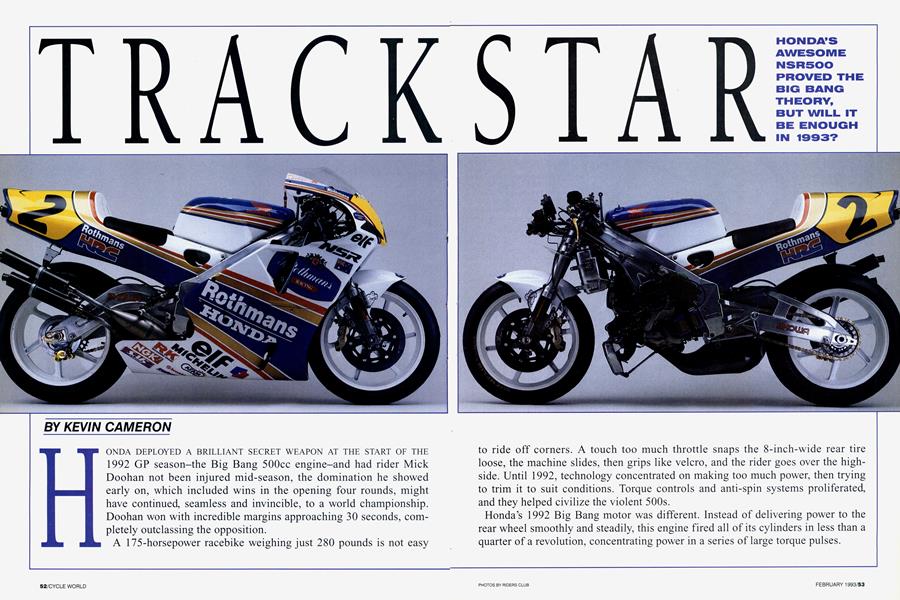

TRACK STAR

BY KEVIN CAMERON

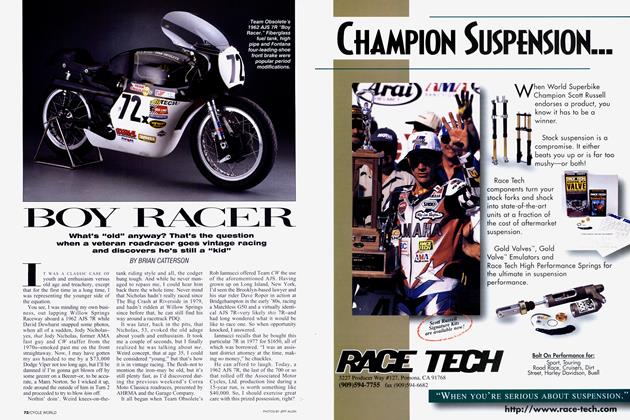

HONDA DEPLOYED A BRILLIANT SECRET WEAPON AT THE START OF THE 1992 GP season-the Big Bang 500cc engine-and had rider Mick Doohan not been injured mid-season, the domination he showed early on, which included wins in the opening four rounds, might have continued, seamless and invincible, to a world championship. Doohan won with incredible margins approaching 30 seconds, completely outclassing the opposition.

A 175-horsepower racebike weighing just 280 pounds is not easy to ride off corners. A touch too much throttle snaps the 8-inch-wide rear tire loose, the machine slides, then grips like velcro, and the rider goes over the highside. Until 1992, technology concentrated on making too much power, then trying to trim it to suit conditions. Torque controls and anti-spin systems proliferated, and they helped civilize the violent 500s.

HONDA’S AWESOME NSR500 PROVED THE BIG BANG THEORY, BUT WILL IT BE ENOUGH IN 1993?

Honda’s 1992 Big Bang motor was different. Instead of delivering power to the rear wheel smoothly and steadily, this engine fired all of its cylinders in less than a quarter of a revolution, concentrating power in a series of large torque pulses.

