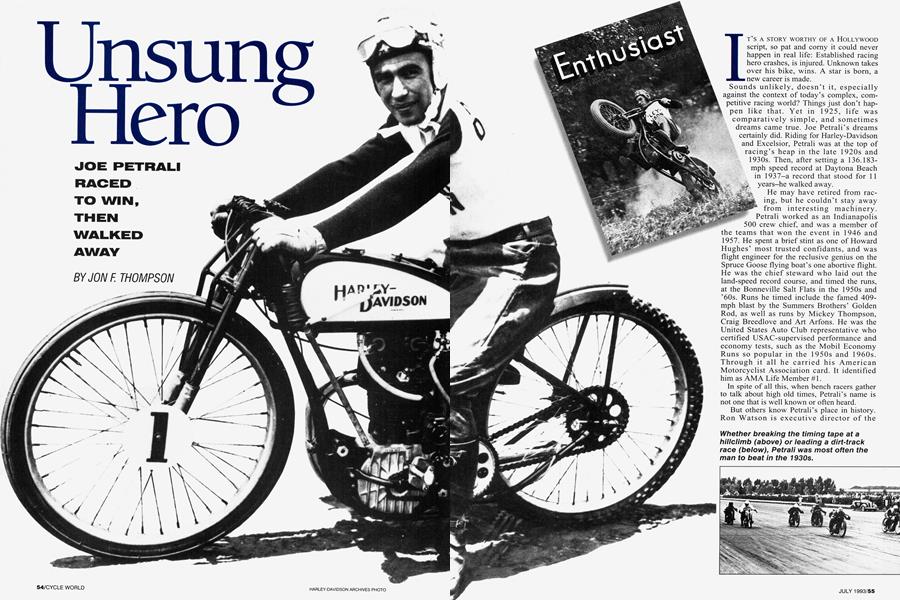

Unsung Hero

JOE PETRALI RACED TO WIN, THEN WALKED AWAY

JON F. THOMPSON

IT'S A STORY WORTHY OF A HOLLYWOOD script, so pat and corny it could never happen in real life: Established racing hero crashes, is injured. Unknown takes over his bike, wins. A star is born, a new career is made.

Sounds unlikely, doesn't it, especially against the context of today's complex, corn petitive racing world? Things just don't hap pen like that. Yet in 1925, life was comparatively simple, and sometimes dreams came true. Joe Petrali's dreams certainly did. Riding for Harley-Davidson and Excelsior, Petrali was at the top of racing's heap in the late 1920s and 1930s. Then, after setting a 136.183mph speed record at Daytona Beach in 1937-a record that stood for 11 years-he walked away.

He may have retired from rac ing, but he couldn t stay away from interesting machinery Petrali worked as an Indianapolis 500 crew chief, and was a member of the teams that won the event in 1946 and 1957. He spent a brief stint as one of Howard Hughes' most trusted confidants, and was flight engineer for the reclusive genius on the Spruce Goose flying boat's one abortive flight. He was the chief steward who laid out the land-speed record course, and timed the runs, at the Bonneville Salt Flats in the 1950s and `60s. Runs he timed include the famed 409mph blast by the Summers Brothers' Golden Rod, as well as runs by Mickey Thompson, Craig Breedlove and Art Arfons. He was the United States Auto Club representative who certified USAC-supervised performance and economy tests, such as the Mobil Economy Runs so popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Through it all he carried his American Motorcyclist Association card. It identified him as AMA Life Member #1.

In spite of all this, when bench racers gather to talk about high old times, Petrali's name is not one that is well known or often heard.

But others know Petrali's place in history. Ron Watson is executive director of the

Motorsports Hall of Fame, in Novi, Michigan, into which Petrali, who died 20 years ago, was recently inducted. Watson says of Petrali, “He was a pioneer in the sport, one whose record= stands up to anybody’s in the history of motorcycling.”

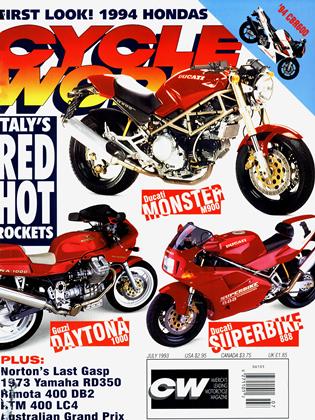

A complete tally of Petrali’s championships no longer exists, according to Watson. “But his national victories totaled nearly 70. He was national boardtrack champion in 1925, national dirt-track champion five times between 1931 and 1936, national hillclimb champion eight times between 1929 and 1938, and once had 31 consecutive hillclimb victories. The exact numbers just aren’t known,” says Watson. “Petrali didn’t dwell on his achievements. But he has to be considered with the very elite.”

