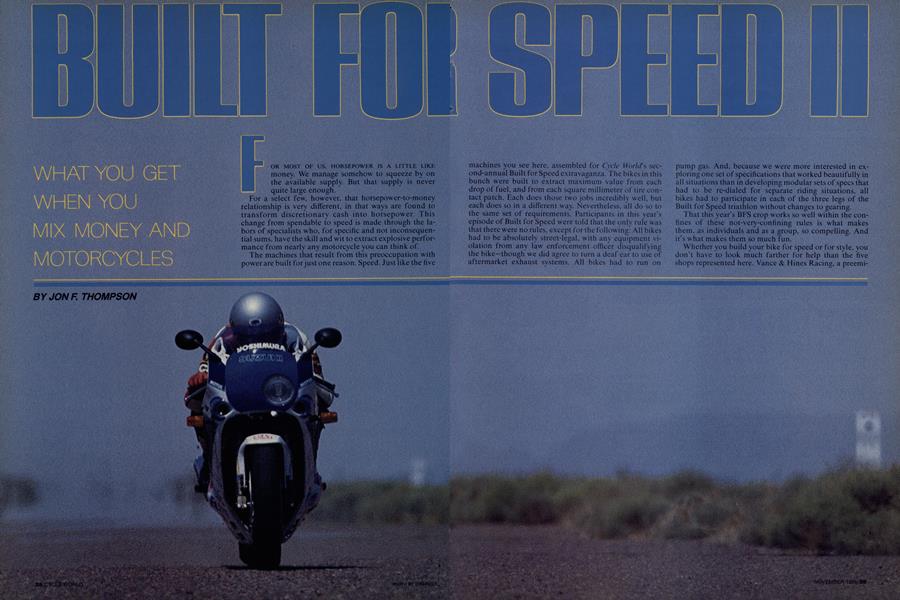

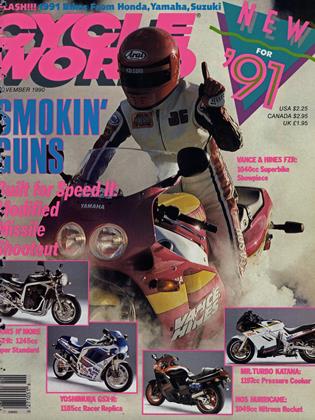

BUILT FOR SPEED II

WHAT YOU GET WHEN YOU MIX MONEY AND MOTORCYCLES

JON F. THOMPSON

FOR MOST OF US, HORSEPOWER IS A LITTLE LIKE money. We manage somehow to squeeze by on the available supply. But that supply is never quite large enough.

For a select few, however, that horsepower-to-money relationship is very different, in that ways are found to transform discretionary cash into horsepower. This change from spendable to speed is made through the labors of specialists who, for specific and not inconsequential sums, have the skill and wit to extract explosive performance from nearly any motorcycle you can think of.

The machines that result from this preoccupation with power are built for just one reason. Speed. Just like the five

machines you see here, assembled for Cycle World’s second-annual Built for Speed extravaganza. The bikes in this bunch were built to extract maximum value from each drop of fuel, and from each square millimeter of tire contact patch. Each does those two jobs incredibly well, but each does so in a different way. Nevertheless, all do so to the same set of requirements. Participants in this year’s episode of Built for Speed were told that the only rule was that there were no rules, except for the following: All bikes had to be absolutely street-legal, with any equipment violation from any law enforcement officer disqualifying the bike-though we did agree to turn a deaf ear to use of aftermarket exhaust systems. All bikes had to run on pump gas. And, because we were more interested in ex ploring one set of specifications that worked beautifully in all situations than in developing modular sets of specs that had to be re-dialed for separate riding situations, all bikes had to participate in each of the three legs of the Built for Speed triathlon without changes to gearing.

That this year’s BFS crop works so well within the confines of these not-very-confining rules is what makes them, as individuals and as a group, so compelling. And it’s what makes them so much fun.

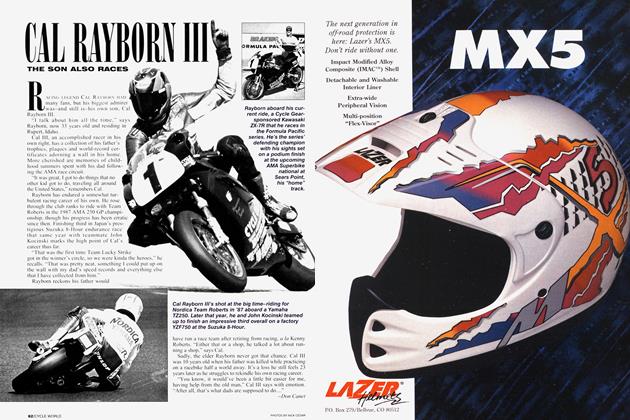

Whether you build your bike for speed or for style, you don’t have to look much farther for help than the five shops represented here. Vance & Hines Racing, a preeminent name at the dragstrips of America, these days fields a team of immaculately prepared Yamaha OWO 1 s in AMA Superbike racing. The V&H FZR1000 Built for Speed bike was finished in the same eye-popping colors as the team's racebikes, and completed the race-replica look right down to a full set of sponsorship decals. So did the Suzuki GSX-Rl 100 from Team Yoshimura, one of the most respected names in American roadracing, and a team which also fields very competitive racebikes in AMA Su perbike racing and in the WERA Formula USA series. Both the V&H FZR and the Yosh GSX-R were natu rally aspirated machines, relying on tried-and-true hot-rod techniques and very sophisticated aftermarket suspension systems to upgrade their respective performance far be yond anything possible from stockers.