It’s not easy to make a wide, gummy rear slick slide controllably. It tends either to stick solidly, or let go altogether. One time-honored system is to apply a sharp tap on the back brake. Another is to make a purposely hard upshift. Either way, the rider is breaking the tire loose by means of a torque pulse that momentarily overcomes the tire’s solid grip, inducing a slide. The Big Bang motor’s big torque pulses make it possible to smoothly and predictably break that big back tire loose. In effect, a Big Banger divides the former slip-and-grip cycle into tiny pieces, blurring the formerly treacherous transition from gripping to sliding. Once the rider knows he can do this, he is able to ride much closer to the limit of traction. Gone is the sudden release, grab and highside.

Industrial analysts will tell you that this breakthrough is most un-Japanese. Japanese engineering usually achieves its greatest successes incrementally, making many small improvements that, taken together, raise a product to great heights of quality and function. In contrast, Honda’s development of the NSR500 has oscillated between incrementalism and wild, innovative gambling.

Even the origin of the first NSR concept was personal, idiosyncratic, fraught with risk-not a matter of committee decisions. Honda Racing Corporation Engineer Kazuhiko Miyakoshi believed an engine should have the minimum of parts, and Honda’s first GP-winning two-stroke, the 1982 three-cylinder NS-3, was a total break with GP orthodoxy. Instead of the twin cranks of the Suzukis and Yamahas, it had one. Instead of their eight main bearings, it had four, with no jackshaft. In place of the opposition’s complex rotary intake valves, the little NS had stone-simple reeds. The success of Miyakoshi’s Triple was assured not by horsepower (it began with 108 to the rivals’ 135 or more), but by its accidental perfect suitability to the riding style of one Freddie Spencer. No other rider could have been world champion on this machine.

Spencer won the 1983 500cc title on the novel Honda Triple, but he and tuner Erv Kanemoto knew it couldn’t happen again. They needed the legal FIM maximum of cylinders-four-and the higher revs and power that would come with them. The company granted this wish, but in its own style, with another

single-crank, reed-valve Vee-design-the first NSR500. Was this bike a simple power-up from the Triple? It was not. Instead, Honda gambled again on a radical concept, carrying the heavy fuel beneath the bike, routing the lighter pipes over the top. Engineers expected quicker handling to result from this lowering of the machine’s center of mass.

To assist rapid direction-changing and acceleration, the NSR was given a very light crank. Yamaha had tried this a year earlier, but when the rear tire broke traction, the light flywheels allowed the engine to rev off the tach before the rider could catch it. The NSR accelerated well, but was slow in direction-changing, no faster than the Triple in top speed, and heavy. When a motorcycle flicks over for a turn, it doesn’t pivot on its tire contacts, as intuition suggests, but rather around the combined center of mass of rider and machine-a line that is some two feet or more above the ground. To steer left, the wheels are countersteered to the right, while the upper part of machine and rider fall to the left, all rotating around this mass centerline.

By putting the gas on the bottom, Honda had actually moved it away from the true roll axis, making the machine harder to flick. In later testing, when ballasted to resemble the Triple, with the fuel weight above the engine, the NSR was equally agile. While Honda was figuring all this out, Eddie Lawson took the 1984 title for Yamaha.

The next year brought change. The radicalism of the underslung fuel tank was swept away, and the transitional multi-tube chassis and swingarm of the ’84 model were replaced with stiffer twin-beam structures, adopting Antonio Cobas’ concept. As power rose and rear-tire grip improved, there was less load on the front wheel to make it steer off of comers. The engine would be repeatedly moved forward to compensate, crowding the radiator into the now-familiar curved shape.

Yamaha’s twin, contra-rotating cranks offered no gyro resistance to rapid direction-changing. To turn with the agile Yamaha, the Honda, with its single crank’s sizable gyro effect, had to be given very steep steering geometry. The result? Compromise; the Honda’s turning was improved, but stability deteriorated.

