Clipboard

Superbike update

There are six brands in the running in AMA Superbike, which is grand. Unfortunately, only three of them-Ducati, Honda and Kawasaki-are steadily competitive. Of the others, Harley-Davidson can afford success but chooses not to seek it very hard. Suzuki is struggling with a paradigm shift, still building a style of race engine that went out a decade ago. And Yamaha-no one’s quite sure just what Yamaha is doing.

Harley is doing some real engineering now-including the six-speed gearbox, Lighter pistons and other innovations thown at Daytona-but more horsepower

shows up on the dyno than on the track. Average Superbike engines, Team Manager Steve Scheibe says, are now making horsepower in the mid-150s at the gearbox input shaft, and there is at least one engine making significantly more.

In early practice at Loudon, New Hampshire, the Harleys were near the top, but got left behind later.

One progress marker is that independent Harley tuner Don Tilley has come to terms with the VR’s computer engine control and fuel-injection system. Another is that better reciprocating parts now allow the engines to rev as high as 12,200 rpm.

How much is enough power? Muzzy says the best Superbike numbers are closing in on 170 bhp at the crankshaft, which could explain why Harley shows promise but hasn’t yet delivered; the >

others just keep getting better!

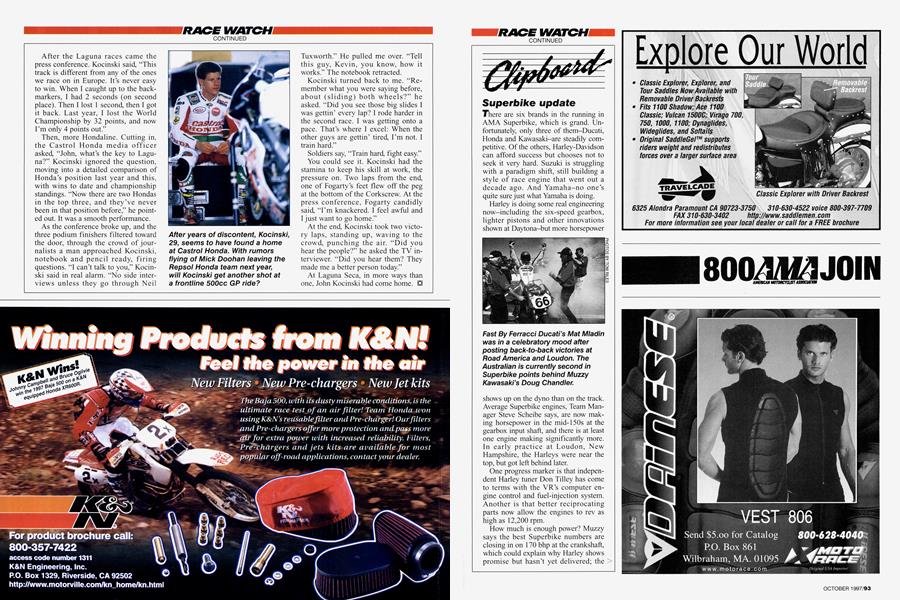

Eraldo Ferracci, the man who showed Ducati that its 851 was more than just another loud, red prototype, again has a race-winning rider in Aussie Mat Mladin. I hear tantalizing whispers of an all-new Ducati in three years, with a 60-degree V-Twin positioned farther forward, and with geardriven cams, but the pace of this development is slow, even with the capital provided by the recent buy-out. For the moment, the perfection of Ducati’s legendary compromise among handling, acceleration and speed is flawed. (Now what’s the problem, too much reliability?) This shows that it’s possible to have a great combination, and yet not quite know why it works.

Despite this, Mladin won at Foudon almost casually, saying afterward that he “never really felt comfortable on the bike.” Ferracci’s pit buzzed with exotic creatures from the NYC fashion scene, a side-effect of his DKNYmen clothing sponsorship. But Eraldo is unflappable.

Doug Chandler, his Kawasaki on a too-hard tire, quickly gave up any thought of following his hot qualifying

with a win, and ended a conservative fourth. Chandler is a careful, craftsman-like rider who does a lot of his racing before the event.

And what about Vance & Hines, the other Ducati team? After getting a late start to the season, the team has been hampered by mechanical problems, but rider Thomas Stevens managed a seventh-place finish at Brainerd, Minnesota.

Suzuki has come up in the world-at least partly through the help of rider Aaron Yates, who managed to push one of the still-peaky GSX-Rs into second at Foudon, burning up his rear tire in the process, as the laws of physics require. Yoshimura has always seemed to take the attitude, “Give us what lies above 12,000 rpm and you can have the rest.” When existing riders express consternation over the sudden power onset and languid bottom-end acceleration, the team answer has always been (in my imagination, at least), “Do something! Call John Ulrich, call Cliff Nobles! They’ve gotta know some hot kid who can ride this thing. Then, we’ll be back on top like in 1988!”

Folks are saying that Yates is being “heavily courted by Honda,” likely because they reason that, if he can ride the Suzuki this well, he could probably ride the equally difficult Honda. Still, many experienced observers remain puzzled over how a bike can include so many of the right things, and still not quite “git it.” And by now, we’ve all heard the rumor that there will be two Suzuki teams next year-a GSX-R team and a TF1000 Twin team. Yes, please!

Yoshimura has employed suspension >

consultant Dale Rathwell, and Suzuki Mission Control has finally agreed to try his ideas. Dale’s role has been to pollinate team after team with the best current thinking, but even with a suspension setup comparable to the best currently used in Superbike racing, the Suzuki powerband remains a problem.

Honda, whose RC30 began as a torquer, returns constantly to the theme of acceleration in the RC45. Kawasaki, although currently down on power, still achieves smooth, strong drives off corners, thanks to effective hook-up and good steering. Early acceleration works better than top speed to chop lap times. The proven way to success in Superbike is to build a fast tractor, which is what the top bikes are.

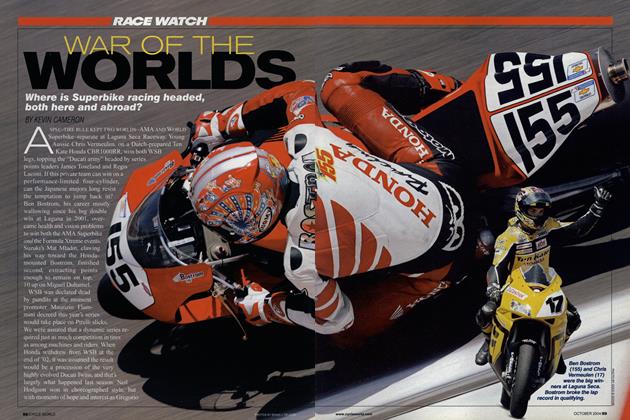

Likely a legacy of the oval-piston NR500 program, Honda’s V-Four is an engine package with drawbacks. The RC30 raced on while the company moved toward a successor in fits and starts. When the RC45 did arrive, it was later than planned, still needed development and it was no easier to ride than its predecessor. Its engine is high, and its weight is to the rear as compared with the inline-Fours. It’s a difficult bike to ride well. Steve Crevier would put his third at Loudon, but Miguel Duhamel crashed out.

I suspect, but no one will confirm, that Honda’s new craze for relaxed chassis stiffness has affected its Superbike. Good or bad? Team Manager Gary Mathers says only that the bikes “look a little easier to slide smoothly” now. Duhamel, usually a man ready with a light remark, looked terribly serious at Loudon. How would you like it if engineers half a world away made your former title-winning bike into a rubber band? Say it isn’t so!

Last year, one or two Superbikes showed light under their back tires as they braked for Loudon’s Turn 3, the slow uphill right-hander. This year, many more were doing it. Why? I posed this question to Gary Gallagher of EBC Brakes. “Sintered pads,” he said instantly and cheerfully. He went on to explain that such pads, made mainly of sintered copper powder and carbon, have some useful properties. Conventional organic pads fade at some temperature, but copper essentially does not. Organic pads are natural insulators, so nearly all brake heat goes into the discs. They respond with the usual range of symptoms, such as rapid wear and cracking. Sintered >

metallic pads share the heat load because they conduct heat well, allowing heavier brake use. Several makers, Gallagher pointed out, are supplying such racing pads now.

Yamaha gives the impression of being a company without a racing policy. The team ran one lonesome rider, Tom Kipp, at Loudon, and he finished fifth. Backing him was the giant transporter and a cast of thousands. This seems odd. Is a new bike coming? Is a new policy coming? Or is it the typical Yamaha season profile: maximum factory effort at Day-

tona with a bike that only works at that track, followed by a “you bought it, it’s yours” support policy for the U.S. team in the rest of the AMA series. Do corporate planners ever turn the telescope around to see what their operations look like from outside?

Everyone’s still at the party, but the pits looked strangely thin at Loudon. The AMA’s current strategy is to stack its chips on factory racing, and it has worked well, but now the viewer wonders if there is another option at the top level. I hope we don’t have to explore that question soon. -Kevin Cameron

Dirt-track's changing future

Recently, we got a look at the AMA’s Five-Year Plan for Dirt-Track. It calls for a gradual transition from 750cc, twin-cylinder, race-only engines to production-based lOOOcc Twins. Because this raised so many questions in my mind, I decided to call Ed Youngblood, president of the AMA, who delayed his own dinner considerably in explaining the plan and its origins.

The need for such a plan, he stated, arises for multiple reasons. First, “It’s hell for a young rider to find an XR (the veteran 750cc race engine from Harley-Davidson, currently making in

the vicinity of 100 horsepower).”

Combine this with the fact that Harley is now supplying parts sufficient only to make up for attrition, while Honda’s RS750 parts pricing indicates that neither company really wants to carry total responsibility for dirt-track into the next century. Of current dirt-track starting fields, Youngblood said, “Fifty bikes show up now, and it cannot possibly get any larger.”

That means finding a new source of engines. Speaking of the present production-based 883 class, Youngblood remarked, “When they began, people believed that serial production engines would bring cheap racing. No way! It’s expensive-in a spec class-to stay spec.” Nevertheless, he continued, “That’s been an excellent experiment,” because it showed that production engines can be used for dirt-track racing.

The other force behind the plan is the changed nature of entertainment in America. “These shows aren’t in a vacuum, but have many competitors,” Youngblood noted. That means television, which in turn means better venues (possibly on paved ovals), and tighter scheduling.

Therefore, the three real prongs of this plan are as follows: 1) to find a

way to race with production-based engines; 2) to pry dirt-track out of its traditional local and rider-centered outlook, and reconfigure it as entertainment, as has been done so well and successfully with Supercross. In turn, that means focusing on the needs of television. “There can be no more five-minute delays so someone who got bumped in the heat can change handlebars,” Youngblood explained; 3) >

to make dirt-track more attractive to beginning riders, and to provide useful incentives for riders to stay with the program. This may mean returning to a three-tier Novice/Junior/Expert format, letting economics decide equipment questions, and enhancing the status of dirt-track.

Of the equipment decisions, Youngblood said, “I’d be surprised if it happened in as little as two years.” Some teams have already volunteered to build prototype bikes for evaluation, but the full five years of the plan will be needed to allow teams to amortize existing equipment, to start Juniors on the new equipment, and to reach a working consensus among the promoters, teams, the AMA and the entertainment industry.

Can a modern lOOOcc Twin, with a proven potential for 170 crankshaft horsepower, find grip anywhere, at any speed, on dirt? “We’re going to go in a completely different direction in getting a relationship between engine and track,” Youngblood said. “Special tires

(as used now) equal groove racing. Our hope is the DOT (street) tire. Above X horsepower, more power will be unusable. Instead of trying to get more power, tuners will be detuning to get the best match-up of tire and engine. That’s pretty theoretical, but some team owners seem to like the idea-to take development in a new direction.” This is an ambitious plan, with some interesting new thinking behind it, but selling it to all those it touches will be as complex as nuclear disarmament. In the entertainment biz, nothing is for nothing-even powerful NASCAR had to buy its way onto TV This is the big question: Shall dirt-track racing just continue as a quaint, fading hold-over from America’s rural past? Or can it, like Supercross, come in from the cornfield and carve its own territory on television? Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

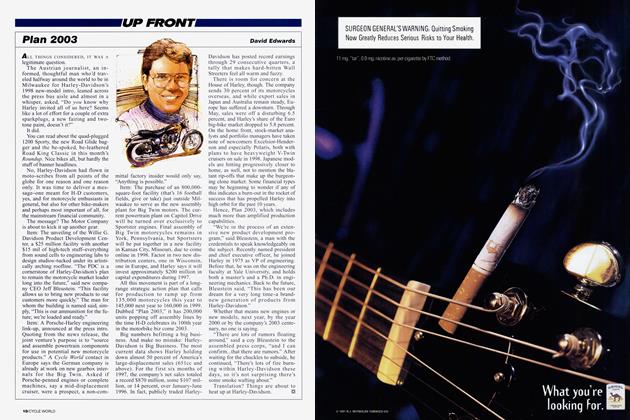

Up Front

Up FrontPlan 2003

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

Roundup

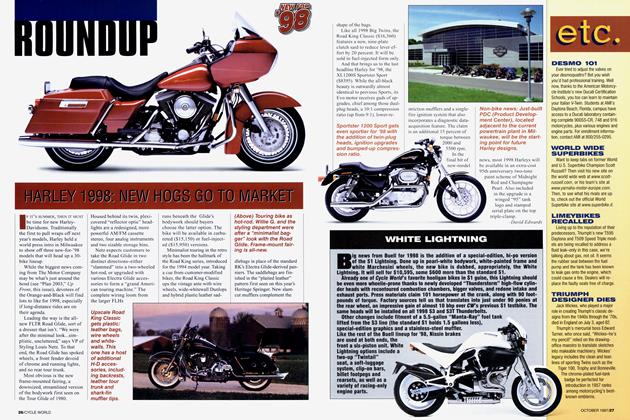

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

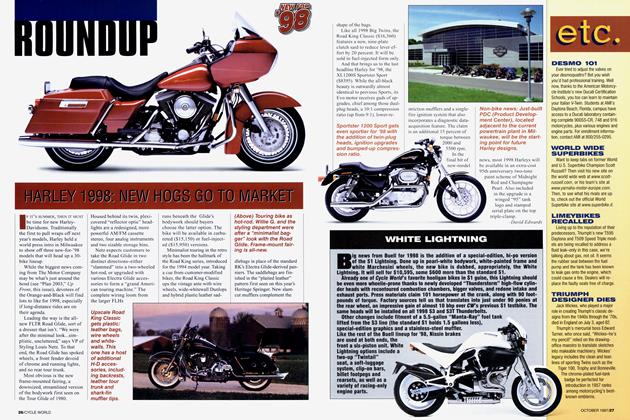

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997