single-cam CB750— put it up against state-of-the-art roadracers and stake the company’s reputation on it? I think not. But that’s exactly what Norton has done. And just to add a little zest to the venture—we Brits so like playing the underdog, after allNorton allowed itself a full six weeks from the drawing board to the track.

But I have to report that even real life can have fairy-tale endings. The Norton Rotary is, with one crucial proviso, the single most promising, most exciting machine to hit the tracks since Suzuki’s RG500 (which began life at much the same time but peaked a little earlier). And as far as technical novelty goes, it knocks anything of any age into a cocked hat..

I got a chance to ride the Rotary Racer at England’s Mallory Park Raceway, where it was introduced to the British motoring press. And the bike gives a very good first impression. It starts and picks up with surprising freedom: A short bump, a whiff of throttle and it rears away from you. I spent the rest of the day silently saying “Whoa.”

Norton race boss Brian Crighton estimates the engine’s output at 135 horsepower at 9200 rpm at the rotor shaft. That horsepower figure is not fiction, either. Opening the throttle coming out of Mallory’s Gerard’s corner—a long, long curve exited at around 100 mph—the rear slick digs in, the front wheel just barely patters over the bumps and the Norton relentlessly hurtles forward. There’s just time to grab top gear before you’re suddenly at the Esses and wondering who stole the back straight.

In the practice for the Rotary’s racing debut, rider Malcolm Heath reported that it left Britain’s best Superstockers (115-horsepower, street-based 750s) miles in arrears. Even more spectacularly, the Rotary rocketed out of Gerard’s behind a well-ridden RS500 Honda—all 128 horsepower and 280 pounds of it—pulled out of its slipstream and outdragged it into the Esses.

If the sheer power of the Norton is impressive, the manner of delivery is even more so. The Rotary pulls fiercely from as low as 4000 rpm and continues unabated well past the 9500-rpm redline. It delivers over 70 foot-pounds of torque all the way from 5000 to just above 10,000 rpm, with a peak of 79 foot-pounds at 8000 rpm. For comparison, the strongest Suzuki GSX-R1100 race engine ever dynoed in the U.K. peaked at 81 foot-pounds, but exceeded 70 only for about 3500 rpm.

Out on the track, this means that even Mallory’s tight hairpin corner is a second-gear affair. More crucially, it provides precisely the sort of urge off the line and out of corners that modern racing demands. A lap of the Mallory circuit required only four downshifts, and half of those were for the hairpin.

Because its flywheel effect and engine braking both are slight, the Rotary gains and loses revs quickly in a way that will be loved by hard riders. And no other race engine can possibly approach it for smoothness; I’d guess the lack of vibration will permit Norton to abbreviate the frame when weight-reduction becomes high on the agenda.

And the noise! If the Rotary grabs attention for simply being the new Norton, it assaults the eardrums for good measure. Everyone thought it reminded them of something, but no one could decide precisely what. Some said it recalled the howl of a works Triple, but they weren’t sure whether it was more like a Triumph four-stroke or a Kawasaki two-stroke. Others suggested a slightly silenced works Honda Six. One listener even said the Rotary sounded like an old Scott.

For the benefit of the hard-of-hearing, the Rotary even belches flames out of the exhaust, turbo-style, on the overrun. This is due mostly to the fact that the combustion chamber of a rotary is not stationary, but instead moves ever toward the exhaust port as the mixture bums, often sweeping its contents out into the exhaust system before the burning is complete.

There is one problem, however, a condition known as “light loading.” Rotary engines fire erratically at very small throttle openings—part of the reason why Suzuki’s RE-5 Rotary of the Seventies employed such elaborate carburetion. In the road engine this is overcome by what amounts to a fuel cut-off and pure air bleed, but such complexity was ruled out for the racer.

Had Norton officials wanted to hide this glitch from us, they’d have taken us somewhere with long straights and short turns. But Mallory, with its ultra-long, 200-degree Gerard’s curve and short straights, is bound to expose this light-loading condition at its worst. Riding the Rotary Racer through the first half of Gerrard’s—before you start to wind up for the back straight—was a thoroughly uncomfortable experience. The engine would hunt and peck in the manner of a two-stroke far too rich on the needle, with maybe a clapped transmission thrown in for giggles. Taking the bend in top rather than fourth allowed me to put a steadier load on the motor, but at the expense of a strong drive out.

In truth, the effect isn’t so abrupt as to threaten tire adhesion. It’s a discomfort rather than a serious speed handicap, but worth maybe a few tenths of a second per lap. A remedy—perhaps a change of ignition timing, or hot-air induction—isn’t very far away, but it’s not the highest priority at this stage.

Norton insists that its engine is still in a comparatively low state of tune, with only a few weeks’ earnest work behind it. Potential peak-power figures in the region of 160 bhp have been mentioned. Basically, the route to higher performance is the same as on a reciprocating engine: Cram more mixture in there and spin it ’round faster. But to hot-rod a rotary, even though it operates on familiar suck-squeeze-bang-swoosh principles, you have to forget almost everything you ever learned about four-strokes.

Crighton freely admits that the rotary has massive potential he hasn’t even begun to tap. But despite the welter of options open to him, even such a humble mod as a compression hike has scarcely been considered. He insists that the engine’s porting isn't at all radical —the inlet port is about the size of that in a hot 125cc two-stroke cylinder—and that the race powerplant differs little from the roadster’s. It’s arbitrarily redlined a mere 300 rpm higher, despite a conservative mechanical limit of 14,000 rpm. (The rotors fly apart at something over 1 8,000 rpm due to sheer centrifugal forces).