Likewise a smashing little 1989 GSX-R 1100 from Fours N' More, a Reseda, California, speed shop. In addi tion to being equipped with a monster motor built to breathe "squeeze"-which is what racers call nitrous ox ide-it had also been stripped of its fairing and rebuilt into a standard-style motorcycle, complete with beautifully turned-out headlight and handlebar brackets, and footpeg mounts lowered and moved forward.

Next on hand was a 1988 Honda Hurricane 1000 built by NOS Systems. This was pretty much your basic Hurri cane, with an Ohlins shock and a warmed-over engine. Oh, and something else: Two bottles of nitrous oxide strapped onto it, along with a switch that activated the nitrous sys tem, converting the horn button to a horsepower switch.

Last, and in some ways most memorably, was a 1990 Suzuki Katana 1 100 prepared by drag-racing star Terry Kizer of Houston, Texas, through his company, Mr. Turbo, with an engine built by Jack O’Malley of Orient Express Racing. Why memorable? Well, maybe we just liked the bike’s paint job, applied by Kiser through Hired Gun, his paint shop. Or perhaps it was the fact of an estimated 230 horsepower at 13 pounds of manifold pressure-enough power to smoke the bike’s rear tire, even in fifth gear, anytime we got seriously into the boost. Whoooee!

These are motorcycles as serious as heart attacks, and that’s why we sought some serious help with them. As much fun as it is for us to roost down a dragstrip, and to search for ultimate top speeds, we’re not as quick as the pros, and when all hell breaks loose at 170 mph, perhaps not as cool-headed.

So we asked retired drag-racing star Jay Gleason to search out each bike’s top quarter-mile time for us. And we signed on Bonneville legend Don Vesco, one-time holder of the motorcycle land-speed record—he traveled 318.5 mph, is all —to reach for each bike’s top speed. Gleason would do his thing at the Carlsbad Raceway dragstrip, while Vesco would get down to business on a closed stretch of pavement deep in the California desert.

But all in good time. First, what would you do if someone unloaded five bikes like these in your driveway? Right: We went for a ride, just an innocent little overnight street ride, through some of Southern California’s curviest back-country. And we mostly behaved. Honest, occifer.

In spite of the aggressive tuning techniques applied to them, all five bikes were capable of pottering around on the street—though some were more capable than others. The Hurricane and Katana possessed the most mellow personalities of the bunch, while because the other three wore engines that had been heavily leaned upon, care had to be taken not to foul their spark plugs. The flip side, though, was that each of the three had romp-’em, stomp’em horsepower ready right now; no need to wait for the turbo, or to turn on the nitrous bottles.

Regardless of induction system, though, all five were a blast to ride. The Fours N’ More Suzuki pleased us because of its clean look, upright riding position and because its monster motor was ready to blast off anytime the throttle was cracked even a little. It displeased us because over-rich jetting caused it to load up on our mountain ride, and because mid-ride electronics problems associated with its air-shifting equipment caused the bike first to flame out completely, and then to run only when in neutral. This we sorted out in a roadside work bee.

The Hurricane won our hearts because of its straightline stability and because hitting the “squeeze” and gassing it, even in the bike’s overdrive sixth gear, was the equivalent of downshifting one notch and whacking the throttle wide-full open. We liked the Katana, once we jacked its rear preload up enough so that its exhaust ducting didn't touch down in left-handers, for its two personalities. One of them was that of the mild-mannered, deceptively fast sport-tourer the stock Katana is. But raise the manifold pressure, and the Katana became a raging beast that would peg its tach needle instantly, in any gear, all the while offering impeccable chassis behavior. All it required from its rider was nerve and the will to hang on. The V&H FZR1000 and the Yoshimura GSX-R 1 100 won our appreciation because each, with lusty engines, incredible brakes and uprated suspensions, substantially raised the standards of performance we’ve come to expect from even the hardest-edged sportbikes.

Of these five, which was our favorite on the road? In the mountains, it had to be the Yosh bike, which delivered all the usable performance any of us could want, and in addition, through its absolutely remarkable Yoshimura/ Kayaba upside-down fork, hooked us to the pavement like we’ve never been hooked before. But away from the curves, it was hard to beat the all-around usability, comfort and monster horsepower of Mr. Katana.