Spencer was able to win the 500cc title with apparent ease, but the season had been a consuming effort. A variety of troubles had entered Spencer’s life, troubles that would put him out of GP racing.

The 1986 bike was developed for Spencer, incorporating his taste in powerband and handling, but the main riding task would, in Spencer’s frequent absence, fall to Wayne Gardner. Trained on large production bikes,

Gardner needed a fourstroke powerband, less forward weight bias and more chassis stability. Not finding them in the NSR, Gardner developed an athletic, defensive style, accepting the machine’s slip-and-grip, weaving acceleration, and trying to ride it out. He broke a lot of windscreens in his game efforts to stay on, but the title went again to Lawson and his Yamaha.

The 1987 machine was redesigned for Gardner. Engine rotation was reversed by a torque reaction to long jackshaft, so that its acceleration pushed down, rather than lifted, the front wheel. Reverse rotation also allowed wheel rotation to cancel some crank gyro effect. The ’84-’86 engine had carried its carbs on top. The upper cylinders took their charge directly, but charge for the lower pair flowed through the flywheel separations, producing a power loss. Now the carbs (two double-bodied, round-slide Keihin specials) were moved into the widened Vee at the front of the engine.

The natural powerband given by a two-stroke exhaust pipe isn’t wide enough or smooth enough for use on a 500. Honda had used a variable-pipe-volume system called ATAC, to broaden its power, while Yamaha had used a variable-exhaust-port-height system called YPVS. Honda engineers were now persuaded that an exhaust gate like Yamaha’s had advantages, so a special type (some call it a “drawbridge”) was developed to suit the divided exhaust ports of the Honda.

With this improved machine, and through his own absolute determination, Gardner overrode the Honda’s still evident handling troubles to become 500cc world champion in 1987.

Over the years, Honda has usually maintained a horsepower edge on the competition-useful on fast tracks, but often a handicap elsewhere. For 1988, new engine castings were prepared, making the result narrower and more compact, with power now in the 160 range. But HRC Engineer Shinichi Tsunoda sought to improve steering response by lowering the entire chassis, putting the unbraced aluminum-beam swingarm horizontal, rather than drooping from front to back as on most machines. Consequently, the Honda now squatted under power, producing unwanted attitude changes in comers.

People involved in 500cc racing were now desperate for anything that might tame the handling troubles all were facing. Some university researchers using math models were claiming chassis were too stiff, so Yamaha had actually tried cutting out chassis cross-members and hanging engines from intentionally flexible plates. Applied to the 1988 NSR, this concept was an unqualified disaster.

A more promising idea was to use electronic controls to limit or smooth engine power, to permit upset-free drives off comers. HRC engineers developed a system that tied exhaust-gate height to throttle angle; at low throttle, the exhaust ports would close down, preventing charge loss and giving the engine the ability to fire on much lower throttle. Acceleration was slowed somewhat, but harsh throttle transition was eased.

Problems arose elsewhere. Lightness mania infected the brakes, but the lighter the rotors, the hotter they get, and at some point, warping and fade begin. Honda engineers sought ways around this, fiddling endlessly with brake details that promised to permit ultra-light rotors to survive. The result was brake failure. The NSR program now seemed like many corporate departments, each highly competent, but lacking in overall integration. The resulting 1988 bike was exhausting even to watch, much less to ride.

Now the nemesis, Eddie Lawson himself, joined Honda to ride the Rothmans/Kanemoto NSR500 for 1989. Lawson looked forward to using the “Honda lanes” at faster circuits-his way of describing the superior top speed of the NSR. He found the handling deficient, and also rejected the low-mass crank, which made acceleration treacherous. Unlike Gardner, who had tried to adapt to the machine, Lawson would bring what was needed to the NSR program: informed, constructive criticism. Ultimately, it must be riders who make critical design judgments, but not all riders know what they want. Great racebikes are always designed with the cooperation of a great rider-never in a vacuum of pure, white-room engineering.