The main departure from standard is in induction plumbing; rotary engines need special provisions to cool the rotor core. The Norton road machine draws cooling air through the rotors and then into the carburetors. For the racer, Norton wanted a simpler and more powerful unrestricted cold-charge system. So the engineers came up with the old but little-used principle of exhaust-gas ejectors. This uses the kinetic energy of the exhaust gases to draw air, on the venturi principle, through ducting from the rotor cores. It's simple, light and provides air-flow proportional to engine speed and load. This also permitted forward-facing carburetors fed by a ram box.

Lightness the bike has in abundance. Already, with little attention to weight reduction and no exotic alloys (a few of the over-generous roadster mating surfaces and surrounding areas have been thinned), the complete bike weighs only 287 pounds. That compares to a claimed 340 pounds for the ultra-light works Suzuki endurance bike, albeit with lights and associated electrics. This surprised even Norton engineers, who, until they weighed the machine en route to the test session, had estimated something over 300 pounds. The powerplant and gearbox together scale a mere 1 1 8 pounds; a version with water-cooled rotor housings will be 20 pounds lighter still.

The engine is so much the focal point of this device that it’s unnecessary to dwell on the chassis. Norton was clearly dead-right to buy a tried-and-tested kit to enable the engineers to concentrate on the motor and transmission. The English frame-making company Spondon has a deserved reputation for building chassis that handle well for all manner of engine configurations, although the designers there did scratch their heads a bit at the funny-shaped Norton lump. The result, despite “inspired guesswork” as to weight distribution, shock-linkage ratios and the like, is on the right lines: flickable yet fairly stable, with its weight carried very low. It did feel a little stiff at the front, but on the other hand, it can’t be too far off if it tolerated the exit from Gerard’s.

Unfortunately, the motorcycling powers-that-be don’t really seem to understand the rotary engine. They understood it even less when they formulated the “2x” capacityequivalence formula back in the Seventies. This is the “crucial proviso” referred to earlier. Brian Crighton has no doubt that the Rotary is a four-stroke displacing 588cc, a topic on which he can give chapter and verse until next Christmas. But the FIM, the sport's governing body, says it displaces twice that, or 1 1 77cc. This is crucial, as there are comparatively few racing opportunities for the larger capacity. Norton is currently appealing the ruling—and perhaps wondering what the situation might be if the tank logo read “Honda” rather than “Norton.” Or perhaps how two-strokes might be rated if they were suddenly invented next Tuesday. In the car-racing world, incidentally, the equivalence factor recently came down from 2:1 to 1.7:1.

Not that there aren't advantages to novelty. “What’s the stroke?” asked a tech inspector preparing for a sound check.

“It doesn’t have one.”

“Oh, then what is the mean piston speed?”

“I told you, it doesn’t have any pistons.”

“Look, let’s pretend you’ve passed. Now, why don’t you just go away and leave me in peace?”

Norton's plans are to contest the remaining British SuperOne Championship rounds, plus some Battle of the Twins races, perhaps to hone the team’s skills in eligibility arguments. Along the way, the racer forms a testbed for a sports version of the stock roadster; the latter will be available this autumn. If a generous enough sponsor can be found, Norton plans to recruit a “name” rider to pitch alongside Malcolm Heath’s development skills and more modest track abilities. Endurance racing is under consideration, an arena in which an ultra-smooth engine that regularly handles 150 hours flat-out on the dyno could be especially favored. But most of all, the factory is “desperately keen” to add to its impressive but dusty tally of Isle of Man TT victories.

Next time, lads, I promise not to watch at Glen Helen.

Mac McDiarmid is a freelance jounalist living in England. Mike Nicks, Editor of Classic Bike magazine, contributed material for both Norton Rotary articles. 0

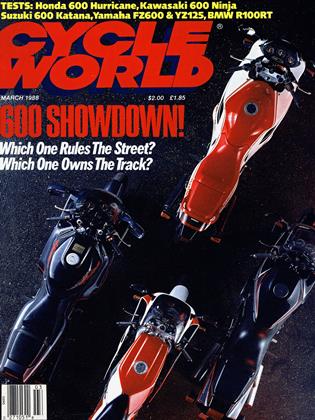

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

March 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

March 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1988 By Hector Cademartori -

Roundup

RoundupThe Perfect Motorcycle

March 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

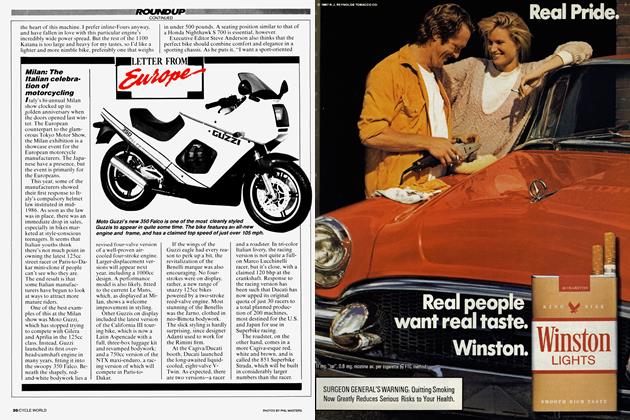

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

March 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

March 1988 By David Edwards