The Yosh Suzuki surprised us at the dragstrip, where its howling 1 185cc engine booted the bike down the quartermile in 9.77 seconds at 145.39 mph, the quickest quartermile by any of this bunch. This is especially impressive because it was done on a short, tall, wheelie-prone sports machine—absolutely the worst sort of thing for quick times at a dragstrip. That it was slower than last year’s Built for Speed best, 9.70 at 147.78, is no embarrassment, because the bike which set last year’s quick time was a Kosman Racing-built GSX-R 1100 which used an extended and hard-tailed dragbike chassis. The times and speeds of the rest of this year’s entrants looked like this: Mr. Turbo Katana, 9.86 at 1 53.06; NOS Hurricane, 9.89 at 147.78; Vance & Hines FZR, 10.10 at 143.54. By the way, note that the Katana’s phenomenal terminal speed, and realize that the bike’s e.t. is not representative of its horsepower potential. That 153-mph trap speed indicates just how much power Mr. Katana made once it began pulling hard, post-launch, against its upper gear ratios, where it could develop maximum boost.

Which leaves the Fours N’ More GSX-R. Though we had no such trouble with it on our street ride, at the strip Gleason experienced headshake so violent he was having trouble keeping his hands on the handlebar. So he parked it. Preliminary fiddling with the bike’s suspension failed to cure the problem. So the bike went back to builder John Cordona’s shop and, its chassis rechecked and a heavyduty steering damper fitted, was given another chance a week later, when it turned 9.96 at 150.75 mph. Not bad for an unfaired motorcycle.

Neither is a top speed of 168 mph, which is how fast the thing blasted past our radar gun on top-speed day. But it wasn’t easy, with the bike still shaking its head even with its new steering damper cranked down. Vesco accomplished this pass, he told us afterwards, standing on the footpegs, motocross-style. with the chin-bar of his helmet resting on the speedo in order to get all his weight over the front end. No thanks.

Top speed of the day was recorded by the NOS Honda, which ripped past our radar gun, trailing a haze of nitrous fumes, at 174 mph, a splendid improvement over the ’88 bike’s 161-mph stock top speed, but barely beating the 173 mph done in last year’s BFS by a Vance & Hinesprepared GSX-R 1 100. This year’s GSX-R 1 100, the Yosh bike, cranked off a 171 -mph top speed run; our ’90 GSXR 1 100 roadtest bike topped out at just 159 mph. The Vance & Hines FZR 1000 cranked off a top speed of 167 mph, 3 miles per hour faster than our test FZR and in no way an indication of this bike’s power—dynoed at 164 horses, compared to a stock reading of 134. The fact that the BFS II bike went no faster relates strictly to its gearing, which allows docile street behavior and killer quarter-mile times, but not the 180-mph top speeds this bike might do with different final ratios.

And finally, the Mr. Turbo Suzuki Katana blew past the CW radar gun at 164 mph. Unfortunately, “blew” is the proper word. As it reached the gun’s position on a subsequent pass, its engine expired in a huge plume of oil smoke, its head gasket but a memory. Its speed, by the way, was a full 10 mph faster than the top speed of CW*s ’90 Katana test bike, but there was some disappointment with respect to that number. As strongly as it ran on the street and at the dragstrip, we looked for 180 or better from Mr. Katana. But because of a jetting glitch, the bike never ran properly in the desert. On its last run. just before it expired. Vesco related that it accelerated hard, then slowed drastically just before the radar gun, which caught it at 161. Some potential here, we think, that went unrealized.

As for the rest, they met or exceeded their potential, with astounding acceleration and top-speeds faster than many single-engined airplanes, this in spite of the fact that gearing deliberately favored quarter-mile times at the expense of top speeds so as to not make riding the bikes in real-world situations, such as idling away from suburban stoplights, a pain in the clutch.

Now: Anyone who has been reading this magazine over the past several months will recall that our test Kawasaki ZX-11 went 176 mph, this by virtue of aerodynamics slicker than deer guts on a door knob and an engine that produces horsepower thick and rich as cream. Keep in mind that this bike, as beautifully balanced as it is, was designed by its manufacturers to post a phenomenal top speed. The trade-off is that its 10.25-second quarter-mile time, while the quickest time for any stock bike we’ve tested, was a little slower than that of the slowest Built For Speed bikes, and, in a world where a tenth-second is worth its weight in diamonds, a lot slower than that of the fastest.

So, why not just buy a ZX-1 1 and be happy with its stock performance instead of learning to love the character, charisma, and quarter-mile class of these Built-for-Speeders? Are you kidding? The question answers itself.

So we’re left with this: The current crop of Open-class sportbikes is wonderful. But with work ranging from just a little to a whole lot, each can be made so much better that their horsepower and handling begin to close in on performance levels that would have had factory roadrace pilots of just a few years ago licking their chops. None of this comes inexpensively, but when you’re looking for a bike built for speed, when a stock motorcycle is an anathema, you already know that you’re going to trade money for horsepower.

And you know, as we do, that’s a completely fair and appropriate trade.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupA Hotter Zephyr Blows Into the U.S.

November 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupResurrecting Triumph

November 1990 By Alan Cat Heart