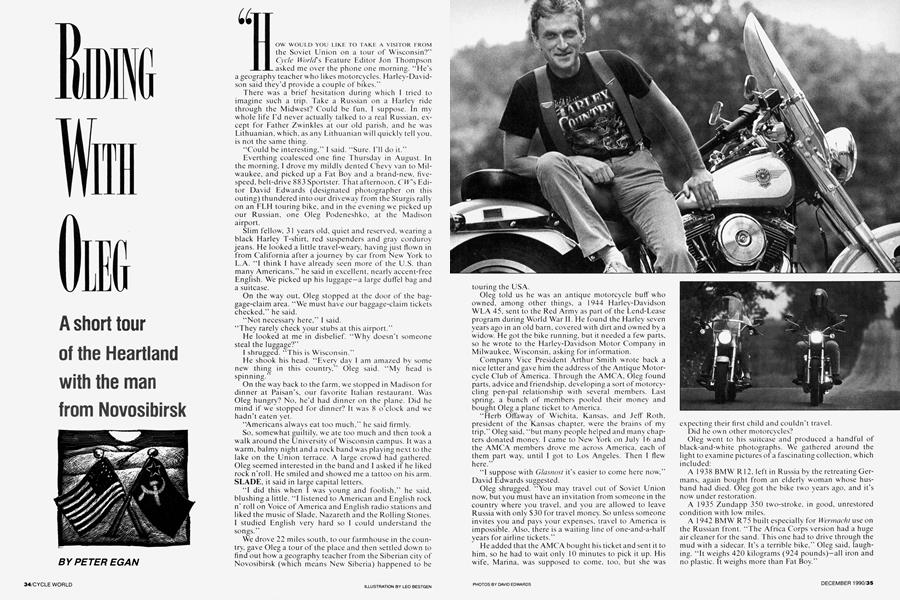

RIDING WITH OLEG

A short tour of the Heartland with the man from Novosibirsk

PETER EGAN

"HOW WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE A VISITOR FROM the Soviet Union on a tour of Wisconsin?" Cycle World's Feature Editor Jon Thompson asked me over the phone one morning. "He's a geography teacher who likes motorcycles. Harley-Davidson said they'd provide a couple of bikes."

There was a brief hesitation during which I tried to imagine such a trip. Take a Russian on a Harley ride through the Midwest? Could be fun, I suppose. ín my whole life I’d never actually talked to a real Russian, except for Father Zwinkles at our old parish, and he was Lithuanian, w hich, as any Lithuanian will quickly tell you, is not the same thing.

“Could be interesting,” I said. “Sure. I'll do it.”

Everthing coalesced one fine Thursday in August. In the morning, I drove my mildly dented Chevy van to Milwaukee, and picked up a Fat Boy and a brand-new, fivespeed, belt-drive 883 Sportster. That afternoon, CW's Editor David Edwards (designated photographer on this outing) thundered into our driveway from the Sturgis rally on an FLH touring bike, and in the evening we picked up our Russian, one Oleg Podeneshko, at the Madison airport.

Slim fellow, 3 1 years old. quiet and reserved, wearing a black Harley T-shirt, red suspenders and gray corduroy jeans. He looked a little travel-weary, having just flown in from California after a journey by car from New York to L.A. “I think I have already seen more of the U.S. than many Americans,” he said in excellent, nearly accent-free English. We picked up his luggage—a large duflel bag and a suitcase.

On the way out, Oleg stopped at the door of the baggage-claim area. “We must have our baggage-claim tickets checked,” he said.

“Not necessary here,” I said.

“They rarely check your stubs at this airport.”

He looked at me in disbelief. “Why doesn't someone steal the luggage?”

I shrugged. “This is Wisconsin.”

He shook his head. “Every day I am amazed by some new thing in this country,” Oleg said. “My head is spinning.”

On the way back to the farm, we stopped in Madison for dinner at Paisan’s, our favorite Italian restaurant. Was Oleg hungry? No, he'd had dinner on the plane. Did he mind if we stopped for dinner? It was 8 o’clock and we hadn't eaten yet.

“Americans always eat too much.” he said firmly.

So, somewhat guiltily, we ate too much and then took a walk around the University of Wisconsin campus. It was a warm, balmy night and a rock band was playing next to the lake on the Union terrace. A large crowd had gathered. Oleg seemed interested in the band and I asked if he liked rock n'roll. He smiled and showed me a tattoo on his arm. SLADE, it said in large capital letters.

“I did this when I was young and foolish.” he said, blushing a little. “I listened to American and English rock n' roll on Voice of America and English radio stations and liked the music of Slade, Nazareth and the Rolling Stones. I studied English very hard so I could understand the songs.”