It was in the 1920s that Petrali got his break. In those days a great many races were run on boardtracks, surfaced with 2x4 pine boards set on edge. Falling off then meant everything it still means today. Men shredded skin, broke bones, and sometimes died. But there was an additional peril. If you fell off while racing on a boardtrack, you very likely stumbled back to the pits with your hide full of pencilsized splinters.

It was exactly this fact of racing life that put Petrali in the winner’s circle and brought him to the attention of the Harley-Davidson factory. Jim Davis-now motorcycle racing’s elder statesman-was there, a factory star then teamed with the great Ralph Hepburn as a part of the HarleyDavidson Wrecking Crew. He remembers the incident clearly.

“It was July 4, 1925, at the Altoona, Pennsylvania, boardtrack. Hepburn fell off and got a splinter in his hand. Joe rode Hepburn’s machine and won the 100-mile event. It was really astonishing, something you never dreamed of, something you never thought would happen. From then on, the factory helped Joe, and he got going pretty good.”

But Petrali, the overnight sensation, had been struggling for years before this break, which saw him giving half his Altoona prize money to Hepburn as part of the deal that put him on the racebike. Davis remembers, “As a team, we split our money. It didn’t make no difference which one of us won, but one of us better be out front, because that’s where the money was.”

Dave Petrali, Joe’s son, worked with his father on land-speed record attempts and US AC product certifications from his high school graduation in 1960 to the time of the elder Petrali’s death in November, 1973. He

“Joe Petrali was a pioneer, one whose record stands up to anybody’s in motorcycling. He has to be considered with the very elite.”

says his father was born in San Francisco in 1904, and that his birth records were destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and subsequent fire. When Petrali went to work for Howard Hughes, he needed a birth certificate to receive a security clearance. He got one only after he tracked down the parish priest who had baptized him, Dave Petrali says.

Petrali’s racing career really began in Sacramento, where his family resettled after the San Francisco disaster. That’s where Davis remembers seeing him for the first time: “He was working for Archie Wright, the Indian dealer there. He was just a kid working in the repair department, washing off parts.”

Petrali’s interest in motorcycles began early. By the time he was 13, he had saved enough money to buy a 500cc Indian. In 1918, aboard his Indian, he won a local economy run by cruising 176 miles on the single gallon of gas issued each competitor. He was bit hard by the racing bug but too young to compete in sanctioned events, so for several years kicked around local outlaw events.

A break came in 1920, when he was offered a ride at Fresno, California’s steeply banked board speedway. He would ride an Indian sent there for Shrimp Bums, who had been killed in a racing accident the week prior. Along with Burns’ racebike, Petrali also got Jud Carriker, Indian’s west-coast race tuner. Carriker chose this event as his first heat-of-battle test of alcohol as a racing fuel. In practice, Petrali’s Indian ran fast enough to scare the HarleyDavidson team. To counter his threat during the race, the Harley team boxed Petrali in and wouldn’t let him pass. As laps reeled off and the race conclusion approached, Petrali used the Indian’s manual spark-timing lever to retard the ignition, then reached down as if to fiddle with the engine. The Harley riders, fooled into thinking he was having engine trouble, broke out of their box formation. Petrali advanced the spark and blew by all of the Harleys but one to take second place.

Real success continued to elude him, however, until he got his ride aboard Hepburn’s Harley-Davidson.

That ride not only began one of motorcycle racing’s legends, it also served as the foundation for a relationship between Petrali and the Davidson family.

Dave Petrali remembers,

“There was a special affection there, he genuinely respected the Davidsons. It was more than just endorsing their checks. He had a special relationship with those people. Those companies were all small enough that you got to know the proprietors. You knew who you were working for.”

But H-D went racing to sell motorcycles, and the Davidsons weren’t happy.

Davis remembers, “They figured that all the racing they’d done hadn’t helped their sales any. They won everything at Dodge City, yet the police there bought Indians. So they quit. When they quit, they take you off the payroll.”

That caused Petrali to turn to Excelsior, which, as Davis remembers, “in the early days, was just as good as Harley or Indian.” Excelsior, owned by Ignatz Schwinn, founder of the Schwinn Bicycle empire, was Petrali’s home from 1926 to 1930, and during that time he began his domination of the hillclimb scene.