1989 was to be a season of hard and effective work. Now finally rejecting the “tuned flex” chassis idea, the Honda engineers set about a year-long odyssey of building up chassis stiffness. First came the new Showa inverted fork, nearly 50 percent stiffer than what it replaced. Next came welded, integral forward engine mounts to replace the former flex plates so the engine again contributed to chassis stiffness. For the super-fast German Hockenheim round, Lawson received a chassis whose main side beams had been doubled in section, with a sheeted-in swingarm that looked like an aluminum pup tent.

All this stiffness had the effect of shortening the period of weaveupset that followed every sudden excursion of the rear tire, allowing Lawson to get on the throttle harder and sooner.

But it remained impossible for the single-crank Honda to change direction with the Yamaha. In an effort to ease this, small 16-inch front wheels (sometimes in carbon material) and tires were brought back. Despite these efforts, the machine remained what Lawson called “the ponderous Honda.” Kenny Roberts expressed the view that Honda would not get any single-crank-engined bike to handle satisfactorily.

Heavier crank flywheels helped Lawson adapt to the Honda’s violent acceleration early in the season, but with the engine coming under better control, lighter cranks could again be used, restoring some of the Honda’s famous top-end acceleration advantage. Ventilated iron brake rotors solved many problems, and eased transition to the coming era of satisfactory carbon brakes. Lawson and Kanemoto tested relentlessly, keeping up a development pace and quality of riding impossible to match. Honda and Michelin backed this with equal efforts of their own. The title was theirs.

At the end of 1989, HRC’s Tsunoda revealed that Honda had indeed built and tested a contra-crank 500cc engine. Performance was good, but this machine would not be used. Why? There is more of culture or politics than of engineering in this decision. Miyakoshi’s low-friction, single-crank concept had become enshrined as Honda’s Way, while the twin contra-crank idea had become The Enemy’s Way. Although each GP team has liberally copied the others where necessary, Honda stuck to its own Way on the crankshaft.

As a harbinger of future direction, Honda now tested an engine timed to fire pairs of cylinders at 180-degree intervals, rather than one cylinder every 90 degrees. A likely reason for this was the length and consequent torsional flexibility of the NSR’s crank as peak revs began to exceed 13,000. Two big torque pulses deliver half the excitation frequency of four smaller ones-important for crank survival at high revs.

For the 1990 season, Honda deployed all it had learned about engine torque control. The violent, weaving comer exits of 1988 were all but banished now. Besides the 180 firing order, throttle/exhaust gate coupling, torque limitation in lower gears and outright anti-spin technology, using front and rear wheel-speed sensors, appeared on the operational NSR. ATAC was back, too, now combined with the exhaust gate to further tailor power delivery. Australian rider Mick Doohan might not be able to turn with the Yamahas, but his corner exits were now rocketlike and smooth.

The NSR was revised in detail to make it easier to service, resulting in the almost “bare” look it has to this day. Attention was given to internal airflow-the efficient entry and exit of radiator cooling air and the provision of fresh, unheated outside air to the carburetors. Honda GP motorcycles now embodied jewel-like quality of execution in every part. Beautiful detailing abounded, such as a needlebearing-equipped roller at the tip of the front-brake lever, where it bears against the master-cylinder piston, or the forged-aluminum foot controls, also pivoting on sealed rolling-element bearings.

Despite great effort, Honda could extract only three wins in 1990. Yamaha’s resources were now concentrated behind the Marlboro/Roberts team, wellequipped with veteran tuning specialists of all kinds. Honda, by contrast, appeared to treat racing as a normal corporate branch, subject to the usual frequent changes of personnel-and policy. Those who have worked in the aerospace industry know the situation well.

Although our usual image of Japanese corporate life is of a likeminded group seeking harmonious consensus, Honda often acts in a more Western, risk-taking and competitive way-surely traceable to the powerful personality of Soichiro Honda himself, who was never afraid of new ideas, or of failure. Doohan won three GPs on the refined NSR in 1991, a tremendous accomplishment and enough for second place in the 500cc championship behind Wayne Rainey’s YZR500, but desperate pressure had by now built up within Honda over the continuing failure to overcome the Yamaha. Even Suzuki-a latecomer to racing V-Fours-was winning more races than Honda.