We drove 22 miles south, to our farmhouse in the country, gave Oleg a tour of the place and then settled down to find out how a geography teacher from the Siberian city of Novosibirsk (which means New Siberia) happened to be touring the USA.

Oleg told us he was an antique motorcycle buff who owned, among other things, a 1944 Harley-Davidson WLA 45. sent to the Red Army as part of the Lend-Lease program during World War II. He found the Harley seven years ago in an old barn, covered with dirt and owned by a widow. He got the bike running, but it needed a few' parts, so he wrote to the Harley-Davidson Motor Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, asking for information.

Company Vice President Arthur Smith wrote back a nice letter and gave him the address of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America. T hrough the AMCA, Oleg found parts, advice and friendship, developing a sort of motorcycling pen-pal relationship with several members. Last spring, a bunch of members pooled their money and bought Oleg a plane ticket to America.

“Herb Offaway of Wichita, Kansas, and Jeff Roth, president of the Kansas chapter, were the brains of my trip,” Oleg said, “but many people helped and many chapters donated money. I came to New York on July 16 and the AMCA members drove me across America, each of them part way, until I got to Los Angeles. Then I flew here.”

“I suppose with Glasnost it’s easier to come here now,” David Edwards suggested.

Oleg shrugged. “You may travel out of Soviet Union now, but you must have an invitation from someone in the country where you travel, and you are allowed to leave Russia with only $30 for travel money. So unless someone invites you and pays your expenses, travel to America is impossible. Also, there is a waiting line of one-and-a-half years for airline tickets.”

He added that the AMCA bought his ticket and sent it to him, so he had to wait only 10 minutes to pick it up. His wife, Marina, was supposed to come, too, but she w;as expecting their first child and couldn't travel.

Did he own other motorcycles?

Oleg went to his suitcase and produced a handful of black-and-white photographs. We gathered around the light to examine pictures of a fascinating collection, which included:

A 1 938 BMW R 1 2. left in Russia by the retreating Germans. again bought from an elderly woman whose husband had died. C)leg got the bike two years ago, and it’s now' under restoration.

A 1935 Zundapp 350 two-stroke, in good, unrestored condition with low miles.

A 1 942 BMW R75 built especially for Wermacht use on the Russian front. “The Africa Corps version had a huge air cleaner for the sand. This one had to drive through the mud with a sidecar. It’s a terrible bike,” Oleg said, laughing. “It weighs 420 kilograms (924 pounds)—all iron and no plastic. It weighs more than Fat Boy.”

A 1948 BMW R35. a vertical 350 Single, found in a barn, but this time owned by an old man who could no longer ride. It had a loose flywheel and needed a new piston, rings and rod bearings. The bike has just been reassembled after a four-year restoration.

Last and perhaps weirdest, a composite motorcycle that looked something like a praying mantis, a dual-purpose, cross-country bike Oleg fabricated from pieces of three or four relatively modern Eastern Bloc two-strokes after seeing pictures of enduro bikes in old American magazines. It had an engine from a 250 Serial (a Russian brand Eve never heard of ). f rame f rom another Serial, extended forks from an Ish (Russia's oldest motorcycle manufacturer), cylinder head from a CZ. and a Mikuni carb.

Oleg rode this bike w ith “no trouble” from Novosibirsk to Moscow' and back a few’ years ago, a four-week round trip of 4800 miles. He cooked most of his meals along the road and camped in a tent, or sometimes “made a tunnel in a haystack” and slept there.

He told us the Harley 45 is his everyday bike and he rides it a lot. “When you write the story,” he said, “I want you to say that the old people of Russia who remember World War II like to see this bike and they appreciate it very much.”

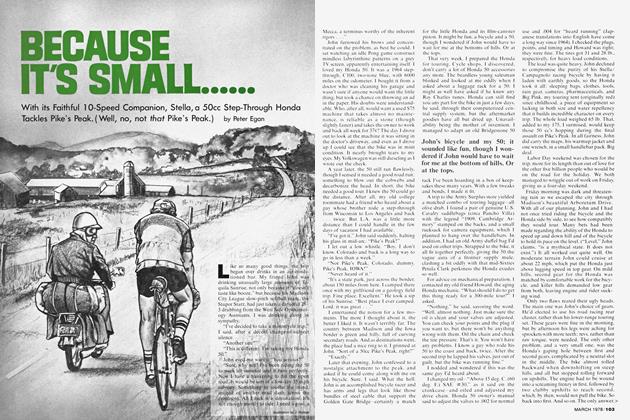

In the morning, we got up early to traveled on three slightly newer Harleys. Though we’d intended the Fat Boy for Oleg, he thought the smaller Sportster would be a better bike for him to start out on, so I rode the Fat Boy and David the FLH. We struck out toward the Mississippi on the empty, gently curving, up-and-down country roads of southwestern Wisconsin into a beautiful summer day.