His specialty was in unloading his Excelsiors-a 45-cubic-incher and the 61-inch machine he called “Big Bertha”-setting fast time in his first run in each class, and loading the bikes back up. In 1929, he won 31 consecutive hillclimb events without taking a second run.

“Maybe one of the reasons he quit when he did was that it just wasn’t worth the pounding anymore.”

Donald Davidson, USAC’s statistician and historian, recalls, “He was so good, but he wasn’t cocky about it. He was a very nice guy. They’d offer to give him another shot at the hill, and he’d say, ‘Nobody’s gonna top that.’ He was very matter-of-fact.”

Petrali’s son says, “He told me there were times you could run once and know you could never do better. One reason was that the hill would deteriorate after a number of runs. He didn’t always make it to the top of the hill. Remember, these hills were so steep you couldn’t walk up them. They had guys there with hooks and ropes to hook onto the bikes when they fell, to keep them from sliding back down to the bottom. Maybe one of the reasons he quit when he did, in addition to wanting to quit while he was on top, was that maybe it just wasn’t worth the pounding anymore.”

That may be the case, but Petrali took less pounding than many other racers of his time. He had just one truly heavy crash, bad enough that it almost killed him.

It happened in 1927, on a half-mile dirt-track in Springfield, Illinois. Jim Davis recalls it very well, though he

says, “The incident is one I don’t like to remember. I was his opponent in that race. It was a 15-mile race and I was on the pole. Joe was a hard rider. He was a gentleman, but he was a tough hombre to race with. On the third or fourth lap, he dropped down under me, but then broke loose and moved to my right. There was another rider there. They crashed and the other rider (Eddie Brinck) was killed. Joe was beat up pretty bad, too. I waved at them to shut the race off, but they made us ride the whole race,” which Davis won.

Dave Petrali says of the incident,

“He told me another rider had fallen in front of him and he had nowhere to go.” Petrali hit Brinck’s racebike so hard that the handlebar and steering head of his own machine bounced up and hit him in the face and upper chest, knocking him far into the air, breaking his jaw, nose and collarbone, and tearing away a piece of his lip, which was retrieved and brought to the hospital where Petrali was taken. His doctors were so certain that his injuries were fatal that they allowed an intern to practice his stitchery by repairing the damage to Petrali’s face. This included sewing the torn lip back into place. According to published reports, he was unconscious for 48 hours and hospitalized for eight weeks. Within 12 months, he was racing again.

In 1930, Ignatz Schwinn, beset by Depression-era financial problems, decided to concentrate on bicycles. He closed the Excelsior factory. By then, Harley-Davidson was back in racing, so all it took for Petrali to re-hitch his star to the Harley-Davidson steamroller was a single phone call. It was a fine marriage, one which brought Harley-Davidson some of its greatest racing success. But Petrali’s run was drawing to a close. In 1938, the year following Petrali’s much ballyhooed speed-record run at Daytona Beach, he retired from racing, perhaps at least in part because the factories had agreed to abandon the highly competitive and expensive Class A racing, which required purpose-built equipment, in favor of Class C racing aboard lightly modified production equipment.

“I always knew that I’d have to go and get him somewhere. He died doing what he enjoyed doing.”

Following that came his Indy 500 experiences, his stint with Hughes Aircraft, and his second career as a USAC and Bonneville performancecertification expert. He suffered a fatal heart attack while performing just such a role.

His son, Dave, remembers, “He died doing an economy run for Buick. I always knew I’d have to go and get him somewhere. He died doing what he enjoyed doing.”

In addition to his family, Petrali left behind other people who to this day remember him fondly, including USAC’s Davidson, who says, “He was a guy who helped shape the way Americans look at motorsport. He’d be legendary as a motorcycle racer even if he’d never done all the other things he did. And in spite of it all, he pretty much stayed in the background. He had the respect of everybody.”

Armando Magri, 78, says, “When I was a young racer, he was king of the hill, just almost unbeatable. He had as good a motorcycle as anyone, he had natural ability, and he had a lot of luck. When you’ve got those three things, you’re pretty hard to beat.”

Jim Davis, Petrali’s old Harley teammate, now 93 years old and still vibrant, agrees. He says, just a bit wistfully, “He was one of the toughest competitors. Joe rode hard everyplace, yet he was a clean rider. I wish he was still here.”