AT LARGE

The heritage and the hatred

Steven L. Thompson

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BUY INTO A CON-

spiracy theory to suspect that there's more to the abhorrence many so-called “classic-bike” types feel for Japanese motorcycles than simple nostalgia for Old World four-strokes. You only have to peel back the cover on the anti-Japanese story a little to discover the ugly stuff: racial prejudice, resentment that a former WWII enemy buried “our” industries, and a festering suspicion that they managed to do it not with better hardware but with some dark coalition of unseen forces.

Everyone who is involved with classic machinery knows how fierce is the hatred of Oriental hardware among many Angloand Europhiles, and like most ugly prejudices, this one can't be talked away. It'll just have to die, as the closed-minded bigots who keep it alive finally themselves pass on to their rewards.

With this as the understood background noise of the classic world, it’s always a pleasant surprise to find a glimmer of light, a sign that somebody—or a lot of somebodies—sees the bigger picture. I got one of those signs at the Steamboat Springs annual motorcycle week this year. As in the last three years, there was not only the vintage roadrace day on the Mt. Werner circuit, but also a vintage trails and a vintage scrambles.

The surprise wasn't that there were a lot of over-40 guys having a great time on Hondas as well as BSAs, but that a major sponsor of the event was Kawasaki. And Kawasaki, in fact, has been a sponsor at Steamboat for some time. This showed not only shrewdness on the part of the people at Kawasaki USA, but also raised once again the issue of the classicness of Japanese bikes, and of real, as opposed to fantasy history.

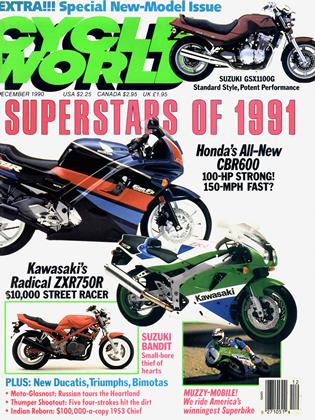

As I wandered the paddocks of the MX and roadrace events, I thought about the irony that it was Kawasaki, and not Honda or Yamaha, that was helping with sponsorship here. Although I had been one of the few who raced a factory-built Kawasaki roadracer (a '69 A1 R), the truth is that it was Yamaha that changed history with the TD series of giant-killing 250cc two-stroke GP bikes.

Honda built race kits for its street four-strokes, as well as whole bikes (such as the 50cc CR1I0 and the 125cc CR93, both jewel-like and both now almost unbelievably expensive). Suzuki sold a few “TR” factory-made blue-and-silver roadrace machines based on its own street hardware (such as the T20 and T500). Kawasaki’s “green meanies,” the 250cc A IRA, 500cc H1R and 750cc H2R, were notable more for their rarity than their ubiquity at any but major races.

The cumulative effect of all these machines was finally and completely to end the British and European era of racing dominance. Only the most lunatic of diehards believes that anything else but better engineering was the cause of that. So where. I wonder as I stroll past the old iron in the paddock, are the Japanese bikes? Scattered among the Matchlesses and Nortons are a few; a TR3 with an RD-derived engine, a TD3, a handful of 200-class CB160 and CB175derived Hondas and a fewbigger ones, such as a CB450 “Black Bomber” and the potent 1 962 CB77based 350 of Tom Marquardt.

It’s good they are here, among all the Italian and German and British hardware they obsoleted. but even as Dave Roper, rider wizard of Team Obsolete, tells me he's bought himself a Kawasaki A 1 R. I wonder again why the old machines of the Big Four are not more in evidence here, or anywhere else, including on display at corporate headquarters. Inevitably, I think of the Tale of the Crushed Hondas.

This Tale was current among magazine types and racers during the 1 970s; at its core was the rumor that Honda, rather than preserve its stunning World Championship GP machines, sent them to the crusher. As the decade unfolded, we began to hear that it was old Mr. Honda himself who’d insisted on this, but that, somewhere deep in Honda-land, the historic Sixes and Fours were kept safe and intact in spite of his dictates. Finally, the truth emerged, and it turns out to be that a staggering collection of historic Hondas of all types has indeed been saved, and is displayed in an invitation-only hall hidden under a bowling alley.

There is more to this than just Honda’s corporate culture. Most Japanese manufacturers have a “forward” view' that predisposes them to consider any non-current race machine as yesterday’s mostly worthless junk, costing time, space and money to store and care for. An artifact of the postwar expand-or-perish period of Japanese history, this phenomenon seems to have been made up of complex psychological components, which are less relevant and evident every day. One of those factors, say some observers of Japanese culture, is an ultimately self-serving desire not to “offend” foreigners by “boasting” too much.

But telling the truth is not boasting. And the truth is that the Japanese alone did not write the latest tumultuous chapter in motorcycling’s history. They provided the mechanical means by which we—the world's racers and riders—wrote it. Ours is therefore a shared heritage. And now, for a whole host of reasons, we—the riders—are working, singly and in groups, to preserve and celebrate that heritage.

The once-great Old World companies some among us glorify can no longer help us, because they're dead. But the Big Four are very much alive. And so it seems only fitting that they now look at the heritage they helped make possible as more than just past profits; it seems fitting to ask them to follow Kawasaki’s lead and support the classic scene.

They might not make much money doing that, of course. But they might make something even better: They might, at long last, make friends out of enemies. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

December 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1990 -

Roundup

Roundup$50,000 Italian Exotic

December 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars of 1991

December 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupCw 25 Years Ago December, 1965

December 1990 By Doug Toland