GRAND PRIX 1993

RACE WATCH

OBSERVATIONS AND ANALYSIS FROM THE FIRST GP OF THE YEAR

Kevin Cameron

ONE RACE DOES NOT A SEASON MAKE. BUT IF THIS year’s 500cc GP opener at Eastern Creek, Australia, is any indication, 1993 will be a year of technological drama in the quest for the world roadracing championship.

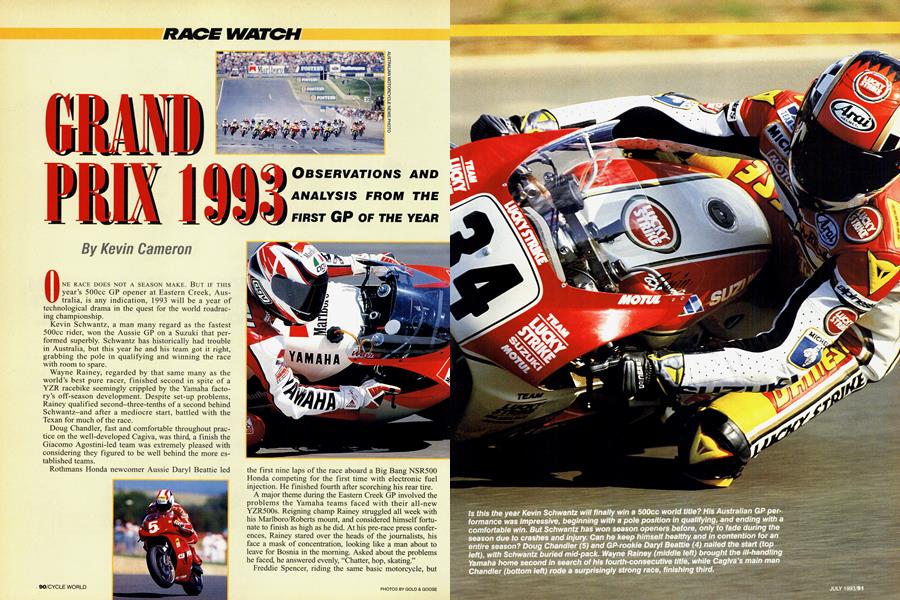

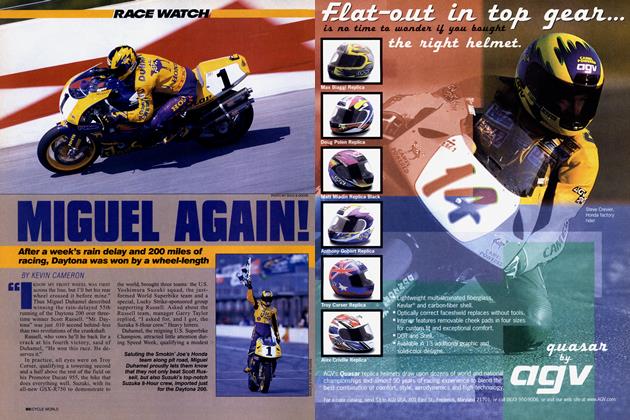

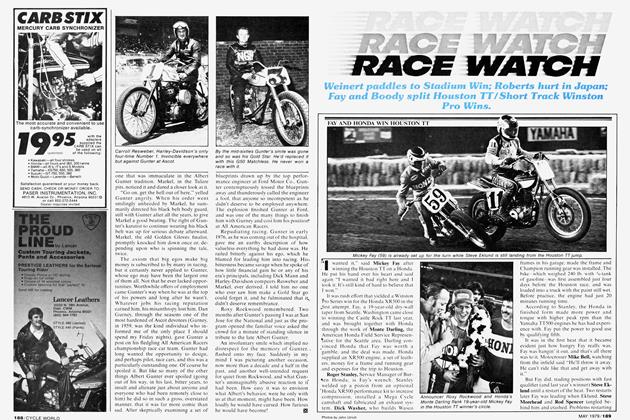

Kevin Schwantz, a man many regard as the fastest 500cc rider, won the Aussie GP on a Suzuki that performed superbly. Schwantz has historically had trouble in Australia, but this year he and his team got it right, grabbing the pole in qualifying and winning the race with room to spare.