Then Soichiro Honda himself reached the end of a long life, leaving the company with only his memory and traditions. This may have stimulated an even more dogmatic adherence to Honda’s Way-the single-crank concept.

But Honda would stand GP racing on its head with the brilliant Big Bang concept. The idea wasn’t a new one. Suzuki tried it in the late 1970s, but emphasis was on static testing, rather than dynamic testing, so the benefit remained hidden.

Later, in the mid-’80s, Cagiva had the same idea, and came up with its Bombardone (Big Bang) squareFour motor. Testers reveled in the controllable sliding the revised engine configuration delivered, but there was a problem. In those days, all GP races began with push-starts. With all four cylinders firing closely together, the rider couldn’t bump-start the engine unaided. So the idea was dropped.

It was picked up by HRC, ravenous for a world championship in 1992. As Suzuki found out earlier, the dyno would show no difference between Big Bang and conventional engine, for how can one cylinder know what the others are doing? Yet acceleration was improved as test riders, able to sense sliding again, instinctively rode closer-safely-to the limit.

A rider’s security lies in adhering to what works for him. Doohan, able to ride the violent NSR500 as it was, was at first skeptical, and it would take several test days before he was persuaded of the Big Bang engine’s value. Freddie Spencer, who rode the new NSR in South Africa at a post-season test session, likened its seemingly dull, lackluster delivery to the deceptive way an RC30’s flat torque gathers speed. Spencer says the Banger is much easier to ride to 98 percent, but very difficult to take to its outer limit.

With it, Doohan crushed all opposition, winning the first GPs of 1992 four straight, building up enormous leads. Had he not been subsequently sidelined with a badly broken leg, Doohan would have needed only a few more points here and there to be sure of the championship. Yamaha, forced suddenly into an inferior position, responded by building-in more top speed at the expense of smooth acceleration. Rainey, faced with an out-of-balance machine, began uncharacteristically to crash. Nevertheless, Rainey forged ahead in points-as Doohan recuperated-to win his third championship in a row.

Honda management’s stubborn attachment to the single crank had been strong enough to make its engineers truly desperate, willing to gamble on something very different-even crazy-and it had worked. But while management basked in Doohan’s early success, the twincrank opposition-now including Cagiva-were carefully analyzing the NSR’s unique droning sound signature to build their own copies. Suzuki’s Banger reportedly fires its cylinder pairs 15 degrees apart. Cagiva’s is said to fire its two pairs 66 degrees apart. It worked well enough to give that company its first-ever GP win in late ’92. Yamaha threw together a makeshift Big Bang motor for the end of the season, but will have a much-refined version at the end of its test schedule by the time you read this.

What will happen in ’93? With its monopoly on the Big Bang Theory broken, will Honda fall back into its former inferior position-having the only single-crank machine in GP racing? That would put the future NSR back with past NSRs, as a slow direction-changer relative to the opposition, fast only in a straight line. Will management continue to shackle its creative engineers to unworkable concepts? Or will they remember the founder’s frequent reminder that failure is a lesson from which to learn?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

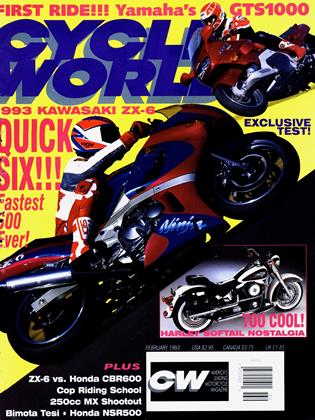

Up Front

Up FrontOr Best Offer

February 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Ducks of Autumn

February 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCComputers Vs. Intuition

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars Continue

February 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupOxygenated Fuel And the Motorcyclist

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron