AT LARGE

The University of Brands Hatch

Steven L. Thompson

WHEN I AWOKE IN THE FREEZING COLD Bedford van, snow falling gently but persistently, I knew at last that I was racing in England. We'd arrived at Oulton Park in Cheshire sometime around midnight, bone-weary from the five-hour drive and the 10 hours of frantic bike prep that preceded it.

It had been merely cold when we found a spot in the paddock to offload the Manx, Aermacchi and Kawasaki AIR that were the entire equipe of Thistle Racing Limited. But my English partner John Faben and I knew the BBC was forecasting some kind of serious weather. So we draped ancient canvas tarps over the bikes and crawled into sleeping bags, lying on a floor that had absorbed more Castrol R than most of the felt with which John had painstakingly lined the frame of the Manx.

The snow lay 2 inches thick on the stiff canvas when we groggily eased our aching bodies from the goosedown bags. We stood, hands thrust in anorak pockets, and watched as the other two dozen vans sprouted young men who looked as miserably as we did at the snow. Finally, John shrugged and said. “Tea, I think." And tea it was.

There was no racing at Oulton Park that first Sunday in March. 1970. But I didn't mind too much. I knew that we’d be back soon enough. And in the meanwhile, we’d be off to some other circuit. To Snetterton. Silverstone, Cadwell Park, Mallory Park, Silloth, Castle Coombe, Thruxton. Croft, Lydden or Brands Hatch. Circuits which weren’t just places for events, but which were paved classrooms, each a valuable lesson in itself for a struggling young roadracer. Individually, they were racetracks. Together, they were the University of Racing. Or, as I began to think of it, the University of Brands Hatch.

It’s hard to recall, even for a racer of my vintage, how exotic that university seemed two decades ago. It was an era of crusades, and one of them —little noticed among the wars and revolts and street fighting except by those of us who were engulfed in its fiery embrace—was the crusade by American racers to prove to the world that we were not hicks, capable only of sliding Harleys sideways.

Today, after almost a decade of American dominance on the world's grand prix tracks, such a crusade seems silly. But before Kenny Roberts stunned the GP circus with his three world titles, before Steve Baker wowed the Brits with his Yamaha TZ750. before Pat Hennen and his factory Suzuki opened Euro-eyes, Old Glory was carried Over There by privateers who fought the odds just to get on the tracks, usually unknown and unsung back in the States. Among them was me. an AFM “Expert" who quickly discovered how different were the standards of British roadracing from American.

Those standards had mostly to do with skills honed by frequent use, but they also reflected a wholly different culture of racing. In America at the time, to be a motorcycle racer was too often to be thought a freak.

Not so in Britain. The English liked motorcycle racing and even motorcycle racers. They not only showed up by the thousands in vile weather at every club event to spectate, watching with keen interest, stopwatches, red noses and meticulously filled-in race “programmes," they supported racers in the real world, too. Even a scruffy national-class racer like me got the royal treatment from almost everybody. I still keep in my files a letter from the executive director of a company called Adcola, which manufactured dual-voltage soldering irons. I’d sent a check for a couple of the irons, enclosing a note on my team stationery. In return I got them—and a check for the difference between retail and “the lowest at which we can sell these machines." As well as the director’s request that we put his stickies on the fairing, and his best wishes for a successful season, signed, “An avid motor cyclist and road-racing spectator."

Nurtured by this kind of environment. racers flourished, and the graduates of the University of Brands Hatch often went on to stellar careers in GP racing.

I wasn't one of them, but it wasn't the university's failing, it was mine. What I learned in that hard school of racing changed my life, though. I learned how to go fast by leading with my mind, not my wrist; I learned what close, frequent racing with guys you can trust means, and I learned sadness when some of them fell and did not get up. I learned patience. I learned humility—how to accept another man’s superiority in skill, and how to deal with it competitively. I learned racing and a lot more.

I’m sure these lessons were available in American roadracing; they’re universal, after all. But times were hard then for American roadracers, the tracks few, the events even fewer and far between, the chances to refine technique or hardware or even attitude still depressingly infrequent.

Which is why it’s so pleasant to contrast today’s situation. The atmosphere has completely changed in America. Granted, we still do not have the circuits per square mile that Britain boasts; but what we do have, at last, are opportunities for young Americans to enroll in their own universities of roadracing, and, more importantly, to graduate into a world of serious roadracing. So that the rest of the world wonders why we now dominate the way British once did.

To some celestial observer, there’s probably a pattern in all this. I don’t know about that. All I know is what I learned at school: Brake late, stay outside, go in hard, come out hard and never give an inch. And never, never eat a bacon sandwich at Cadwell Park.

There are worse educations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

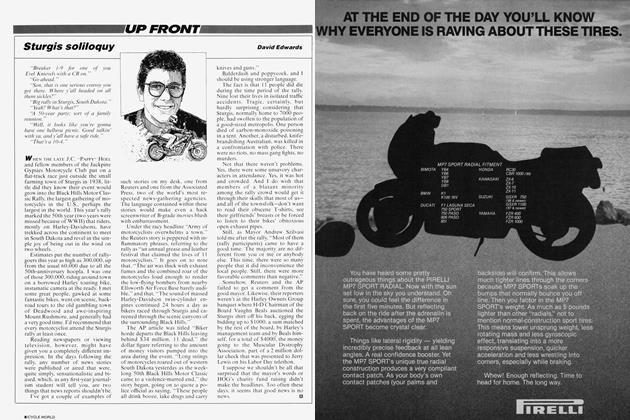

ColumnsUp Front

November 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupA Hotter Zephyr Blows Into the U.S.

November 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupResurrecting Triumph

November 1990 By Alan Cat Heart -

Roundup

RoundupCw 25 Years Ago November, 1965

November 1990 By Ron Griewe