Wayne Rainey, regarded by that same many as the world’s best pure racer, finished second in spite of a YZR racebike seemingly crippled by the Yamaha factory’s off-season development. Despite set-up problems, Rainey qualified second-three-tenths of a second behind Schwantz-and after a mediocre start, battled with the Texan for much of the race.

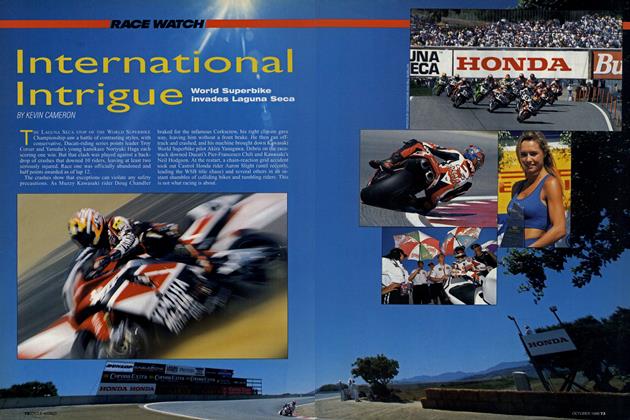

Doug Chandler, fast and comfortable throughout practice on the well-developed Cagiva, was third, a finish the Giacomo Agostini-led team was extremely pleased with considering they figured to be well behind the more established teams.

Rothmans Honda newcomer Aussie Daryl Beattie led

the first nine laps of the race aboard a Big Bang NSR500 Honda competing for the first time with electronic fuel injection. He finished fourth after scorching his rear tire.

A major theme during the Eastern Creek GP involved the problems the Yamaha teams faced with their all-new YZR500s. Reigning champ Rainey struggled all week with his Marlboro/Roberts mount, and considered himself fortunate to finish as high as he did. At his pre-race press conferences, Rainey stared over the heads of the journalists, his face a mask of concentration, looking like a man about to leave for Bosnia in the morning. Asked about the problems he faced, he answered evenly, “Chatter, hop, skating.”

Freddie Spencer, riding the same basic motorcycle, but for the Yamaha France team, was similarly puzzled. “The back end comes around when I’m going in. We’re having to do the opposite of what I’ve done all my life. We’re raising the front, trying to put some weight on the back,” he said.

How did Yamaha, winner of the last three 500cc world championships, find itself in this predicament?

First, conventional wisdom says that tire grip and engine power generally improve from year to year. That being the case, engineers could expect that a current machine, combined with next year’s engine and tires, would accelerate harder off corners, thereby lifting weight off its front wheel and running wide, or “pushing.” Therefore, next year’s bike should probably anticipate this problem by having its weight shifted slightly forward.

Designers expected tire grip to increase, because it always has, so Yamaha moved weight forward for 1993. Designers expected a stiffer chassis to perform better, because stiffer has traditionally been better. Quicker response was deemed appropriate, so Yamaha stiffened the chassis. Designers expected higher performance from firmer suspension rates that could be used along with the stiffened chassis. It had worked in the past, so they did it again.

The expectations turned out to be wrong. Tire grip did not increase. The stiffer chassis became a “controlled disaster” for unforeseen reasons. Projected weight distribution turned out all wrong, higher spring rates likewise. But these directions have been right for years; what could possibly have reversed them?

Let’s take these things in order. Tires first. Tire makers have been heavily criticized for doing their job: providing grip. The trouble is, the higher the grip, the more sudden is the release when grip is finally broken, so the usefulness of super grip was reduced by riders’ inability to sense its limits.

If engineers anticipated more grip, but actually received the same, their increased forward weight bias would fail because there would be too little load on the rear tire; the “coming around” symptoms found by Spencer would result. Further, now with slightly less grip, the bike would load its suspension slightly less in turns. Suspension rates equal to last year’s, or slightly harder, would thus be too > hard-possibly causing chatter and hop.

Now the stiffer chassis. At modern cornering angles, a GP bike’s suspension is nearly at right angles to the bumps it’s designed to absorb. The suspension-already very firm to carry a GP bike’s heavy-duty cornering loads-would have to rise more than two inches to completely absorb a oneinch bump at full lean angle. Thus, the motorcycle’s suspension is progressively losing its value in corners.

What, then, deals with bumps when the bike is leaned over? The answer is the tire and chassis, whose flex becomes the functional, in-corner suspension system of a GP bike. Tiny bumps of high frequency are absorbed by the tires, and middle-sized bumps have been taken up by lateral bending of the front fork, slight twisting of the steering head and lateral parallelogram-bending of the swingarm. Larger bumps are passed along to the suspension itself.

Now, it’s clear that by making its fork and chassis stiffer for 1993 (for reasons that had in the past been very good ones), Yamaha reduced its ability to absorb mid-sized bumps. These were then passed along to the suspension, which was unable to cope with them. The result, as Rainey so succinctly put it, was “chatter, hop, skating.”

And now for the trend that went unconsidered: the shift to the close-firing-order, Big Bang engine. You can see and hear the difference in machine behavior immediately. In the past, hard off-corner acceleration was a slip-and-grip affair, with violent changes in engine note, and with the machine sliding, catching and wobbling. But with the Big Bang engine blurring the difference between gripping and slipping, the rider can apply throttle sooner, and can slide the back end smoothly, without violent releases and hook-ups.

All this new smoothness equates to less need for absolute chassis rigidity. Because rear tires driven by Big Bangers no longer hook up suddenly, the old impulsive loads, tending to lift the front wheel, exist no more; there is therefore less need for extreme forward weight distribution.

Confusion between performance and control could have been the culprit here. A vehicle can have high performance and yet be hard to control. It often happens that a lower-performance design with higher controllability gives faster lap times. The 1988-90 500s had high performance, but their poor controllability made that performance impossible to use fully.

So what does this mean today? Riders testing Big Bang prototypes talk about higher performance, as though they accelerate harder, but, in fact, what Big Bang delivers is more control. Riding a Big Banger, the rider laps faster because he can safely use the available acceleration more of the time. But it’s easy to interpret the results to mean that the rate of acceleration-the performance-is higher.

The engineers expected higher performance, and revised the chassis to cope with it. Instead, Big Bang delivered higher controllability, and that made their revisions incorrect. The engineers were like generals who prepared for a frontal attack that never came, and thereby made themselves vulnerable to one from the rear.

The Yamaha factory promised a new chassis for the Japanese GP, three weeks after Australia, so the team went to the next event, Malaysia, with what they had. In Australia, the team wished they had the 1991 chassis, the one on which Rainey had set many of his fastest times. That was at the peak of the “engine controls” era, when the worst violence of the ’88-90 engines had been tamed by traction-control technologies, before the Big Bang changed the nature of rear-tire traction.

Unlike Yamaha, Suzuki did things right in the off-season. Lead rider Schwantz is reportedly in the best shape of his life. The bike is equally ready this year. Schwantz could approach a corner, toss his bike over in his casually flamboyant style, and then rail around the inside, leaving himself the entire width of the track at the exit for hard acceleration. It was brilliant to watch. No one else could hold line with him. And in contrast with recent years, the Lucky Strike Suzuki now has both competitive acceleration and top speed. As usual, the Hondas posted the fastest top speeds, at 182 mph, though the Suzukis were right there, at 180 mph. The Yamahas and Cagivas came in at 178 and 177, respectively.