Oleg rode slowly and tentatively at first, swinging wide on several of the corners, but then he seemed to get the hang of the Sportster and picked up the pace, cornering smoothly. We stopped for breakfast at the Red Rooster Café in the historic Welsh mining town of Mineral Point, and Oleg pronounced the roads “unbelievable” and the Sportster “fantastic.”

He had never ridden a motorcycle with so much speed and horsepower, he told us. Most Russian bikes were small-bore two-strokes and had to be ridden flat-out to go 50 or 55 mph. “The Harley has unbelievable horsepower,” he said, shaking his head. “You just turn the throttle and it goes.”

Roads in Russia, he added, tend to have a lot of potholes and stones, except around the large cities, so you seldom ride faster than about 35 mph. There was nothing to compare with the smooth, curving blacktop of rural Wisconsin. “Also,” he said, “I don't see any police on the road. In Russia, whenever I want to see a policeman, I can always see one.”

Beautifully said.

After breakfast, Oleg thought he was ready for the Fat Boy, so we traded bikes. I found the nimble Sportster more to my liking on these roads, but Oleg, at our first rest stop, said he much preferred the Fat Boy. He gave us a double thumbs-up and said, “This is a great bike.”

We descended a long green valley toward the Mississippi, then climbed back up to the cliffs of Wyalusing State Park for a view of the Big Muddy. The woman park ranger at the gate said we could ride through the park for free, but if we stopped to look at the view, we would have to pay $3.50 each, same as people who were camping overnight. I explained we had a guest from Russia who would like to see the Mississippi, just fora moment. “If you stop, you’ll have to pay $3.50 each,” she repeated cheerfully.

“Sorry,” I said, “$ 10.50 is too much for a view.”

So we rode through the park for free and stopped anyway. “It’s the American way,” I told David. “We can’t have Oleg thinking we obey inflexible authority. Puts democracy in a bad light.”

We took in the view (which I estimated to be worth around $3 in today's scenic-overlook market), escaped from the park unarrested and rode up the river through Prairie du Chien, stopping for lunch at a small mom-andpop café. Oleg ordered a hamburger and a glass of milk, which is also what he had ordered for breakfast.

“Do you have places like this in Russia?” David asked.

Oleg shook his head. “In America, restaurants are everywhere, but in the Soviet Union, there are not so many and they are harder to find. Here, you can find a place to eat in less than half an hour of riding. On my trip to Moscow, I could ride several days with no restaurant. I had to take food along.”

“Are the restaurants like this?” I asked.

He shook his head again. “Everyone is polite here. They always smile and say ‘please’ and ‘thank you' and ‘have a good day.’ I’ve never seen this before. In a Russian restaurant, they are more rude. They are not bad people, but I think they are just tired.”

We rode up the Mississippi for 20 miles, then turned back into the hills on Highway 82 at De Soto, curving up toward the beautiful Kickapoo River valley. We stopped to rest at the village of La Farge, and Oleg noticed that a small nut had fallen off the post for the Fat Boy’s ignitioncoil wire. So we pulled into a small engine-repair shop called Mow & Snow. Its owner, Dick Hatton, found a nut for us and installed it with Loc-tite, no charge. “Great thing about a Harley,” he said, tightening the nut, “you can fix it anywhere. It’s all blacksmith work.”

“Every day I am amazed by some new thing in this country,” Oleg said. “My head is spinning!’

Meanwhile, Oleg was wandering around the shop in a daze, smoking a Camel and looking at the chain saws, lawn mowers, snowmobiles and garden tractors. He pointed to the row of used garden tractors and said, “In Russia this is a dream. We need these tractors, but it is impossible to find one, so we make our own from some old pipes and iron and an old motor, but they don’t work.” He inhaled

deeply on his cigarette and said, almost in a whisper, “You live in paradise.”

Dick Hatton looked around at this cluttered shop and his lawn full of rusting implements, then shook his head and grinned. “Well,” he said, “this place has been called a lot of things before, but never paradise.”

By the time the Harley was fixed, a small crowd of Mow & Snow customers had gathered around Oleg and were either discussing Harleys or asking questions about Russia. Interestingly, nearly everyone at the shop had owned or worked on Harleys at some point in life and knew all about them.

As we prepared to leave, a truck driver shook Oleg’s hand vigorously and said. “I guess I’ll never get a chance to shake hands with Gorbachev, so I'll shake hands with you.”

