Letters from the World

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

WHILE UNPACKING THE LAST OF OUR moving containers a few weeks ago, I found an old saltine cracker box made of tin. filled with letters sent to me while I was in Vietnam, 29 years ago. They were addressed to a Sp/4 Egan, MAC V Advisory Team 45, Phan Rang, APO San Francisco, Cal. 96381. Naturally. I stopped unpacking and started re-reading the mail, most of which I hadn’t looked at since the day it was first opened.

One of the letters was from mv old

college friend, Todd Saalman, who was still attending the University of Wisconsin the year after 1 quit and joined the Army. Todd wrote funny, bleak, scatological.' stream-of-consciousness letters—which almost everyone did at that time—full of disorder, uncertainty about the future and unpleasant references to Nixon and Agnew. He also mentioned motorcycles in his letters.

Todd was an artist and early computer whiz who could play guitar and sing just like Paul Simon, and he bought the first Suzuki X-6 Hustler 1 ever saw. He brought it back to the dorms one day and did a smoky burnout the entire length of the first-floor hallway as we all stood safely back in our doorways and watched. He flew through the open doors of Sullivan Hall at a high rate of speed with the David-Crosby-like cape he was wearing fluttering behind him, leaving the hailway filled with acrid two-stroke haze. The handlebar ends cleared the doorway by inches, and everyone was quite impressed with his fearlessness.

This was the sort of thing people did in the Sixties when they were bored, and it probably explains a lot about our involvement in Vietnam. Excessive flamboyance and energy in all things, even self-destruction, was the disease of the decade.

Anyway, Todd would occasionally write me letters while I was stationed in what was then called The Armpit of the World. In retrospect, it was actually quite a beautiful country, a place whose reputation as a vacation spot was somewhat damaged by the stigma of death that clung to its green mountains and rice paddies like so much heavy fog. But back then, we enjoyed calling it The Armpit of the World and sat on sandbags reading our letters from home.

And there I was, in 1969. sitting on

my particular sandbag, reading Todd's letter. It rambled on about the usual campus happenings, co-op living problems, politics and so on, but it ended with a rather key passage. In closing, he said, “Me and a bunch of crazies rode our bikes out to the Mississippi Cliffs last weekend and camped at Wyalusing .State Park. Beautiful cold autumn night, huge campfire, guitars, etc. Stayed up all night. Wish you were there. Or here. Or somewhere else. Anywhere.”

I could picture firelight reflecting off the spokes and pipes of the gathered motorcycles, see my sleeping bag laid out on the ground near the fire. And then there would be friends around, people with whom you shared beliefs, to talk and drink and smoke with. And girls.

Good Lord, girls. We didn't call them women then. Women were an older species who wore severe business suits and stamped your student registration card with a menopausal vengeance. Women who went on dates and rode motorcycles and camped out were called girls. Even now, it sounds friendlier. We were the boys and they were the girls.

What I felt most of all in Todd's letter, however, were the usual bohemian freedoms we all treasured so much. The freedom to own a sleeping bag of some color other than olive drab, to hike unarmed, to stay up all night or sleep all night, to get up when you pleased, to choose your friends and let them choose you. Most of all, the freedom to get on a bike and go. That was the key.

I don’t think I've ever had a mo-

ment where the image of personal freedom was as clearly etched in my mind as it was during the few minutes of reflection I spent with Todd's letter. The whole nighttime autumn camping scene was complete in my imagination, right down to the last detail, like the persistent memory of a landscape seen in a lightning flash. Or a tripflare.

What I also understood, aruds-

ingly, was that without the Army and its tiresome discipline, without the vast distance separating me from the Mississippi Valley, there would have been no vision at all. It was pure contrast that made Todd's weekend ride seem larger than life.

But it did loom large, and it's possible I remember that camping trip better than the people who were on it. I probably had more fun that night than anybody, and I wasn't even there. I was in two places at once, while they were only in one.

Sometimes, however, one is just the right number of places to be. Like last weekend. Barb and I woke up and discovered it was a beautiful golden late-autumn morning, a throwback to the previous month's sunniness and warmth. Indian fall, if not exactly Indian summer.

“Let’s load up the Beemer and go camping.” I said. “It's probably our last chance of the year.”

“Where do you want to go?” Barb asked.

“Wyalusing,” I said.

We got out our sleeping bags and tent, packed up and headed southeast toward the river. Our friends Chris and Dana joined us on their reconstituted $750 Gold Wing, and by sundown we were camped on the cliffs above the mighty Father of the Waters.

It was a cool, rustling autumn night with a diamond-black sky and a million stars, and we built a great big campfire, around which we stood, talking and drinking Jack Daniel’s. Firelight reflected off the spokes and pipes of our bikes, and the fire warmed our faces and hands.

It was a very good evening for me, and I drank a silent toast to Todd and his fine letter. And to the little-appreciated, nearly always motorcycle-related luxury of being in just one place at a time, and not wishing to be anywhere else. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAscot Eulogy

February 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeDoin' the Norton Rap

February 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1991 -

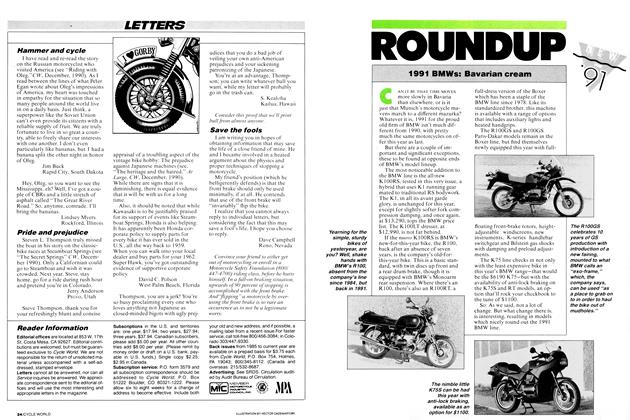

Roundup

Roundup1991 Bmws: Bavarian Cream

February 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupCzeching Out Jawa

February 1991 By Pavel Husák -

Roundup

RoundupNew Frames For Old Art

February 1991 By Alan Catheart