In past seasons, Schwantz has had to find in himself whatever might be lacking in the machine-a dangerous way to race. Occasionally, the strain of this strategy has showed, but mostly Schwantz preserved his off-hand, letshave-fun manner. Asked what is different this year, he replied, “Stu Shenton.”

Stuart Shenton, son of Stan Shenton who managed the Kawasaki U.K. team in the ’70s, came to Suzuki last season from Honda. His experience has evidently made a big difference this year to a team badly in need of integration.

Doug Chandler said he thought the turning ability of his Cagiva was “at least equal to Yamaha’s,” and that’s how it looked. He was one of the riders you would have chosen for the top five with your eyes shut-just from the sharpness of his throttle-tobrake transitions, and from the degree of sliding he was using off corners. The bikes seemed very quick and agile, while Chandler very definitely seemed ready.

Honda created the Big Bang concept in 1992, and Mick Doohan used it to amass a huge, 52-point lead before his injury and flawed convalescence helped Rainey to the crown. This year, Honda has finally committed its fuelinjection system to competition; both Doohan’s and Beattie’s bikes were soequipped, though crew members refused to confirm or deny the injection system’s use. The giveaway? Thermocouples in the fat part of the NSR’s exhaust pipes. Carburetors give an engine what it “asks for,” but mapped fuel injection must “know” many variables in order to supply a correct mixture. One of these is pipe temperature:

A cool pipe makes the engine rev lower, a hot pipe makes it rev higher. The injection computer has to know which it is, and thermocouples supply that information.

In action, the injection system’s benefit is dramatic. A short pushstart, and the engine catches and runs without fuss at a steady 3800 revs, not needing the typical frenetic throttle-snapping to keep it running. When the system has been serviced, which leaves its fuel lines dry, it must be pushed a couple of hundred feet to prime it; evidently the pump is mechanical rather than electric.

As with other recent NSRs, this engine has a jackshaft (with balancer weights to reduce the otherwise heavy shaking of the close-firingorder engine) that turns “backwards.” When the throttle is blipped, the bike tilts forward in torque reaction.

Eastern Creek, with a moderate lap average of 96 mph, qualifies as a tight, turn-accelerate-and-brake race course. The corners here are interconnected; botch one and you’ve botched the next two. There is a lot of combined accelerating (or braking) and directionchanging. Slower riders prefer to separate the functions: brake on the straight, then roll over, not both together. When the combined maneuvers are pushed, instability comes through. When braking or accelerating hard, most of the weight is on one wheel, so the damping effect of the other tire is lost, and the bike instantly rewards its

rider with a weave. Rainey, Schwantz and Chandler are masters at making this all look slick, and they compress the maneuvers into far less space than is taken by the journeymen.

The race itself was a dazzler, though the probable outcome was already evident from practice. Other things being equal, Schwantz would win, for he clearly had the combination. The Hondas were fast, but master pilot Mick Doohan was slowed by a wrist injury suffered in pre-season testing-that in addition to his imperfectly healed hurts from 1992.

Nevertheless, Doohan would set fifth-fastest time in the race before retiring on two cylinders. Beattie, although he led the race on the second Honda, hadn’t yet the craft to lead and simultaneously give necessary comfort to his tires, which eventually faded. Chandler is a technical master who goes as fast as his knowledge permits, but would rather not gamble or guess. Rainey rides with a fierce, scary intensity that never suggests loss of control, but which leaves the watcher sure that winning champi> onships is a very urgent matter for him-not a sport, not a game.

It all came down to Schwantz, Rainey and Chandler, fighting most of the way. Schwantz pulled a small gap at the halfway point, though a slight rain allowed Rainey and Chandler to catch up. Schwäntz and the Suzuki had a little extra, however, and the race was theirs.

What remains to be seen in coming races is if the mercurial Schwantz can string together an injury-free season; if Doohan can regain his world-beating form; if Chandler can give underdog Cagiva more podium positions; and if Rainey can get the needed speed out of his new and (so far) unimproved Yamaha to win his fourth-straight title. It will be an interesting year.