Oleg smiled and said with mock dignity, “Shaking hands with me is same as Gorbachev.”

This produced uproarious laughter from the group. We waved goodbye and rode off.

On the way out of La Farge, we passed a scrapyard full of old cars. Oleg stopped and stared at it for several minutes. “This is amazing,” he said. “You never see this in Russia. Every car is too valuable to throw away, so they are all fixed up and kept running. Even old ones.”

“What if they are badly wrecked,” I asked, “like some of these?”

“If it is very bad, then, all the good parts are taken off immediately, because someone needs them. The car is gone.” He made a small gesture of explosion with his hands. Poof.

We rode up highway 131 past Wildcat Mountain State Park and then turned off on County Road F toward a

hilltop junction of roads called St. Marys. Here, I had booked us into a bed & breakfast place, sight unseen, called The Convent House. It was a former Catholic convent, built in 1903 adjacent to a parochial school and a beautiful old Gothic church. The Franciscan nuns had closed the convent in 1972 and the parish priest. Father Scheckel, had decided to help support the school by turning it into a bed & breakfast inn. A charming, immaculate place, run by an equally charming woman named Thelma Hughes.

On a warm, perfect summer evening. Thelma served us wine coolers on the front porch and said that Father Scheckel, an avid motorcyclist, would be pleased to see the Harleys when he returned to the nearby rectory. On Thelma’s recommendation, we later rode down the valley to the small village of Mel vina for a Friday-night fish fry at a bar/restaurant called Mel’s Running Inn. We had beers at the bar and Oleg soon had us surrounded with another crowd of curious well-wishers, who were trying out their small vocabularies of Russian words, mostly nvet, da, vodka, Khruschev and Stolichnaya.

The food was excellent, the people were friendly and the owner/cook (who introduced himself as “Baby Huey”) was a Harley buff who came out of the kitchen to see our bikes and shake hands with Oleg. The surrounding scenery was spectacular. Even Wisconsinites, accustomed to green rural beauty, call this part of the state God's Country. I put both the Convent House and Mel's Running Inn down on my mental list of repeat Destinations for future weekend bike rides.

In the morning, we had breakfast at the Convent House with Father Scheckel, a cheerful, energetic young priest who travels by KZ650 whenever possible and thinks someday he might buy a Sportster. We toured the old church and the cemetery, its headstones bearing the names of German Catholics who settled the area. We said goodbye to St. Marys and headed for home. Time to roll.

As they rode away, I found myself touched by the crazy unlikeliness of Oleg’s trip to America.

South on Highway 71 through Norwalk and Kendall, over the Ridge Road (County Road P) to my old hometown. Elroy. We were now on the familiar backroads of my wild motorcycling youth, and I led Oleg and David on a convoluted, 100-mile route down to the Wisconsin River and then back to our farm and an enchilada dinner prepared by my wife Barbara. Oleg gave his tacit approval to Mexican food by eating like an American. “Too much,” he groaned, after the damage was done.

On Sunday, as Oleg packed his bike to leave, we recorded some Rolling Stones tapes for him (a true connoisseur, he recognized Rolling Stones Now as the best of the early albums). He also ate five bananas during the morning and told us he’d had only one banana in Russia, which his mother bought him for a treat when he was 6. I tried to picture the housewives of America putting up with a supply system that allowed a 25-year banana shortage, but couldn’t. After 24 hours, some enterprising capitalist would fly them in by helicopter from South America.

We shook hands with Oleg, said goodbye and he climbed aboard the Fat Boy. He and David rolled down the driveway, headed for Milwaukee to return their bikes and take a tour of the Harley-Davidson factory. In Milwaukee, new hosts from the Antique Motorcycle Club of America would take over the last few weeks of Oleg’s visit.

As they rode away, I found myself touched by the crazy unlikeliness of Oleg’s trip to America. It counted on so many strange and wondrous threads to hold it together. His own curiosity and love of adventure; his passion for motorcycles; English learned for the sake of rock n’ roll; nights spent listening to the Voice of America; Gorbachev and the recent changes he’d wrought in the Soviet Union; the remarkable generosity of the people in the AMCA; the further generosity of Harley-Davidson for providing bikes—and for still making a bike whose soul was linked directly to an old wartime 45, given to the indomitable Russian troops by an earlier generation of Americans. A machine to help save their lives, and ours.

Writer John Barth was right, I concluded. Life is a large and intricate spider web. When you touch one part, however distant, the vibrations are felt on every strand.

I also thought it was interesting that motorcycles and rock n’ roll could be such a strong catalyst for good in the life of someone like Oleg Podeneshko from Siberia. Rock music and bikes; the two things our parents told us were no damned good.

The Peace Corps takes many forms. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue