UP FRONT

Confessions of an aging street squid

David Edwards

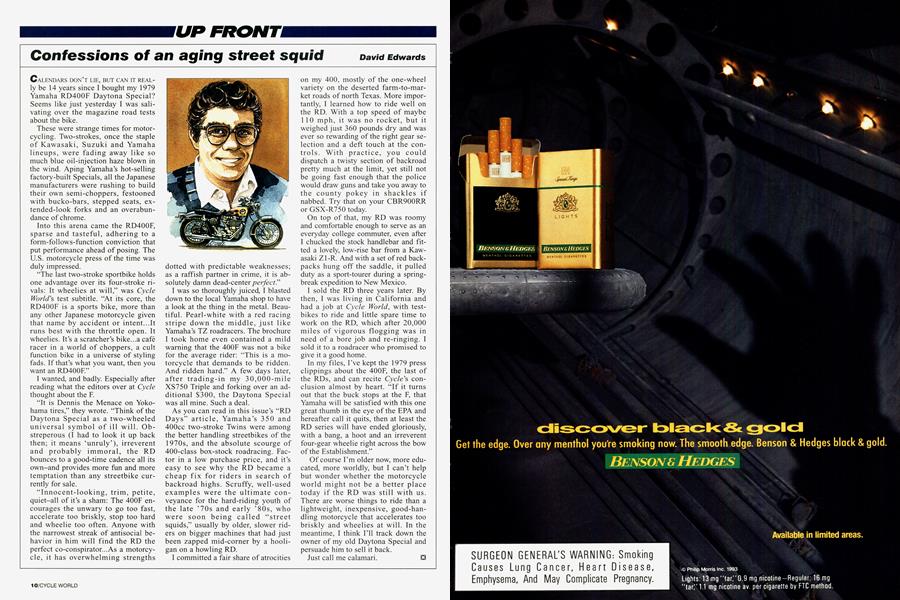

CALENDARS DON’T LIE, BUT CAN IT REALly be 14 years since I bought my 1979 Yamaha RD400F Daytona Special? Seems like just yesterday I was salivating over the magazine road tests about the bike.

These were strange times for motorcycling. Two-strokes, once the staple of Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha lineups, were fading away like so much blue oil-injection haze blown in the wind. Aping Yamaha’s hot-selling factory-built Specials, all the Japanese manufacturers were rushing to build their own semi-choppers, festooned with bucko-bars, stepped seats, extended-look forks and an overabundance of chrome.

Into this arena came the RD400F, sparse and tasteful, adhering to a form-follows-function conviction that put performance ahead of posing. The U.S. motorcycle press of the time was duly impressed.

“The last two-stroke sportbike holds one advantage over its four-stroke rivals: It wheelies at will,” was Cycle World's test subtitle. “At its core, the RD400F is a sports bike, more than any other Japanese motorcycle given that name by accident or intent...It runs best with the throttle open. It wheelies. It’s a scratcher’s bike...a café racer in a world of choppers, a cult function bike in a universe of styling fads. If that’s what you want, then you want an RD400F.”

I wanted, and badly. Especially after reading what the editors over at Cycle thought about the F.

“It is Dennis the Menace on Yokohama tires,” they wrote. “Think of the Daytona Special as a two-wheeled universal symbol of ill will. Obstreperous (I had to look it up back then; it means ‘unruly’), irreverent and probably immoral, the RD bounces to a good-time cadence all its own-and provides more fun and more temptation than any streetbike currently for sale.

“Innocent-looking, trim, petite, quiet-all of it’s a sham: The 400F encourages the unwary to go too fast, accelerate too briskly, stop too hard and wheelie too often. Anyone with the narrowest streak of antisocial behavior in him will find the RD the perfect co-conspirator...As a motorcycle, it has overwhelming strengths dotted with predictable weaknesses; as a raffish partner in crime, it is absolutely damn dead-center perfecti'

I was so thoroughly juiced, I blasted down to the local Yamaha shop to have a look at the thing in the metal. Beautiful. Pearl-white with a red racing stripe down the middle, just like Yamaha’s TZ roadracers. The brochure I took home even contained a mild warning that the 400F was not a bike for the average rider: “This is a motorcycle that demands to be ridden. And ridden hard.” A few days later, after trading-in my 30,000-mile XS750 Triple and forking over an additional $300, the Daytona Special was all mine. Such a deal.

As you can read in this issue’s “RD Days” article, Yamaha’s 350 and 400cc two-stroke Twins were among the better handling streetbikes of the 1970s, and the absolute scourge of 400-class box-stock roadracing. Factor in a low purchase price, and it’s easy to see why the RD became a cheap fix for riders in search of backroad highs. Scruffy, well-used examples were the ultimate conveyance for the hard-riding youth of the late ’70s and early ’80s, who were soon being called “street squids,” usually by older, slower riders on bigger machines that had just been zapped mid-corner by a hooligan on a howling RD.

I committed a fair share of atrocities on my 400, mostly of the one-wheel variety on the deserted farm-to-market roads of north Texas. More importantly, I learned how to ride well on the RD. With a top speed of maybe 1 10 mph, it was no rocket, but it weighed just 360 pounds dry and was ever so rewarding of the right gear selection and a deft touch at the controls. With practice, you could dispatch a twisty section of backroad pretty much at the limit, yet still not be going fast enough that the police would draw guns and take you away to the county pokey in shackles if nabbed. Try that on your CBR900RR or GSX-R750 today.

On top of that, my RD was roomy and comfortable enough to serve as an everyday college commuter, even after I chucked the stock handlebar and fitted a lovely, low-rise bar from a Kawasaki Z1 -R. And with a set of red backpacks hung off the saddle, it pulled duty as a sport-tourer during a springbreak expedition to New Mexico.

I sold the RD three years later. By then, I was living in California and had a job at Cycle World, with testbikes to ride and little spare time to work on the RD, which after 20,000 miles of vigorous flogging was in need of a bore job and re-ringing. I sold it to a roadracer who promised to give it a good home.

In my files, I’ve kept the 1979 press clippings about the 400F, the last of the RDs, and can recite Cycle's conclusion almost by heart. “If it turns out that the buck stops at the F, that Yamaha will be satisfied with this one great thumb in the eye of the EPA and hereafter call it quits, then at least the RD series will have ended gloriously, with a bang, a hoot and an irreverent four-gear wheelie right across the bow of the Establishment.”

Of course I’m older now, more educated, more worldly, but I can’t help but wonder whether the motorcycle world might not be a better place today if the RD was still with us. There are worse things to ride than a lightweight, inexpensive, good-handling motorcycle that accelerates too briskly and wheelies at will. In the meantime, I think I’ll track down the owner of my old Daytona Special and persuade him to sell it back.

Just call me calamari. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue